- Winter 2024

- The New South Wales Supreme Court’s role in the creation of New Zealand

Perhaps of all the accolades bestowed upon the Supreme Court of New South Wales as it turns 200, that of nation builder might be one that slips under the radar.

According to the orthodox telling of the New Zealand nation-building myth, 13 Māori chiefs in the north of the North Island petitioned King William IV in 1831, seeking protection from lawless British subjects who were proliferating throughout the islands.

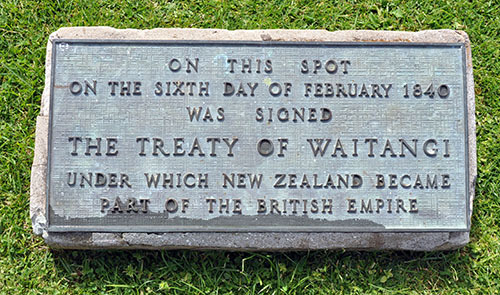

The British responded by transplanting James Busby from New South Wales to Waitangi in the far north of New Zealand in 1833 as its official British Resident. Busby then encouraged the northern chiefs to confederate a group of united tribes, declare New Zealand as an independent nation in 1835, then cede that sovereignty to the British at Waitangi on 6 February 1840.[1]

This article looks at one of the unlikely catalysts for the 1831 petition and the 1835 Declaration of Independence and the subsequent incorporation of New Zealand as a colony of the United Kingdom in 1840: ‘the unstable, partial, and largely ineffectual jurisdiction of the New South Wales Supreme Court’.[2]

New South Wales claims New Zealand

In 1814, Governor Macquarie simply proclaimed that New Zealand would be a dependency of New South Wales.[3] Macquarie then appointed a magistrate, Thomas Kendall, to go on circuit throughout the fleshpot(s) of the Bay of Islands where his jurisdiction was unclear, his resources meagre, and he operated without a court, any means of enforcement[4] or an associate.

The British Act of Parliament giving rise to the charter did not address Macquarie’s proclamation directly, but extended jurisdictional power to the newly created Supreme Court to hear and determine all ‘treasons, piracies, felonies, robberies, murders, conspiracies and any other offences ... committed on the islands of New Zealand’.[5]

The Third Charter of Justice itself proclaimed in 1823 that the Supreme Court’s criminal jurisdiction would extend to serious crimes committed on the islands of New Zealand and Tahiti, as well as any other island, country or place in the Indian or Pacific oceans not subject to the King’s or any other European state or power.[6]

It was in this way that criminal jurisdiction over British subjects in New Zealand was extended. It did not extend to the Māori, who were acknowledged to have their own rules and customs with which the Supreme Court could not interfere (R v Stewart [1831] NSWSupC 31). This created what Wayne Rumbles, Associate Professor at the University of Waikato, calls the spectre of jurisdiction and what the current chief justice noted was a jurisdiction ‘of sorts’.[7]

Slow, incomplete and expensive

Shaunnagh Dorsett argues that by the early 1830s the dual jurisdiction of Maori and the Supreme Court had created a jurisdictional no-mans land that attracted acharacters of ill-repute8. While post-dating the 1831 petition, an example of the problems with dispensing justice ‘across the ditch’ (as well as a salutary lesson on the dangers of sailing hungover) was illustrated in Lewis v Lambert [1835] NSWSupC 73.

Lewis and a mate, both able seamen on the Cape Packet sailing across the Tasman, saved up their grog, got drunk, struck the captain and were ‘otherwise outrageous’. Nursing high seas hangovers, the two were denied the hair of the dog, and Lewis and his co-drinker, much like a barrister in mid-December, ‘then swore they would do no more work, and persisted in that determination’.

When he reached New Zealand, the captain of the Cape Packet asked for the assistance of Busby, the British Resident, who handballed the problem to Captain Lambert of the HMS Alligator, a Royal Navy ship in port nearby. Lambert took charge of Lewis and conveyed him back to Sydney, where he was promptly discharged on the basis that a Bench of justices could not take cognisance of a complaint against Lewis in the absence of the captain of the Cape Packet.

Lewis sued Lambert for false imprisonment and won on appeal, the verdict being entered in his favour for one farthing damages.

The difficulties in hearing the case, the cost and the time it took to deliver judgment were remarked upon in The Australian in its role as the unofficial court reporter. Moreover, the false imprisonment at the centre of the case arose out of a necessity to transport Lewis back to Sydney and the failure of the Cape Packet captain to lodge civil charges in Sydney, given he was on the seas.

