- Winter 2023

- Yes Minister, you must exercise your intervention power personally: Davis v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs & Ors [2023] HCA 10

Yes Minister, you must exercise your intervention power personally: Davis v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs & Ors [2023] HCA 10

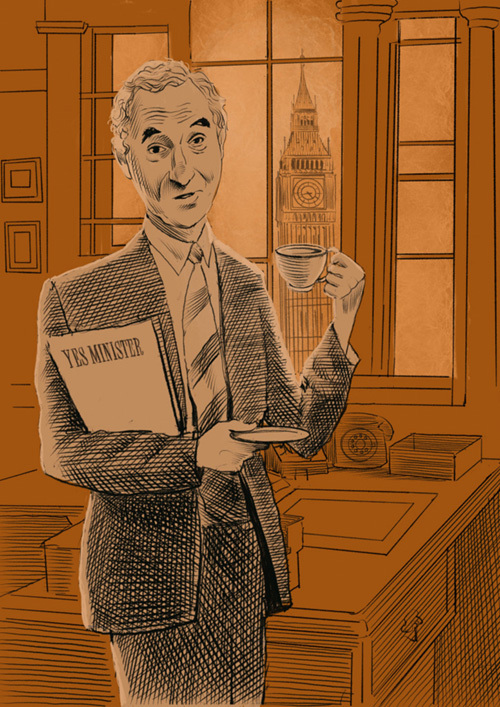

Davis comprises five separate judgments, references Yes Minister’s master of obfuscation, Sir Humphrey Appleby, and is sure to have a significant impact upon the Department of Home Affairs’ handling of requests for ministerial intervention.

The High Court, by majority, upheld two appeals and found that the Minister’s power under s 351 of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) to intervene and substitute a more favourable decision must be exercised by the Minister personally. The decisions of departmental officers to not refer requests for ministerial intervention to the Minister, made pursuant to guidelines issued by the Minister, were therefore invalid.

The ‘very large question’ of whether any aspect of the executive power of the Commonwealth is conditioned by any requirement of reasonableness was identified but not decided.

Background

The appellants had resided in Australia for over 25 years and around 30 years respectively. Having failed in their respective partner and protection visa applications, they requested the Minister exercise the power under s 351(1) of the Act and intervene in their cases. Section 351(1) gives the Minister a non-compellable personal power to override an administrative decision and substitute a decision that is more favourable to an applicant if the Minister ‘thinks that it is in the public interest to do so’. Due to the non-compellable nature of the provision, the Minister does not have a duty to use, or even to consider, using the power.

In practice, requests for Ministerial intervention are made by writing to the Minister with an explanation of why a case is unique or exceptional to warrant intervention. The appellants’ requests were not referred to the Minister. Instead, they were finalised and refused by the department because they did not meet the guidelines that the Minister had issued on ministerial powers. The guidelines instructed the departmental officers how to deal with requests for the Minister’s intervention under s 351 of the Act, including how to identify requests that the Minister ‘may wish to consider’ and, the corollary, the requests that the Minister did not wish to consider at all.

The Federal Court judgments

At first instance, the appellants separately challenged the decisions to resolve their requests for Ministerial intervention without referring them to the Minister on the basis that the departmental officials had exercised executive power unreasonably. In both cases, the Federal Court found for the Minister and dismissed the applications.

A five-judge bench of the Full Court heard and determined the appeals together. The appeals to the Full Court proceeded on the basis that the departmental officers’ decisions not to refer the requests for intervention to the Minister, in purported compliance with the guidelines, did not involve any exercise of statutory power but, rather, were the exercise of non‑statutory powers derived from ss 61 and 64 of the Constitution. The Full Court accepted the decisions of the departmental officers were amenable to judicial review on the ground of legal unreasonableness but found the decisions were not legally unreasonable.

The appeals to the High Court

There were two grounds of each appeal in the High Court. The first challenged the finding that the departmental decision impugned was not unreasonable. By notice of contention, the Minister disputed that any aspect of the executive power of the Commonwealth is conditioned by a common law requirement of reasonableness. This ‘very large question’ was not decided because the appeal was resolved based on the second, logically anterior, ground of appeal.

The second ground contended that the issuing of the guidelines, and the departmental decisions made in purported compliance with them, exceeded the executive power of the Commonwealth to the extent that the guidelines instructed departmental officers not to refer requests in cases they themselves assessed not to have exceptional circumstances. It was this ground that was upheld by a majority of the High Court and was the focus of each of the judgments.

The judgments

The plurality of Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Gleeson JJ confirmed that the power in s 351 of the Act may only be exercised by the Minister personally and cannot be delegated or exercised on the Minister’s behalf by any departmental officer. Their Honours explained that s 351 entrusted the evaluation of the public interest, in substituting a more favourable decision for a decision of the Tribunal, to the Minister alone. This statutory limitation was transgressed by the guidelines and decisions that gave conclusive effect to the consideration of the public interest undertaken by a departmental officer.

