- Winter 2023

- Prosecuting and punishing protesters: a hard bargain

Prosecuting and punishing protesters: a hard bargain

The history of progress in Australia – for the rights of Aboriginal people, women, asylum seekers and refugees, and the LGBTQ community, against racism, for peace, and for protection of the environment – demonstrates the crucial role that public protest, including civil disobedience, has played in creating social change and reform. All of these movements have been spurred on throughout the arc of history by prototypical political demonstrations where roads or other public spaces were occupied, including in defiance of laws and police directions.

Progress is usually hard-fought. As Clive Hamilton wrote in his seminal work What Do We Want: The Story of Protest in Australia: ‘Progress does not just happen, as if we are magnetically drawn towards some social utopia. It occurs because a few individuals begin to demand change. They must suffer, because those opposed to change are more powerful… as the demands become more insistent and the movement grows, the authorities may respond with draconian laws, imprisonment and beatings’.1

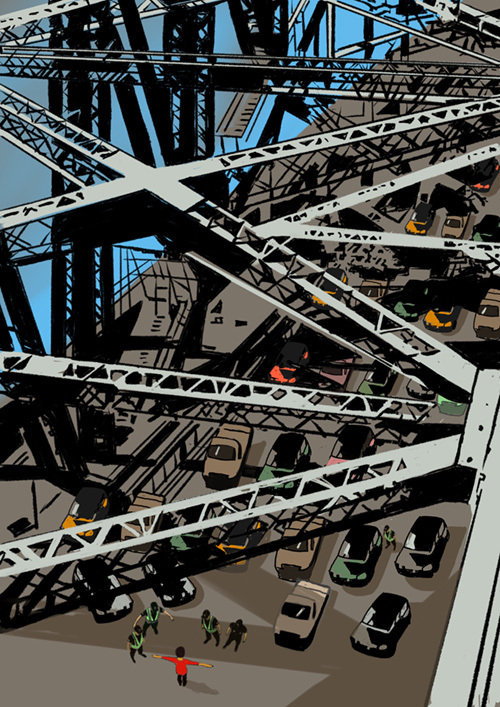

On 13 April 2022, four protesters parked two trucks in a lane on the Harbour Bridge in morning peak hour as part of an environmental protest against climate inaction ahead of the federal election. Two of them sat in front of the trucks and glued their hands to the road. Two of them climbed on top of the second truck and let off orange smoke distress signal flares. They livestreamed their action saying, ‘I can tell you, we don’t want to do what we are having to do today. It’s unpleasant, it’s painful, but unfortunately it has to be done because we are not getting the action that’s required. We need everyone who’s watching this to start acting as well. We need you to get out and say ‘Help! There is a climate emergency.’… None of us want to be here and doing this, but there’s no other way we can make the point. We’re desperate to make the point. We really need to do something urgently.… And I apologise on behalf of Fireproof Australia, for the inconvenience we are causing to Sydney motorists at the moment here on the Harbour Bridge, but there’s not much we can do. We’ve got to ask them to put up with this. Like they’re putting up with the dramatic problems [caused] by climate change.’ They were arrested and variously charged with offences, including entering the Sydney Harbour Bridge and seriously disrupting or obstructing vehicles attempting to use the bridge, contrary to s 144G(1)(b) Roads Act 1993 (NSW) which has a maximum penalty of a fine of $22,000 or imprisonment for 2 years or both. Police investigators drafted the ‘Facts Sheet’ which included in each case the statement that ‘the imposition on traffic prevented an ambulance responding to an emergency under lights and sirens as it was unable to navigate through the increased heavy traffic. This imposition to a critical emergency has the potential implication of loss of life.’ This was false in its entirety. There was no ambulance.

The protesters were refused bail by police, held overnight in custody, including expressly on the basis that the nature and seriousness of the offences on account of the obstruction of an ambulance warranted bail being refused. Consequently they were transferred into Corrective Services custody and strip searched. Police also required the protesters to undergo forensic procedures to obtain their DNA, including by force, despite their identities being known and their actions being squarely captured on video. Once released on bail by the court they faced stringent bail conditions, including house arrest, place restrictions, and broad non association restrictions prohibiting contact with other members of their political group concerned about the climate crisis.

