- Summer 2023

- Who’s on first? When convention fails in the criminal trial process

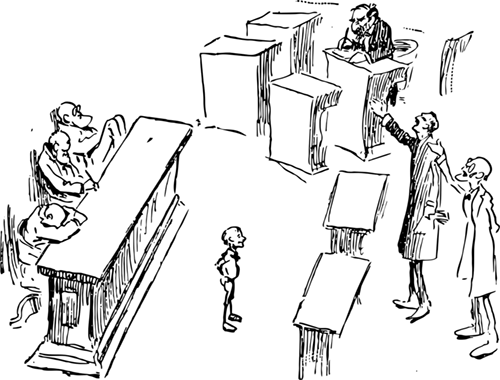

Who’s on first? When convention fails in the criminal trial process

R v Cranston (No.19) [2022] NSWSC 1580

In a multi-accused criminal trial, the convention in New South Wales is that the cross-examination of witnesses occurs ‘down the indictment’ and defence Counsel’s address to the jury ‘up the indictment’. This fairly uncontroversial approach works well when everyone agrees, but in R v Cranston (No.19) [2022] NSWSC 1580 Payne JA was confronted with a situation where the parties did not wish to follow that approach when it came to closing addresses.

To put R v Cranston (No.19) in context, it was one of 40 judgments written by Payne JA over the course of three years in a Commonwealth prosecution arising from the now infamous Plutus Payroll business. Pre-trial arguments occurred throughout 2020, 2021 and 2022 before the trial itself began in April 2023.

The five offenders had been charged under the Criminal Code 1995 (Cth) for dishonestly obtaining a benefit from the Commonwealth (specifically, something in the order of $105,000,000 in unpaid tax) and dealing with in excess of $1,000,000 as the proceeds of crime. His Honour’s 40 judgments covered everything from a separate trial application, the admissibility of evidence, the sentencing of co-offenders and ultimately the sentencing of the five accused involved in the trial from which the judgment of Cranston (No.19) emerged.

The order in which the parties were listed on the indictment was alphabetical and did not in any sense reflect a ranking of liability. By the time there was any consideration of the parties’ closing addresses, the trial had already been underway for seven months (not including the pre-trial hearings), with the parties cross-examining ‘down the indictment’. However, both defence counsel and his Honour could see that the usual convention on addressing ‘up the indictment’ would not be appropriate given the different defences each accused was running, the length of time each counsel estimated they would be addressing and the possibility of one party, inadvertently, impugning another accused who may not be able to respond, depending on when they addressed.

The convention was abandoned, but as three accused wished to address last, there was no agreement as to a suitable order, hence Payne JA was required to determine the order and provide reasons for doing so. This was no easy task because, as his Honour observed at [6] of the judgment, there is no statutory guidance about the order of addresses, with s 160 of the Criminal Procedure Act merely making it clear that the defence has a right to address, nor any binding common law authority in New South Wales.

In reaching his conclusion his Honour considered Archbold’s Pleading, Evidence and Practice in Criminal Cases published between 1862 and 1966 which referred to a practice now abandoned, that the order of final addresses be determined by order of seniority at the Bar, with the most senior going first, or by indictment order, from top to bottom. Archbold’s history of the practice changed to the point that by 1905, in the absence of agreement between counsel, the indictment order approach was adopted. However, while the cases cited in Archbold supported that rule, they were silent on the question of whether the ‘indictment order’ should be used even in circumstances where it could produce unfairness, which was an issue in R v Cranston (No.19).

His Honour considered more recent editions of Archbold as well as the United Kingdom’s Criminal Law Revision Committee, Fourth Report: Order of Closing Speeches paper, the current rules in England and Wales set out in their Criminal Procedure Rules 2020 (UK) and a series of older cases, specifically, R v Barber (1844) 1 Car & K 434, Fletcher (Public Officer) v Crosbie (1842) 2 M & Rob 417, R v Meadows* [1856] 2 Jur NS 718, R v Antill and Brown (1863) 2 SCR (NSW) 50, R v Orton [1922] VLR 469 and more recently (relatively) R v Webb and Hay (1992) 64 A Crim R 38.

At [15] and [16], his Honour stated:

I have concluded that the indictment order (or the reverse indictment order) of addresses must give way to whatever the Court considers just in the circumstances of the individual case. There is no rule applying to the order of defence addresses in a multiaccused case. Ultimately, the Court has an inherent power to organise itself and the conduct of a trial in the manner it sees fit. If the Court considers that the fairest way to proceed is to structure the defence addresses in a particular order, then it could, and should, do so.

The order of defence addresses, if no agreement has been reached, involves the exercise of a discretion by me, to be exercised judicially, to try and ensure fairness between the various accused. No a priori rule based on place in the indictment will necessarily ensure fairness in a particular case and I do not propose to adopt any such approach. I have concluded that I should require defence counsel to present their closing addresses to the jury in the order which, having regard to the way the evidence and the case has unfolded, will be fair and do justice to all parties in the case.

His Honour then listed the order of defence address with those parameters in mind. His Honour considered the nature of the respective cases, the potential lengths of the addresses, and the fact that one accused had given evidence. Critically, his Honour also identified the potential unfairness to some accused should the parties likely to deliver the shortest addresses (measured in hours, not days) be expected to address before those who were likely to give longer and more complex closing addresses, with the risk of the shorter addresses simply being lost by the jury. His Honour was also concerned that the longest address may inadvertently impugn other accused, and if that address went after the others, those other accused would not have a right of reply: at [18] and [19].

The case is extremely useful because it not only deals with an issue which will certainly arise again. It illustrates that in circumstances where following the convention of ‘addressing up the indictment’ may not be appropriate, it does not need to be followed.

Secondly, the case provides both the court and practitioners with considerations that should be taken into account in setting the ‘batting order’ when the parties cannot reach a consensus themselves. As his Honour makes clear, the overriding concern of the court is what order is most likely to ensure fairness to all parties. BN