Gordon J agreed with the reasons of the plurality but wrote separately to highlight that it is always necessary first to identify the source of a power which is said to be executive power. It is not sufficient to state that the power is ‘non-statutory executive power’ or ‘common law executive power’: at [67]. Jagot J also allowed the appeals, confirming ‘the zone of exclusive Ministerial personal decision‑making power created by s 351 of the Act qualifies both an exercise of the statutory power in s 351(1) and an exercise of non-statutory executive power under s 61 of the Constitution in connection with s 351(1)’: at [252]. While departmental officers can provide assistance, advice, and analysis so that the Minister may exercise any aspect of the s 351(1) power, Jagot J found that in this instance the guidelines impermissibly required the departmental officers to decide matters within the zone of exclusive Ministerial personal decisionmaking power created by s 351: at [254].

In a separate judgment, Edelman J explained that the assessment of whether the departmental officers’ decisions were beyond power firstly required identification of whether any power was exercised by the departmental officials. In relation to this issue, his Honour observed that some of the suggested formulations of that power ‘resembled the bureaucratese of Sir Humphrey Appleby’: at [108]. Edelman J eschewed Sir Humphrey’s periphrastic phraseology and expressed the issue simply as ‘did the departmental officials themselves exercise a liberty that is granted to the Minister personally?’ His Honour found the decision as to which requests the Minister should consider had been made by the departmental officials, which constituted an unlawful exercise of the Minister’s personal liberty: at [114].

Steward J dissented on the basis that each of the impugned decisions was an anterior step that could have led, but ultimately did not lead, to an exercise of power affecting rights and obligations. His Honour considered the application of the guidelines to each appellant did not constitute an exercise of power amenable to judicial review. Each application of the guidelines was an anterior exercise designed to facilitate the provision of advice to the Minister and operate as a screening mechanism for requests the Minister did not generally wish to consider. Adopting the High Court’s language from Kirk v Industrial Court (NSW), Steward J considered the inability to seek judicial review of the application of the guidelines to the requests for ministerial intervention did not ‘create islands of power immune from supervision and restraint’ because in this case no power had been exercised: at [247].

The unresolved ‘very large question’

Davis is also notable due to what the High Court did not resolve, namely whether any aspect of the executive power of the Commonwealth is conditioned by any requirement of reasonableness.

A focal point of the Full Court Appeal was the correctness of Robertson J’s decision in Jabbour v Secretary, Department of Home Affairs [2019] FCA 452, which concerned the similar issue of whether the ground of legal unreasonableness applied to a departmental officer’s decision to not refer an intervention request to the Minister based on the same guidelines.

Robertson J’s legal analysis in Jabbour accepted that the common law provides the conceptual underpinning for the court’s role in judicial review of administrative action involving non-statutory powers. Robertson J held it would be ‘incongruous to have in the common law a principle of statutory interpretation implying reasonableness as a condition of the exercise of a discretionary power conferred by statute, but not to have in the common law any such principle existing outside statutory interpretation’: at [101]. Members of the Full Federal Court had adopted Robertson J’s view, accepting that non-statutory exercises of executive power are amenable to judicial review for legal unreasonableness, albeit they found that the exercise of power was not unreasonable in this case.

By notice of contention, the Minister disputed that any aspect of the executive power of the Commonwealth is conditioned upon a common law requirement of reasonableness. The plurality considered that ‘whether any aspect of the executive power of the Commonwealth is conditioned by any requirement of reasonableness is a very large question’ that ‘need not, and therefore should not, be addressed in the determination of these appeals’: at [7].

Only Edelman J engaged with the issue in obiter. His Honour explained it was unnecessary to determine the issue of unreasonableness as a condition of the legality of the departmental officers’ actions because the decisions of the primary judge and the Full Court incorrectly assumed these actions involved only giving advice and assistance to the Minister. However, in light of the thorough submissions directed at the issue, Edelman J observed the ‘obvious force’ of Robertson J’s judgment in Jabbour that had been adopted by several members of the Full Court and affirmed ‘the fundamental principles of the common law that inform statutory implications must also inform the scope of executive liberty and power which is prerogative or otherwise implied from the creation of a functional Commonwealth polity.’ His Honour also confirmed that any reasonableness requirement for the exercise of an extremely broad nonstatutory executive power will usually involve a high threshold. While the departmental officers’ decision in relation to both Mr Davis and DCM20 did not ‘display exceptional charity and equity – for others, tzedakah or zakah – which is part of the foundations of the grant to the Minister of the liberty and power in s 351(1),’ this may not be sufficient to satisfy the high threshold of legal unreasonableness if that issue were to arise: at [176]. For now, as far as the High Court is concerned, the ‘very large question’ remains at large. BN