- Winter 2022

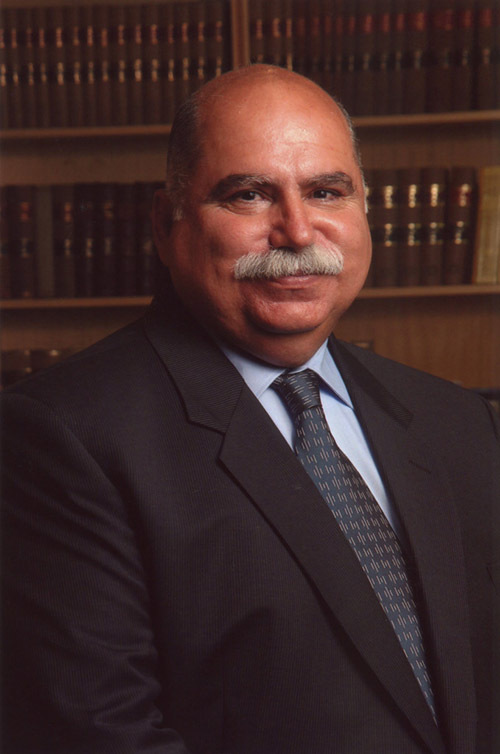

- The decent best: the late Judge Peter Zahra

On Sunday 8 May 2022, Judge Peter Zahra passed away surrounded by his loving family. Milestones in his professional path hint at Judge Zahra’s s steadfast commitment to criminal justice for which he was so well known: solicitor at the Legal Aid Commission commencing in 1981, public defender in 1989, silk and senior public defender in 2001, judge of the District Court in 2007. To fairly comprehend his lasting influence, we must step through moments which were not necessarily, of themselves, milestones.

From early in his career Judge Zahra pursued a meaningful contribution to criminal justice, in the early 1980s working for an Aboriginal Legal Service in the Blacktown area and then shouldering much of the workload at busy Blacktown Local Court for the public solicitor. Ron Hoenig MP remembers him there, doing a mountain of work: ‘only drawing the line at taking instructions when accosted by prospective legal aid clients at the urinal! He even found time to assist in committals as amicus.’ Upon Judge Zahra moving to Central Local Court, the work was shared with Warwick Hunt (as Hunt DCJ was then). Positioned in the Central police cells over the mid 1980s, pulling in tandem, Hunt DCJ recalls their time in those cells as the happiest of professional experiences. Adding to the sense of energy, Judge Zahra swept his colleagues up in novel social activities – nativity plays funded by sales of Fosters beer and glasses of tepid cask wine, talent quests, and running stakes on which of his colleagues could fit inside the metal public-issue court lockers.

Accompanying Judge Zahra’s sense of fun and great ability as a lawyer was a deep humility of character which, from those early days, underpinned his professional decisions and endeavours. Everybody recognised it and loved him for it. Reginald Blanch QC, New South Wales first DPP, quickly saw his qualities and Judge Zahra became a Crown prosecutor for a time. In 1988 a position was advertised with the Public Defenders and Judge Zahra knew where he was best suited. His appointments as a public defender and then senior public defender were large contributors to what District Court Judge Flannery, counsel on the floor at the time, describes as a golden age of public criminal defence in New South Wales.

At the Public Defenders, Judge Zahra was an egalitarian and effective manager. His personality made the workplace happy and rewarding. He ensured the floor’s barristers had a fulfilling mix of work and advanced their skills.

More so, Judge Zahra was a magnificent leader of the floor. He inspired the barristers around him by himself taking on the hard cases. And they were the hardest of trials – Folbigg, mired in unthinkable tragedy and complex science; abattoir worker Leonard, a particularly macabre homicide; Saxon, band promoter and drug dealer who escaped from Long Bay in a laundry van; a 13-year-old girl, acquitted of murder on self-defence grounds after stabbing her mother’s de facto partner; the Skaf gang rape case which caused such revile in the community.

Justice Button, a public defender during those years, remembers Judge Zahra’s commitment to the interests of justice as being absolute: ‘he was selfless and self- deprecating but he did murder trial after murder trial and they were the toughest ones. Really.’ The Hon Justice Dina Yehia recalls that time as a public defender as a profound experience, that it really was a golden age: ‘the work he did inspired great pride in us all’. Under his stewardship, almost a third of the floor were senior counsel by the time he became a District Court judge, from one silk when he began. Judge Zahra lived the promise of representing the most maligned and unpopular, and in hard cases most difficult to successfully defend, and motivated the best from those on the floor.

Inspiration was not confined to his immediate colleagues. He was respected for his representation of the Kings Cross injecting room. His interactions as counsel were imbued with decency. Justice Bellew recalls his very first trial, which was against Judge Zahra:

I had been at the bar about a month. He was the ultimate professional. He knew it was my first trial, and was very encouraging and complimentary in his words to me at the end. It struck me watching him – although trials are adversarial, they can be conducted in a professional and courteous way. He demonstrated how advocates can behave respectfully, and simultaneously uphold the interests of their client and maintain their professional responsibilities.