In June 2022, the officer-in-charge signed a statement stating in clear terms that the protesters’ actions had blocked an ambulance from accessing the bridge and that his inquiries had demonstrated that. But they did not. The document he attached purportedly in support demonstrated that there was no ambulance. The true state of affairs was not conceded by police until it was too late for some.

The protesters all pleaded guilty to at least one charge in the Local Court. Two of them– Mr Jay Larbalestier and Ms Violet Coco – were sentenced on the basis of the false fact that the imposition on traffic prevented an ambulance responding to an emergency. Mr Larbalestier spent four days in custody and 42 days on house arrest before being sentenced by Magistrate Daniel Covington in July 2022 to a term of imprisonment for eight months to be served by way of an intensive corrections order, with 99 hours of community service and a fine of $1500. On strict bail conditions, Ms Coco had been in quasi-custody for almost three months by the time of sentence. Magistrate Alison Hawkins sentenced Ms Coco to an aggregate sentence of imprisonment for 15 months with a non-parole period of eight months and a fine of $2500. In sentencing Ms Coco, her Honour stated, ‘You have deliberately engaged in a form of protest designed and coordinated to cause maximum disruption to the community. There needs to be, in sentencing you for these offences, a significant element of deterrence to both you and others like you who would seek to pursue your political ends by causing the most significant level of disruption to the community that you can. … You knew this was illegal. You knew you would be arrested. … But what you have failed to take into account in the actions of stopping people going about their everyday life, is other people’s mental health concerns, or other people’s health and safety. You have halted an ambulance under lights and siren. What about the person in there? What about that person and their family? What are they to think of you and your cause? In fact, you do damage to your cause when you do childish stunts and dangerous stunts like this. It angers the community and rightfully so. … Your actions deserve condemnation from not only the courts but the community because by illegally protesting in the manner you have done in the deliberate and planned manner to gain maximum exposure while livestreaming and while putting off a flare, you caused a significant level of distress to the community which ultimately would undermine whatever cause that you are hoping to pursue in that end. So the principles of deterrence loom large in relation to this.’ Ms Coco immediately filed an appeal against the severity of the sentence to the District Court, however her Honour refused bail on the appeal, and she remained in prison until she was subsequently granted bail by the District Court 12 days later.

The two other activists – Alan Glover, a 61-year-old man and honoured firefighter, and Karen Fitzgibbon, a 45-year-old mother– had initially pleaded not guilty. Mr Glover had disputed the assertion about the ambulance being obstructed from the outset of his proceedings, and as a result obtained a copy of the brief of evidence with the NSW Ambulance records that revealed the true picture – there was no ambulance dispatched at all. The police belatedly acknowledged the falsehood at the sentence hearing for Mr Glover and Ms Fitzgibbon in early March 2023. In sentencing these two offenders, Magistrate Daniel Reiss stated that notwithstanding some fairly strong subjective factors for each of the offenders, there were a number of things that might have tipped the balance to a custodial outcome, and that the cases were more at that end of the sentencing scale. Both receiving convictions for the first time, they were sentenced by his Honour to community corrections orders for 18 months and fines of $3000.

