- Winter 2022

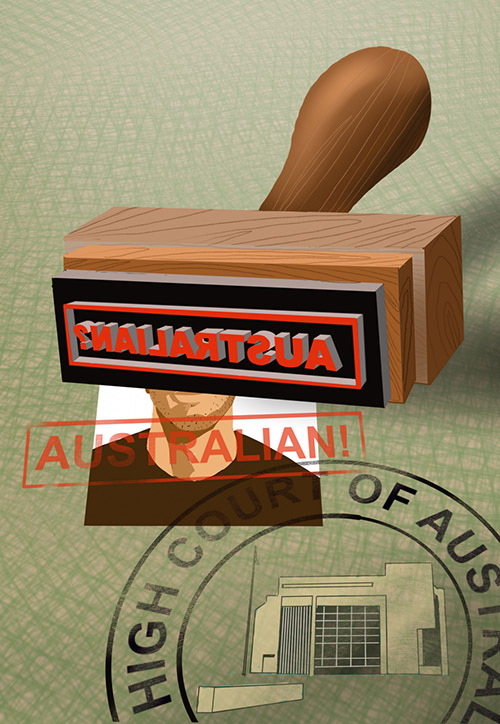

- The power to punish

The High Court has held that the power to deprive an Australian of his or her citizenship is punitive in character. The exercise of that power is hence, exclusively, a judicial function to be exercised in accordance with chapter III of the Constitution. The power could not be exercised by the Minister for Home Affairs.

Introduction

Section 36B(1) of the Australian Citizenship Act 2007 (Cth) provided that the minister may determine in writing that a person aged 14 or older ceases to be an Australian citizen if the minister is satisfied that:

(a) the person:

(i) engaged in conduct specified in sub-section (5) while outside Australia;

(ii) engaged in conduct specified in any of paragraphs (5)(a) to (h) while in Australia, has since left Australia and has not been tried for an offence in relation to the conduct;

(b) the conduct demonstrates that the person has repudiated their allegiance to Australia; and

(c) it would be contrary to the public interest for the person to remain an Australian citizen (see section 36E).

Relevantly, conduct under s 36B(5) includes ‘engaging in foreign incursions and recruitment’. Pursuant to s 36B(2), a determination must not be made if the minister is satisfied that, if the determination were to be made, the person would become a person who is not a national or citizen of any country.

Background

Delil Alexander was born in Australia in 1986. He was an Australian citizen from birth. His parents were Turkish citizens, and so Mr Alexander also became a dual citizen of Turkey from birth.

In April 2013, Mr Alexander left Australia; his outgoing passenger card indicated that he would be overseas for three months. In September 2013, the acting Minister for Foreign Affairs cancelled Mr Alexander’s passport under s 22(2)(d) of the Australian Passports Act 2005 (Cth) – that is, on the basis that ASIO suspected on reasonable grounds Mr Alexander would be likely to engage in conduct that might prejudice the security of Australia or a foreign country. ASIO subsequently assessed that Mr Alexander had ‘likely’ joined ISIS by August 2013, and had ‘likely engaged’ in foreign incursions and recruitment on or after 5 December 2014.

In November 2017, Mr Alexander was apprehended by a Kurdish militia in Syria, and subsequently transferred to the custody of Syrian authorities. On 31 January 2019, he was convicted and sentenced to imprisonment by a Syrian court. Although later pardoned by the Syrian government, he remained in detention for various reasons, including that he could not be released into the Syrian community nor repatriated to Turkey or Australia.

On 2 July 2021, the minister made a determination pursuant to s 36B(1) that Mr Alexander ceased to be an Australian citizen. That determination stated that the minister was satisfied that Mr Alexander had engaged in foreign incursions while outside Australia, demonstrating a repudiation of his allegiance to Australia; that it would be contrary to the public interest for Mr Alexander to remain an Australian citizen; and that Mr Alexander would not become stateless by reason of the determination. In response, Mr Alexander (by his litigation guardian) sought declarations in the High Court that s 36B was invalid, and that he retained his Australian citizenship notwithstanding the purported determination.

First argument – ‘aliens power’

Mr Alexander argued that s 36B was not supported by s 51(xix) of the Constitution (the ‘aliens power’), insofar as he – as a person who was an Australian citizen from birth – could not thereafter be regarded as an ‘alien’. That argument was rejected by the court. Kiefel CJ, Keane and Gleeson JJ observed, in this regard, that parliament has the power under s 51(xix) to ‘attribute the constitutional status of ‘alien’ to a person who has lost their citizenship, and to define the circumstances in which that will occur: at [35]. Just as Mr Alexander gained his citizenship through the operation of statute, statute could also limit his rights of citizenship, ‘including by providing for the circumstances in which they may be lost’: at [38]. It was consistent with the ordinary meaning of the term ‘alien’ for a person whose conduct was inimical to Australia’s interests to therefore, by a law of the Commonwealth, forfeit rights of citizenship conferred by parliament, and thereby become an alien: at [63].