After his appointment to the District Court bench, Judge Zahra soon became an essential presence by his soundness of judgment and high criminal law skill. Judge Flannery relates that,

Being so sound meant that other judges regularly consulted him about tricky legal issues… Being so sound also meant he was yet again given the most difficult cases. Not just the cases that have been in the press, but also the cases that required a great deal of hard slog.

Sound judgment is a common thread which emerges time and time again when colleagues relate Judge Zahra’s attributes. Judge Yehia (as Justice Yehia was then), managing the list in Court 3.1, would refer long and complicated trials to him because of confidence in his discretion and intellect. Justice Bellew, as counsel, appeared before him: ‘he was unfailingly courteous: an outstanding judge, an outstanding criminal lawyer, but even more, an outstanding person.’

Judge Zahra was an exemplary judge but, in Tom Kelly’s words, was ever morally non-judgmental. While Judge Zahra was senior public defender, Justice Button remembers, he was never judgemental about personal issues in the lives of those on the floor, however different their life choices were from his own, and he lived by closely held, fundamental values of loving and looking after others.

Throughout, Judge Zahra’s devotion to his family was paramount. He was unwavering in his commitment to the law but, Judge Haesler describes pithily, ‘the whole thing was family oriented’. Somehow, and with great discipline, Judge Zahra made both his vocation and family life work, and was involved in the day-to-day lives of his family: up and down the sidelines at soccer on the phone, writing a judgment at the kitchen table surrounded by lively chaos, or taking the family to London and Malta in his breaks. Besides, Judge Haesler comments, his kids had a tracker and were onto him if he was actually still in chambers when he said he was walking to the carpark.

While Judge Zahra’s role in administering justice in the work of the District Court is universally recognised, it is the quiet shared moments which are equally treasured now. All agree that Judge Zahra was a very funny man. He loved jokes, and he would share his love of them by stopping colleagues in the corridors, or in individual chambers, to relay detailed humorous stories and enjoy the richness that plays on words could bring to a moment. Judge Hock recalls that he would lament, laughing, in light of his long service at the Public Defenders, that his chambers in court were in the ‘Crown prosecutors’ wing’ – because a number of former prosecutors had their chambers nearby – and that he was outnumbered. For Judge Yehia, he brought welcome, momentary pauses in a fluid environment:

He would tell a joke, or a funny story, and what I loved most about that was that he took his time and he would tell the details. I would reflect later on what he had said, and appreciate that it is so important to be in the moment and to enjoy that moment. The way he spoke, and wrote, was considered and temperate and patient.

Judge Zahra loved the fun of words, but there was also such wisdom in his ability to create the space, in his mind and in his day, to allow that fun to play out. Justice Bellew again:

He would always stop and chat, and always showed an interest in how you were and what you had to say. It was a genuine interest, and was never simply for the sake of it.

Judge Hock echoes that Judge Zahra’s door was always open for advice, or just to chat – busyness was never a bar – and he was always interested in what other judges were doing. He understood the importance of listening, and of engaging with a problem, and throughout his career colleagues drew upon his careful consideration. His conscientiousness and good humour never abated. Judge Hock recalls that when he returned to the court after a break and a period of illness, he told everybody that the time away had only confirmed one thing: he was not ready to retire. He was very happy to be back. He loved his work.

Judge Zahra’s judgments were rarely appealed; successful appeals were even more rare. Upon his death, the Honourable Margaret Beazley AO QC, Governor of New South Wales, recalled from her time on the Court of Criminal Appeal that,

His judicial work was of the highest quality and integrity as I found on that rare occasion or two when his work ‘graced us’ in the Court of Criminal Appeal. I particularly recall the difficult matter of Hughes v R. His Honour’s careful analysis of law to a complicated factual situation was a masterpiece of the exercise of the judicial function.

The humanity at his personal core is threaded through Judge Zahra’s work and life. His humility and combination of personal qualities meant that his enormous legal skill and intellect was accessible to those who needed wise counsel. While he never courted publicity – as Judge Haesler says, he did plenty of high-profile cases but it was never his profile – the vast body of St Mary’s Cathedral was all but filled at his funeral. No small feat, remarks Justice Bellew, and ‘the only conclusion you can draw is that everybody who went knew him in a personal sense’. They knew him because of the moments he took, every day, for those around him. His deep sense of decency was a great enhancement to the system of justice which he administered and all those who work or are otherwise brought within it.

My respect for Judge Zahra’s intellectual ability, his integrity and capacity to deal with issues in a common-sense way resulted in his selection as Acting Chief Judge when I was absent.Judge Zahra was often asked to preside in difficult cases. He never declined to accept a case as he relished the challenge. He was an exemplary judge.His generosity of spirit, sense of humour and humility will be greatly missed by all the judges of the court. The Honourable Justice D M Price AO, Chief Judge of the District Court

By Ann Bonnor