The incomplete jurisdiction, based as it was, at least partly, on an assumption as to the uniformity of the European presence in New Zealand (that is, the troublemakers were British) was further demonstrated in R v Doyle. Upon being charged with attempted murder and aggravated robbery in the Bay of Islands, Doyle argued in Sydney that he was not a British citizen, having been born in the USA, and therefore was not subject to the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction. The court responded by ‘imbuing’ him with the status of a British subject due to his being ‘late of Sydney’, then sentenced him to be hanged. In this way the Supreme Court put to death a ‘judicially imagined’ British subject.[9]

The problem and the solution

One effect of the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction of sorts over New Zealand and its imperfections was to create two contradictory perceptions in the minds of the groups who later come to sign the Treaty of Waitangi.

In the minds of British subjects and the officials of the British Colonial Office, the reports of court proceedings in widely read and available newspapers left the impression of an homogenous and largely and ‘imagined community of British living in New Zealand even though they numbered less than 2,000’.[10]

Equally, ‘[o]ne repeated threat described in the papers was the lawless uncivilised European who was not only a danger to the emerging British community but also to Māori. The media helped construct the sense that both were at risk from certain criminal behaviours and lawlessness and this was seen as justifying an increase in legalisation and enforcement procedures more akin to those in Britain.’[11]

And so it was that these contradictory perceptions were reflected in the 1831 petition to King William IV by the 13 northern chiefs. In the English language version of the petition drafted by the Committee of Missionaries, the drafter seeks help from the beneficent English King for protection against troublesome settlers and escapees and, of course as a boilerplate, the French.

But in the Māori language version, they ask that the British deal with the transgressions of its subjects against the Māori quickly ‘or else the Māori jurisdiction will be righteously applied’.[12] The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court was part of the problem; it was also, in the eyes of the 13 chiefs, part of the solution.

Rumbles concludes:

A sense of community, created through the assertion of the somewhat incomplete jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, had been strengthened by the homogenising influence of the spectral nature of the jurisdiction. This fiction of sameness and uniformity, as well as New Zealand’s well-mapped geographical boundary and bounded territory, were essential to the pre-political and cultural formation required to create an organic jurisdiction.

New Zealand in the late 1830s had the necessary elements for the creation of an organic jurisdiction: a pre-political community, imagined as sharing similar goals and culture — the British subject and a bounded mapped territory. The difficulty from the perspective of the colonisers was that Māori had the economic, demographic, political and cultural upper hand. Just as the extension of the New South Wales jurisdiction had been justified in terms of the protection of Māori from the lawless European, so too the adoption of the Treaty of Waitangi was justified in terms of protection of Māori from the anarchic growing settler population: law within an organic jurisdiction was required to remain civilised.[13]

In this way then, the Supreme Court can add to its achievements its role as a catalyst in the creation of a country.

ENDNOTES

[1] The nature of some of these events remains contested in New Zealand, not least the notion that the Māori were a single body politic in the lead-up to the Treaty of Waitangi, and the fact that the Māori language version of the treaty ceded governorship (Kãwanatanga) consistent with their 1831 petition seeking protection and regulation of their relationship with British citizens, rather than sovereignty as was stipulated in the English version.

[2] Wayne Rumbles, ‘Spectre of Jurisdiction: Supreme Court of New South Wales and the British Subject in Aotearoa/New Zealand 1823–1841’ (2011) 15 Law Text Culture 209–232, 209.

[3] The Official Yearbook of the Commonwealth of Australia entry for 1814 reads: ‘Australia proclaimed a dependency of New South Wales’.

[4] Robert McNab, From Tasman to Marsden: A History of Northern New Zealand from 1642 to 1818 in the Historical Records of New Zealand vol 1 (Wellington New Zealand Government Printer, 1908) (J Wilkie and Co Ltd, 1914); Rumbles (n 2) 210.

[5] New South Wales Act 1823, 4 Geo IV c 96.

[6] Ibid s 3.

[7] Foreword to Keith Mason AC KC and Larissa Reid (eds), Constant Guardian, Changing Times: The Supreme Court of NSW 1824–2024 (Supreme Court of New South Wales, 2024).

[8] Shaunnagh Dorsett ‘Mapping Territories’ in Shaun McVeigh (ed) Jurisprudence of Jurisdiction (Routledge-Cavendish, New York, 2007)

[9] Rumbles (n 2) 219.

[10] Ibid 220.

[11] Ibid 221.

[12] Manuka Henare, ‘The Maori Leaders Assembly, Koroipo Pa 1831’ in J Binney J (ed), Te Kerikeri 1770– 1850: The Meeting Pool (Bridget Williams Books in association with Craig Potton Publishing, 2007).

[13] Rumbles (n 2) 223.