- Autumn 2024

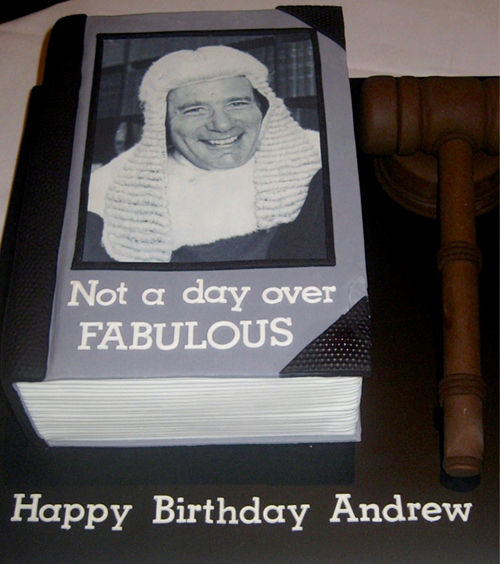

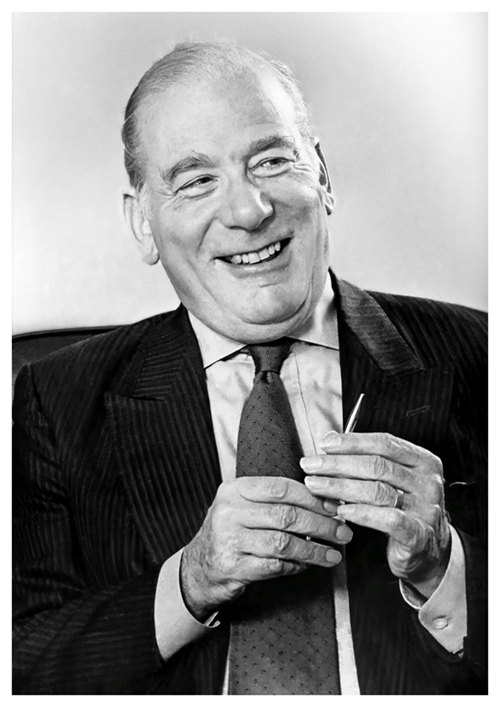

- The Honourable Andrew John Rogers AO KC 1933–2024

The Honourable Andrew John Rogers AO KC died on 4 February 2024. Commercial litigation in New South Wales and throughout Australia is, to a pervasive extent, imprinted with his efforts between 1979 and 1993 as a judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales. At a broader level he is largely responsible for the case management approach to litigation.

He was born on 30 April 1933 into a Jewish family in Budapest. His mother, brother and Andrew survived the Nazi and Arrows Cross terrors under the inspiring protection of a Hungarian family to whom he remained devoted throughout his life.

After World War II, due to the determined efforts of his mother Kati, his family escaped Europe and, after a period in India, arrived in Australia in 1947.

He completed his secondary education at the Cranbrook School and then studied law at Sydney University. Andrew joined the Bar in 1956 taking silk in 1973. He had a broad practice concentrating on commercial, company and constitutional law.

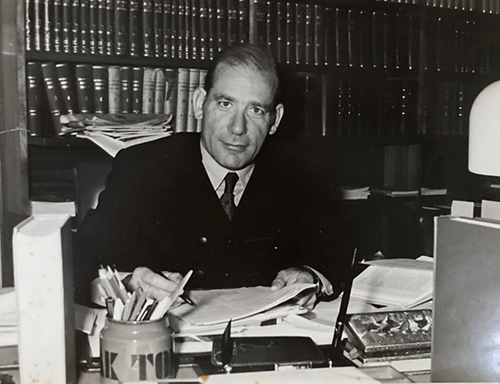

On 14 December 1979 he was appointed a judge of the Supreme Court and assigned to act as the judge in charge of the Commercial Causes List in the Common Law Division, which was designed to cater for the disputes of the commercial community. That list operated under a practice note issued in 1972 ([1974]) 1 NSWLR 144), which in rather short compass provided for its conduct. It placed no real demands on clients and the profession to pursue commercial cases with diligence. As Andrew observed, ‘in any litigation the parties are not equally anxious to achieve an early hearing’. The courts faced a culture which did not prioritise, let alone demand, the swift resolution of commercial disputes.

The extent of delay in moving a case into the Commercial List, Andrew observed, was ‘beyond belief’. The procedural steps adopted possessed a routine quality often irrespective of any specific need.

The times afforded opportunities through various procedural steps to impose burdens on the opposition both in terms of time and expense. For example, beyond the expense of discovery, a regular duty of a commercial junior was to draft a lengthy list of interrogatories, which generated a corresponding duty for another junior to draft responses, which often involved a series of arcane objections to the questions. Andrew observed that usually no more than two or three were used in a hearing.

He was acutely aware of these practices and, by the end of his first year on the Bench, exposed many of his concerns to the profession.

He was by no means alone in recognising the problems and made reference to the concerns expressed by his colleagues on the court and judges in other jurisdictions. What ultimately set him apart from all judges in the country was his determination and ability to see through a thoroughgoing reform of the processes of commercial litigation. He did receive the enthusiastic support of his colleagues and the Chief Justice, Sir Lawrence Street.

