- Winter 2023

- Sydney’s Missing Cycleway Network: A Strategic Policy Failure

Decades of car-centric city planning has come at an enormous environmental, economic and public health cost. In recognition of this, cities around the world are investing heavily in redesigning streets to encourage a shift away from private cars, including by building safe cycling infrastructure separated from traffic. Despite the recognised need to do so in Sydney, progress has been stymied by a lack of state government leadership, producing a patchwork of disconnected cycleways. This failure must be urgently addressed as part of the NSW government’s commitment to action on climate change.

The costs of Sydney’s motoring addiction

Sydney has been dominated by car-centric transport planning since the dramatic destruction of its tram network, one of the largest in the world, in the 1950s. The scale of the issues that this has caused are set out in a recent report by the Climate Council.1 Private motor vehicles now account for 68% of weekday trips by Sydney residents. The transport sector is the second-highest and fastest-growing source of greenhouse emissions in NSW, contributing 20% of total emissions, a majority of which come from cars and light commercial vehicles. Transport emissions were 50% higher in 2018–2019 than in 1990, due in part to a dramatic increase in the sale of SUVs. Passenger cars in Australia, with no fuel efficiency standards, emit 40% more carbon than the EU, 20% more than the US and 15% more than New Zealand.

The problem cannot be solved by a transition to electric vehicles alone. Conversion of the national fleet will take decades. EVs also generate significant lifecycles emission through their manufacture and disposal. Indeed, their operation may generate more greenhouse emissions than modern petrol cars while the power grid remains dominated by fossil fuel generation.

Other costs of car-dependency will not be solved by EVs: the annualised cost of road congestion in Sydney and surrounds is estimated by Infrastructure Australia to grow from $8bn in 2016 to $15.7bn by 2031. Road trauma is a significant cause of serious injury and death in NSW, and the leading cause of death in children aged 1 to 14. There is growing concern about the health impacts of exposure to non-exhaust particle emissions,2 and from physical inactivity. Seventy per cent of children are failing to meet minimum physical activity recommendations,3 and rates of active travel to school have dropped from 75% to 25% per cent of trips over the past 40 years.

A global shift away from cars

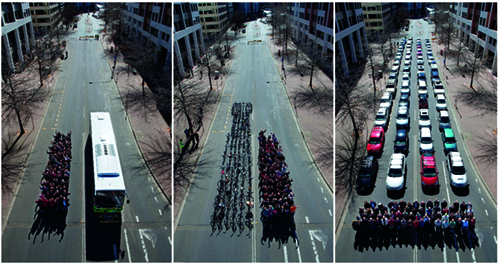

Against that backdrop, cities around the world are investing heavily in safe cycling infrastructure to encourage a ‘mode shift’ away from private cars. Commuting by bike is often the quickest form of transport for trips of up to 10km, is a far more efficient use of road space and carries with it the many benefits of incidental exercise. The rapid growth of e-bikes also makes cycling a more practical form of transport for a wider range of people, over greater distances, in hillier cities and with cargo or children on board.

In London, 260km of safe cycle routes were delivered in the five years to 2021, with cyclists now outnumbering motorists in the City of London. The Parisian government invested €150 million in cycleways between 2015 and 2020, and between 2021 and 2026 plans to invest a further €250 million and build 180km of separated cycleways. It will ban non-essential through-traffic from the Paris city centre by 2024. By 2018, New York City had built 770km of protected bike lanes as part of an initiative begun in 2007. Closer to home, in 2022 Wellington approved a NZ$334 million project to build a 166km cycleway network over ten years.

There is growing public demand4 and an obvious need for similar action in Sydney, with over two million car trips per day of less than 2km, and more than half of inner Sydney residents saying they would ride a bike to work once a week if cycleways were separated from traffic.5

The disappearing Principal Bike Network

Transport for NSW (TfNSW) is the obvious agency to drive the development a Sydney-wide cycleway network, as it retains a tight grip on the regulation of traffic on all public roads in NSW despite the conditional delegation of limited powers to local councils.6 However, in 2021 it quietly abandoned over a decade’s work towards the development of a ‘Principal Bike Network’ (PBN) – which included a 284km network of cycleways within 10km of the Sydney CBD.