Gageler J agreed with the substance of Kiefel CJ, Keane and Gleeson JJ’s reasoning in respect of the ‘aliens power’: at [98]. While Gordon J found it unnecessary to decide whether Mr Alexander fell within the category of persons ‘who could not possibly answer the description of ’aliens‘ in the ordinary sense of the word’ (at [152]), her Honour accepted that – to the extent that s 36B(1)(a) covered the ‘paradigm case of implicit renunciation’ of allegiance (of spying or fighting for an enemy state at war with Australia, or service in the armed forces of a declared terrorist organisation) – s 36B was within the scope of the aliens power (at [154]).

In also rejecting the argument, Edelman J cautioned that the meaning of the term ‘alien’ urged by the minister ‘has the likely consequence that potentially half of the permanent population of Australia are aliens, being dual (or more) citizens, being born overseas, or having at least one parent who does not hold Australian citizenship’ – but acknowledged that ‘the defendants’ approach was only an incremental extension of the present state of the law concerning the application of the aliens power’, and that none of the relevant decisions were challenged in the proceedings (at [182]–[183]; see also [202]–[203]). His Honour further accepted that the aliens power permits the parliament to legislate, as with s 36B, ‘in relation to non-aliens who act in a manner that has been described as a repudiation of their allegiance to Australia’: at [185]; see also at [234].

Steward J similarly accepted that a law which denaturalised a citizen ‘because that person took a step or steps that represented a fundamental and lasting rebuttal of allegiance to Australia’ would be authorised by s 51(xix): at [289].

Second argument – improper exercise of judicial power

Mr Alexander also argued that s 36B was invalid because it reposed the exclusively judicial function of punishing criminal guilt upon the minister (rather than upon a court exercising power in accordance with chapter III of the Constitution). A majority of the court accepted that argument.

Kiefel CJ, Keane and Gleeson JJ found that

… [t]he consequences of a determination under s 36B for the citizen, the legislative policy which informs the operation of s 36B, and a comparison of the operation of s 36B with the provisions of s 36D (which authorise the same consequences for the citizen only upon conviction after a trial

all pointed to the same conclusion, namely: ‘that the power reposed in the minister by s 36B(1) is a power which Ch III of the Constitution requires to be exercised by a court that is part of the federal judicature’ (at [70]).

Their Honours emphasised, in this regard, that

… the principal purpose of s 36B is retribution for conduct deemed to be so reprehensible as to be ‘incompatible with the shared values of the Australian community’ (citing s 36A of the Australian Citizenship Act),

which was consistent with ‘the long- held understanding of exile as a form of punishment’: at [75]. That sanction – deprivation of Mr Alexander’s entitlement to enter and live at liberty in Australia – could only be imposed upon satisfaction by the minister that Mr Alexander engaged in conduct that is so reprehensible as to be deserving of the dire consequence of deprivation of citizenship and the rights, privileges and immunities associated with it: at [96].

The power to determine the facts enlivening that power could only be exercised, in accordance with Ch III of the Constitution, exclusively by a court which was part of the federal judicature: at [96].

Gageler J agreed with the substance of Kiefel CJ, Keane and Gleeson JJ’s conclusions in respect of Ch III (at [98]), while reiterating and emphasising the clear distinction between a law such as s 36B and laws imposing standards in the context of licensing or professional regulation (at [110]). Gordon J similarly found that s 36B was contrary to Ch III of the Constitution, insofar as it conferred upon the minister the power to impose a punishment – involuntary cessation of citizenship – for the person’s past conduct, and to thereby impermissibly exercise judicial power: at [157] and [173]. Edelman J similarly found that s 36B was punitive in character (rather than ‘political’ or ‘protective’), and hence impermissibly conferred exclusively judicial power upon the minister: at [247] and [253].

Steward J dissented on this issue. While his Honour accepted that denationalisation could be penal in nature (at [326]), his Honour emphasised that the power to impose penalties is not necessarily a power exclusively reposed in the judicial branch (at [328]); that the federal executive can (in some circumstances) impose detriments and penalties based on the fact that a crime has been committed (at [329]); that it has never been an essentially judicial function to make orders denationalising a person (at [332]); that the minister’s task was not to determine whether the conduct specified in s 36B(5) constitutes the commission of any crime, or to determine guilt or innocence (at [336]); and that the purpose of s 36B was not to punish, but rather to ‘recognise a person’s repudiation of her or his allegiance of Australia and to prescribe a consequence for this repudiation, namely denationalisation’ (at [337]). His Honour further noted that the courts retained the power to review an exercise of power under s 36B(2) to cancel citizenship, and hence to ensure that power is exercised lawfully (at [341]).

The court thus made declarations that s 36B is invalid, and that Mr Alexander remains an Australian citizen. BN