- Winter 2024

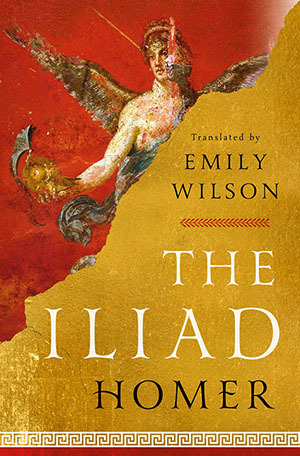

- The Iliad By Homer, translated by Emily Wilson (WW Norton & Co, 2023)

In part II of this two-part book review, Emily Wilson’s translation of The Iliad (2023) is reviewed. Part I, in Bar News Autumn 2024 edition, reviewed Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey (2017).

Emily Wilson’s translation of The Iliad (2023) is a poem of sound and fury that chronicles the glory, tragedy and futility of war. Though a chronological prequel to The Odyssey (2017), covering the 10th and final year of the Greeks’ siege of Troy, by dint of its ambitious scope and adventurous complexity it reads much more like a sequel. ‘Tell me about a complicated man’ is how the story of Odysseus’ long journey home began. ‘Goddess, sing of the cataclysmic wrath’ opens The Iliad.

As with The Odyssey, Wilson has adapted The Iliad to follow the rhythmic cadence of the iambic pentameter. But, unlike her preceding translation, which matched the line count of the Homeric script, Wilson admits, in a translator’s note that blends commentary with confession about the writing process, ‘after many drafts and experiments, I reali[s]ed that I needed to use more lines than the original’.

This extension in length is felt, but rarely adversely. Whereas The Odyssey told the story of the titular individual and those in his immediate orbit, The Iliad tells the story of a place – a legendary city then known to the Greeks as Troia or Ilios – and its fall. It is on this land that Greek heroes Agamemnon and Achilles do battle against Trojan protagonists Hector and Paris. It is a conflict prompted by the off-page kidnapping of Helen, the wife of Menelaus (the brother of Agamemnon) by Paris (the brother of Hector) and concluded, not by the demise of Troy via a wooden horse left at its gates, but by the killing of principals on each side.

Each side leads large armies containing dozens of patronymic units – fathers, sons, and brothers – with their own stories, many of which are told through brief scenes of combat. Above and behind these forces loom the Olympian gods: Hera, Athena and an ambivalent Zeus, favour the Greeks, while Ares, Aphrodite and the impassioned Apollo support the Trojans.

It is amidst the thunderous roar of battle, the fretful quietude of each party’s encampments, and the heavenly but querulous realm of the deathless gods that the plot is progressed. Characters deliver long speeches to each other between montages of fighting (as Wilson observes: ‘almost half the poem consists of direct speech’). But the conflict is also internecine. Achilles, the Greeks’ finest warrior, admonishes Agamemnon, their leader, in Book 1 (‘The Quarrel’): ‘Cannibal king, you eat your people up! You are a leader of nonentities!’ The Iliad is packed with this kind of trash-talk.

There are also moments of levity. An early confrontation between Glaucus, of the Trojan side, and Diomedes, on the Greek side, is exemplary of this. On meeting, the two introduce themselves, chat amiably about their lineages and priors, realise through their forebears that their families are friendly with each other’s, agree to desist from attacking the other, and ultimately decide to ‘exchange our arms and armour with each other, so that other men will know that we are proud to be each other’s guest-friends through our fathers’. The humour in scenes like these is simultaneously dry and broad. The skewering of social norms and the tension between hostility of war and the hospitality of the aristocracy sometimes feel like a Key and Peele skit, or an episode of Seinfeld, but with swords and sandals.

Like The Odyssey, there is much from The Iliad for the antipodean barrister of the 21st century. A leader would do well to encourage their juniors in the manner that Nestor of Gerenia, an older commander of the Greek forces, speaks of the troops under his command: ‘This is the privilege of age. My juniors / confident in their strength, will be the ones / to hold and hurl the spears.’

It is in this way that the allegory of war illuminates the practices and principles of the legal profession and the contest of litigation. The similes of battle did not inspire me in thoughts of the adversarial process, but the scenes antecedent and adjacent to the conflict reminded me of the Bar. It is gauche, for good reason, to boast openly about ‘winning’ a case.[1] The Iliad reminds us that the triumphs of individuals are the work of higher powers.

Sometimes this is literal, as when Apollo redirects Teucer’s arrow, aimed at Hector, to pierce and slay another. At other times, it is indirect, as when Poseidon takes mortal form to rally the Greek troops through speech and inspire a successful counter-offensive against a dominant Trojan push. This is not to say that individual effort and skill are absent from the resolution of a case; rather, it is to acknowledge that the race does not always go to the swift nor the battle to the strong, but that time and chance happen to all.[2]

The Iliad is not without its flaws. Its scope and complexity, and consequent length, is, at times, bogged down by the cataloguing of ships and moments of combat repetitiously compared to a lion attacking deer on a plain. These moments are thankfully broken up by sections such as Diomedes’ and Odysseus’ stealth mission in Book 10 (‘Espionage by Night’), Hera’s seduction of Zeus to lull him into slumber in Book 14 (‘An Afternoon Nap’), and Achilles’ impromptu facilitation of sporting contests for the Greeks in Book 23 (‘Funeral Games’).

Wilson’s translation of Homer reminds us that interminable conflict of our working days can involve glory, tragedy and futility – sometimes all at once. But it is the deeply human moments, and our place within a universe much larger than Philip Street, that provide our days with colour, joy and depth.

ENDNOTES

[1] Editor’s note: It has been observed that this affliction increases with seniority. As Cicero says in De senectute: ‘There is no need of my speaking of myself, though that is an old man's habit, and is conceded as a privilege of age’ before immediately observing ‘Do you not know how very often Homer introduces Nestor as talking largely of his own merits?’.

[2] The Bible, Ecclesiastes 9:11.