That work, commenced in 2009 by the City of Sydney (CoS) (a leader in this area) and fourteen other inner-Sydney councils, was identified as a nationally significant priority initiative by Infrastructure Australia and therefore a candidate for federal funding. It became part of TfNSW’s 2018 ‘Future Transport Strategy 2056’, and involved the identification of specific routes to be funded by TfNSW. However, its development soon became shrouded in secrecy.7 By September 2021, it had been abandoned entirely and was then removed from the Infrastructure Australia priority list. In its place, TfNSW announced a series of ‘strategic cycleway corridors’ which are lacking in meaningful detail, including as to specific routes, timing and funding commitments.

The status quo: a fragmented patchwork of orphaned infrastructure

In the absence of any overarching strategy, a patchwork of fragmented cycleways has developed that does little to encourage more people to ride, and leaves those who try at best, confused and at worst, afraid, when cycleways abruptly end and they are forced to mix with traffic. Each section largely falls to be delivered by local councils obtaining individual grants, a cumbersome and time-consuming process subject to the whims of local and state political priorities. It is an approach that treats cycleways as novelty projects, rather than an important part of the state’s transport infrastructure. The main ‘Get NSW Active’ grant scheme will deliver just $50m state-wide in 2023–2024, a derisory portion of TfNSW’s $19 billion annual transport project budget.

The inadequacy of this approach is aptly illustrated by considering the development of a long-proposed cycleway route that would take a rider safely from Phillip Street to Bondi Beach. A cycleway along College Street was built in 2010 at a cost of $5 million, removed in 2015 at the instigation of then Roads Minister Duncan Gay, before being rebuilt and reopened earlier this year. It remains disconnected at each end. CoS is due to commence construction later this year on a cycleway (first proposed in 2020) along Oxford Street, but only as far as Taylor Square. The next section of Oxford Street, between Taylor Square and the Paddington Gates of Centennial Park, is a state road subject to a separate proposal by TfNSW with no clear construction timeframe. A cycleway between the Paddington Gates and the Woollahra Gates was built in 2014 by a different state body, the Centennial Park and Moore Park Trust. Bizarrely, in 2019 construction of that section became an election commitment of the state government despite having already existed for half a decade.8 It took over eight years for the subsequent section through Bondi Junction to be built by Waverley Council; first proposed in November 2014 and opened in March 2023. There is no clear plan to connect Bondi Junction to Bondi Beach (or elsewhere), a process complicated by the optimal and obvious routes involving roads controlled by different entities – TfNSW, Woollahra and Waverley Councils.

The failure to build a proposed ‘Beach to Bay Cycleway’ between Bondi Beach (Waverley Council) and Rose Bay (Woollahra Council) also illustrates the difficulty of building routes across council boundaries. First proposed in 2017, its construction as a ‘pop-up’ cycleway was announced (with fanfare) in 2020, but was subsequently abandoned by Woollahra in 2021 due to ‘concerns over parking loss’9. With Waverley continuing to progress its proposal, but Woollahra’s position unclear, the ‘Beach to Bay’ cycleway is liable to end up as a ‘Beach to Boundary’ cycleway instead.

Combating ‘Bikelash’

Attempting to develop a network in this haphazard way, divorced from any broader strategic context, leaves projects particularly susceptible to ‘bikelash’. As the architects of New York’s initiatives have observed, ‘[f]rom Milan to London, from Sydney to Vancouver, reallocating public space from motor vehicles for people to walk and cycle will inevitably send some residents into paroxysms of anger’ despite such proposals enjoying popular support.10 Fear of vocal opposition appears to dominate local council decision-making in particular. For example, despite Waverley having a detailed and considered policy commitment to prioritising pedestrians and bicycles over private vehicles, in practice the preservation of street parking is considered politically sacrosanct and severely restricts the ability to reconfigure streets. That is despite surveys consistently showing over 70% support for cycleway projects.11