His determination was bred of a number of qualities, but the overriding impetus was the need for the resolution of the real disputes between the parties quickly and cheaply. The invidious position of the small business faced by litigation was a constant concern for him.

This did not entail the sacrifice of a just and principled hearing, but he was accurately aware that demands to undertake every conceivable step that the common law procedure provided in the pursuit of justice were often calculated to frustrate that end.

Andrew effected a revolution in the Commercial List on Thursday and Friday mornings. The central tool he deployed was to interrogate the legal representatives of the parties about the issues in the litigation. He possessed a simply amazing ability to absorb and distil the essence of quite complex disputes.

This was no mere exercise to impress, but rather, to require of the legal representatives a frank and informed debate designed to isolate the true issues. That achieved the basis for an informed discussion as to what procedures were reasonably required to progress the matter to hearing as efficiently as possible.

Andrew recognised that he required the cooperation of the profession and clients. Stories abound of the profession colliding with his will. They are a more appropriate to a wake than this obituary, but the truth is that in a relatively short period of time almost everyone fell in with his program.

This was for a number of reasons, but primarily, because the commercial community appreciated his efforts to simplify and expedite resolution of its litigation.

However, central to its success was that all sections of the profession came to appreciate that the past practices were often an arid waste of time and money, which reflected poorly upon them.

The way the commercial list was conducted evolved over the years. One of Andrew’s great qualities was his constant preparedness to experiment with new procedures to address perceived difficulties in getting to the heart of the matter. Not all were successful. He experimented with narrative statements replacing pleadings in complex litigation but soon found that that was unmanageable. He accepted the failure and moved on.

Experienced practitioners would know that a knee-jerk rejection of a novel suggestion from the Bench was not utility maximising and that it was wise to ask for the matter to be stood in the list while the new twist was evaluated.

The reputation of the court for efficiency and expertise grew due to the reforms and the diligence of Andrew and the small group of judges who worked with him. That contributed to a vast increase in the case load, aided by the advent of the cross-vesting legislation scheme and the expansion of rights in other pieces of legislation. Chief Justice Bell, in his eulogy delivered on 15 February, spoke of the herculean burden Andrew assumed, often dealing with 80 to 100 matters each Friday. To prepare himself for a Friday list he often studied till midnight on Thursday.

On 21 December 1987 he was appointed the first Chief Judge of the Commercial Division. Practice in that Division was governed by Practice Note 39 ((1986) 6 NSWLR 119), which was issued on 12 November 1986 by Chief Justice Street but was known to be a creature of Andrew and his fellow commercial list judges. It succinctly stated the approach of the Commercial Division was that ‘all concerned are required to focus on the formulation of the procedures in each case which will most effectively minimise cost and reduce delay’. That encapsulates the essence of the now ubiquitous case management approach to litigation.

The Practice Note addressed a great range of the sources of delay and expense, pleadings, particulars, discovery, and interrogatories and made clear all were to become servants to the central aim. The Note still contains much that lies in the heart of commercial litigation both in New South Wales and throughout Australia. It governed the conduct of the Commercial Division under Andrew’s leadership.

While the procedural revolution he initiated is most nearly welded to his name, the New South Wales Law Reports also demonstrate that he was a fine lawyer, by no means solely in the commercial sphere where he delivered many groundbreaking judgments, including AWA Ltd v Daniels (1992) 7 ACSR 759 where he explained the duties of directors and auditors. In the early years his reported decisions are most often in the administrative law field.

To achieve what he did, he deployed more than just intellectual ability and drive. He was a captivating character who had a wonderful voice, a self-deprecating wit, a facility for eviscerating sarcasm should he suspect humbug, and a capacity for kindness which made the heart of many a junior barrister soar.

He had an indelible effect upon the cohort of legal practitioners who worked in the Commercial List and the Commercial Division. Andrew retired from the court on 3 May 1993. At his farewell he returned to his concern that the law needed to address the balance between cost and achieving a fair result.

A singular omission from Practice Note 39 is any provision for alternate dispute resolution. Andrew embraced it after his retirement, establishing with Professor Tania Sourdin, Endispute. He became a recognised international arbitrator, active in the London Court of International Arbitration and the International Chamber of Commerce among others, and joined the Court for Arbitration for Sport.

He served as chair of the Audit Quality Review Board and various Cooperative Research Centres and sat on numerous other boards, including the New South Wales Treasury Corporation, the Garvan Institute and, for a short period, Westfield Group.

He was an adjunct professor in business and law of the University of Technology and the inaugural Chancellor of Southern Cross University. He acted as Patron of the Ted Noffs Foundation, which focusses on helping young people with drug crime and mental health issues.

The Honourable James Allsop AC wrote, of his experience as a junior counsel practising in commercial litigation under the at times daunting but always testing supervision of the brilliant Justice Andrew Rogers, that one learnt that only points worth manning would be tolerated; complete preparation was compulsory; dispatch and clear thinking were essential; cooperation with one’s opponents was essential. Practice there instilled in succeeding generations of lawyers how to run commercial litigation ‘quickly, fairly and cost effectively’.1

That tribute reflects the impression Andrew Rogers had on a generation of lawyers and litigants. Practitioners who did not see or experience Andrew in full flight still benefit from his achievements. BN

ENDNOTES

1 2013 Clayton Utz Sydney University International Arbitration Lecture.