- Autumn 2024

- Virtual criminal courts and remote advocacy

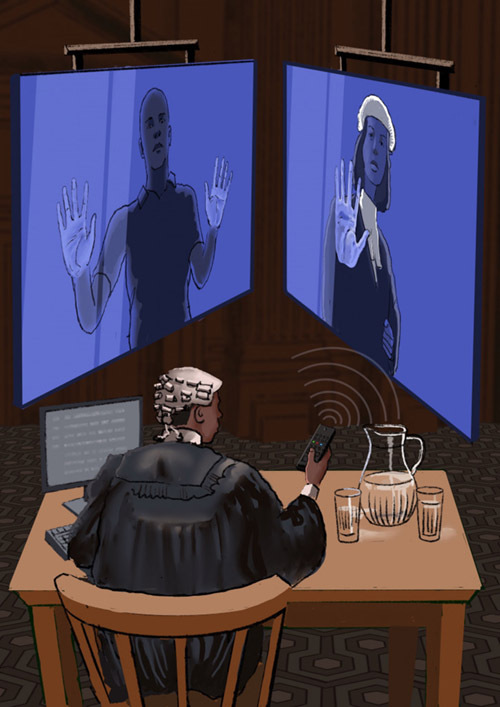

How does the increasing use of audiovisual links (‘AVL’) impact advocacy? Given the developing significance of AVL and special measures in criminal courts, such as the use of pre-recorded out-of-court statements and remote witness suites,2 this article provides an overview of new empirical data regarding how advocacy is transformed by remote modes.

The ‘traditional’ in-person adversarial court setting has long been valorised as a site for live witness testimony, advocacy, and authority. However, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the use of remote hearings, leading to reports documenting the impacts on advocacy and witnesses. For instance, while the Law Society of New South Wales’ 2022 report found many positive impacts to court processes of a purely procedural nature, exceptions included defended hearings and the remote cross-examination of witnesses.3 In 2021, the Bar Councils of England and Wales, Northern Ireland, Ireland, and Scotland stated that remote courts deliver a ‘markedly inferior experience’, including less effective cross-examination and difficulties in witness management, such that in-person proceedings should remain the default position.4 In response to these new challenges, professional bodies such as the NSW Bar Association have issued protocols to assist members with the virtual environment.5

Since 2021, the author has been conducting a national study, funded by the Australian Government, of AVL in criminal justice and the impacts on vulnerable individuals.6 The overall study examines remote court appearance and legal conferencing with vulnerable people, and 85 Australian judicial officers, lawyers, and associated criminal justice professionals have been interviewed to provide their insights. Several judicial officers, prosecutors, and defence lawyers raised issues concerning remote advocacy and witness management, indicating continuing challenges.

Regarding advocacy, some interviewees expressed their preference for physical court appearances. Defence Lawyer DL2 stated that there’s the ‘power of the advocate being in the courtroom with the judge … You’ll get a feel for what the Bench is thinking … the areas that you need to argue, the areas that you don’t need to argue … that’s highly important.’ The ability to ‘read the courtroom’ was significant to Prosecutor P7, who disliked telephone appearances in criminal matters. So too for DL10, who said that ‘I do absolutely notice the differen[ce] in advocacy when you’re on a video link or the judge is on a video link … it makes a difference, and the ability to read body language and pick up cues from judges is very important.’ When remote from the courtroom, DL13 missed the ‘little facial expressions which indicate whether [the judicial officer is] for or against submissions that you’re making.’ A Supreme Court Justice, SCJ1, also acknowledged the significance of ‘the mood of the room – some of the judge’s signals may be picked up’ in the physical courtroom, for instance, if the judge is ‘not buying’ a submission. When AVL is used, these elements are changed, potentially diminishing the potency of an argument according to DL13, who stated: ‘I don’t think [AVL] affects my advocacy. I think the information that’s conveyed is exactly the same, but I think the persuasiveness of the argument is lost.’