Opposition to cycling infrastructure can emerge from unexpected quarters. The ‘Paddington Greenway’, a 2.2km pedestrian and cycle path between Centennial Park and Rushcutters Bay Park along Rushcutters Creek, was conceived by UTS students, supported by councils and the state government, and developed with $300,000 of public funding. It was abandoned by Woollahra Council in February 2023 after the Hakoah Club and Sydney Grammar raised safety concerns, the latter engaging child safety experts who opined that the route would ‘create the risk of opportunistic offending, which could include offensive behaviour, exhibitionism, masturbation as well as attempts to access children directly’.12 Nearby, Venues NSW and Rugby Australia recently joined calls for a pop-up cycleway along Moore Park Road to be removed, despite the Sydney Football Stadium redevelopment including a ‘Green Travel Plan’ with the objective of reducing car dependency and encouraging sustainable modes of transport.

Business as usual?

With schools and sporting bodies campaigning against cycleways, despite their obvious health benefits, the need for a step-up in state government leadership is manifest but has not yet materialised. While the current Transport Minister stridently criticised the previous government for failing to progress the PBN,13 the new government has not committed to reviving it. There are a range of other measures that would also improve the environment for cycling in Sydney, such as a review of draconian and selectively enforced fines for minor cycling offences, greater education and enforcement of minimum passing distance laws, lower speed limits on local streets, enforceable obligations to embed active transport improvements in major works, and congestion charging to reduce traffic volumes in the Sydney CBD. Such steps are necessary if the urgent need to address climate change is to move beyond rhetoric into practical action. BN

ENDNOTES

1 Climate Council Shifting Gear: the Path to Cleaner Transport 22 May 2023 at 11 https://www.climatecouncil.org.... See NSW specific data at NSW State of Environment, Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Transport https://www.soe.epa.nsw.gov. au/all-themes.

2 OECD Non-exhaust Particulate Emissions from Road Transport – Highlights 2020 https://www.oecd.org/env/highlights-non-exhaust-particulate-emissionsfrom-road-transport.pdf

3 Lindberg, R et al, Australian Health Policy Collaboration, Victoria University Melbourne Getting Australia’s Health on Track 2016 at p 14.

4 Better Streets Coalition https://www.betterstreets.info/

5 TfNSW Sydney’s Cycling Future: Cycling for everyday transport at p 7. <a href="

6" class="redactor-autoparser-object">www.transport.nsw.gov.au/sites... See TfNSW Delegations and traffic committees https:// www.transport.nsw.gov.au/opera.../ committees-communities-and-groups/ committees-and-groups/delegations; s 115(2) Roads Act 1993 (NSW).

7 See e.g., Parliament of NSW Question and Answer Tracking Details 5856 – Principal Bike Network https://www.parliament.nsw.gov... details.aspx?pk=86447; Alex Greenwich MP Principal Bike Network (letter to Minister for Transport and Roads) 15 September 2021 https://bicyclensw.org. au/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Principal-Bicycle- Network-REP-210915.rbl_.pdf

8 E Han, Sydney Morning Herald ‘New cycleway for eastern suburbs as govt doubles bike, walking paths spend,’ 2 March 2019 https://www.smh.com.au/politics/nsw/new-cycleway-for-eastern-suburbs-asgovt-doubles-bike-walking-paths-spend-20190301-p5116n.html

9 TfNSW Pop-up transport 6 February 2023 https://www.transport.nsw.gov....

10 J Sadik-Khan and S Solomonow, The Guardian ‘The bikelash paradox: how cycle lanes enrage some but winvotes’ https://www.theguardian.com/environment/bike-blog/2021/oct/29/the-bikelash-paradox-howcycle-lanes-enrage-some-but-win-votes

11 CoS Engagement Report – Cycleway and trafficimprovements on King Street, Sydney https://meetings.cityofsydney.... p 3.

12 Ibid.

13 Jo Haylen MP Treasurer has NSW spinning its wheels on active transport 27 November 2020 https://www.johaylen.com/treas...hasnsw_