Interviewees commented on the ability to cross-examine remote witnesses. While DL1 recognised that remote witnesses won’t have ‘the same visceral reaction as if they were giving evidence in court’, nevertheless they felt that ‘you can still build a relationship with a person over the video and cross-examine them relatively effectively … [not as] effectively as if they were in-person, but you can still build a rapport with them or get them to respond to you and get them angry with you.’ Another defence lawyer, DL22, spoke positively about cross-examining complainants online and how it was ‘probably better’ because questioning necessarily became ‘more efficient’ and ‘economical’. Many prosecutors spoke of the benefits of remote appearance for vulnerable witnesses, although P7 said ‘I have taken many vulnerable witnesses through their evidence-in-chief and I can honestly say that … it’s so much harder to get a vulnerable witness to speak over AVL as opposed to in court.’

The issue of witness management arose during the interviews, including remote witnesses appearing smoking, without wearing shirts, located in a park or while driving; people forget ‘they’re meant to be in a court environment’ (DL29). According to DL22, there is a lack of control of the remote environment, leading to an informality and disruptions from the remote site: ‘[s]o you would be cross-examining a witness … you would hear kids screaming in the background … and then someone would just walk into the background and say … 'hey, babe'.’ This lack of control of ‘what’s happening on the other side of the screen’ (P11) leads to other concerns. Magistrate M4 spoke of the lack of ‘the aura’ and ‘authority of the court’ during remote modes leading bto ‘a greater propensity … for people to prevaricate … otherwise avoid answering questions … I actually think it’s good for them to be a little bit uncomfortable [in the physical witness box], because then they tend to be more honest.’ Not only might remote witnesses evade questions, they sometimes ‘just cut the link’ (District Court Judge DCJ2) if they ‘don’t like the cross-examination’ (DL25).

The informality of remote courts extends also to practitioners, according to SCJ3, who complained that ‘a casualness’ has crept in and there is a need to remind everyone of the ‘formal and solemn process’. This was on top of the perceived ‘progressive de-skilling of advocates in criminal matters’ (SCJ3). However, practitioners are aware of the need to develop new skills ‘if we’re going to be effective advocates on the video link’ (DL11). P5 stated that ‘as a practitioner … you’ve got to be conscious of the need to lead evidence’ in ways that overtly address ‘the deficits’ of AVL.

In summary, some interviewees felt that ‘the oral tradition’ of advocacy is dying (P2) and AVL ‘emasculates … the violent power’ of criminal courtrooms (DL4). However, interviewees also articulated many benefits and realities: ‘we’re in this world now where we accept that the court can be a digital one’ (DL23). BN

ENDNOTES

1 Dr Carolyn McKay is a senior research fellow, University of Sydney Law School; co-director, Sydney Institute of Criminology; and member, New South Wales Bar Association’s Media Information Law & Technology Committee. She is the recipient of an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award: ‘The digital criminal justice project: Vulnerability and the digital subject’ 2021–24 (DE210100586).

2 For example, the Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW) contains various exceptions to oral evidence for certain vulnerable persons, e.g. ss 84, 86, 283C, 283D, 289V, 306M, including specific provisions regarding child sexual offence evidence.

3 The Law Society of New South Wales (2022) A fair post-COVID justice system: Canvassing member views, January 2022. <https://www.lawsociety.com.au/...default/files/2022-02/21051%20Post-COVID%20Justice%20System%20Summary%20Report%20FINAL%20220124.pdf >.

4 <https://www.lawsociety.ie/gaze...remote-hearings-have-multiple-and-multi-faceteddrawbacks--four-bar-councils>.

5 New South Wales Bar Association (n.d.) Remote advocacy skills <https://nswbar.asn.au/practice...information-about-covid-19>.

Dr Carolyn McKay

Dr Carolyn McKay, senior research fellow, University of Sydney Law School, co-director, Sydney Institute of Criminology and Mr Rodney Blake, University of Sydney Law School research assistant, member of New South Wales Bar Association’s Innovation and Technology Committee and BA(Hons)/LLB student.