As stated by Laws LJ in Tabernacle v Secretary of State for Defence [2009] EWCA Civ 23, ‘[r]ights worth having are unruly things’.2 Free speech as exemplified by public political gatherings is ‘a hallmark of a democratic society’3. It is not equivalent to protest by social media. Rather, ‘[d]emonstrations in public spaces remain a powerful method of advancing particular causes to governments and the general community, as well as engendering a feeling of solidarity among participants and those associated with them who may be unable to be present’.4 Further, ‘[a] peaceful demonstration or protest, whether by assembly or procession in a street, is nowadays accepted by members of the community as a safety valve for the community and potentially at least as an agent for change and for the good. An ordinary incident of any assembly or procession through the streets is some inconvenience to others’.5

The legitimate democratic right to protest conferred on all Australian citizens as an incident of the implied freedom of political communication is ‘not unfettered’. It does not authorise unlawful acts.6 Society may expect that protest against policies and action of governments will be made only by lawful means, and it is the duty of courts to uphold the authority of the law in that regard.7 But ‘peaceable protests are to be tolerated in recognition of the freedom of others to hold different opinions, to speak, to assemble, and to associate’; and ‘[i]t is only the unreasonable use of a highway for the purpose of protest, whether by assembly or procession, which is unlawful.’8

When unlawful acts of protest are committed and prosecuted it is left to the courts to determine the appropriate outcome. Courts, at least in the UK and Europe, have traditionally accepted that where offending is a form of non-violent protest against activities to which an accused strongly objects, that is a contextual factor of some importance on sentence,9 including in assessing culpability.10

While courts are reluctant to adjudicate, even impliedly, on the merits of the issue that is the subject of the protest during which the offence was committed, it is well established that nonviolent crimes committed in the course of peaceful protest do not give rise to high levels of culpability.11

Further, as stated in R v Jones (Margaret) [2007] 1 AC 161 at [89]:

My Lords, civil disobedience on conscientious grounds has a long and honourable history in this country. People who break the law to affirm their belief in the injustice of a law or government action are sometimes vindicated by history. The suffragettes are an example which comes immediately to mind. It is the mark of a civilised community that it can accommodate protests and demonstrations of this kind. But there are conventions which are generally accepted by the law-breakers on one side and the law-enforcers on the other. The protesters behave with a sense of proportion and do not cause excessive damage or inconvenience. And they vouch the sincerity of their beliefs by accepting the penalties imposed by the law. The police and prosecutors, on the other hand, behave with restraint and the magistrates impose sentences which take the conscientious motives of the protesters into account. The conditional discharges ordered by the magistrates in the cases which came before them exemplifies their sensitivity to these conventions.

Thus, there is a bargain struck: the protester avoids excessive damage or inconvenience, and this is matched by a restrained approach by police and prosecutors and by the courts in sentencing.

Free speech in the UK is a qualified right whereby freedom of speech and freedom of assembly are guaranteed by articles 10 and 11 of the ECHR subject to such restrictions as are prescribed by law and are necessary ‘in a democratic society’ for the prevention of crime.12 In this context the Strasbourg Court has considered the proportionality of sentences imposed for crimes committed in the course of peaceful protest.13

The principles were set out in Taranenko v Russia (App. No. 19554/05). That case concerned events in 2004 when a group of protesters forced their way into a building used by Vladimir Putin and barricaded themselves in a room on the ground floor. Once inside they waved anti-Putin placards, threw leaflets and chanted slogans calling for his resignation. They stayed for an hour and damaged some property. The applicant was remanded in custody. She was convicted of criminal damage and participation in mass disorder. After a year in custody, she received a suspended sentence of imprisonment of three years.

The Strasbourg Court reviewed its case law on sentencing protesters ‘which reveals that the Contracting States’ discretion in punishing illegal conduct intertwined with expression or association, although wide, is not unlimited. It goes hand in hand with European supervision by the court, whose task is to give a final ruling on whether the penalty was compatible with Article 10 or 11. The court must examine with particular scrutiny the cases where sanctions imposed by the national authorities for non-violent conduct involve a prison sentence’.14

The court went on to characterise the anti- Putin protest as ‘involving a certain degree of disturbance and causing some damage’ but that it ‘did not amount to violence’.15 It held that the circumstances of the offence did not justify being remanded in custody for a year, followed by a suspended sentence.16 That is, the sentence imposed was not proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued by the protester.17 The court held that there had been a violation of Article 10 interpreted in light of Article 11 and that the ‘unusually severe sanction imposed… must have had a chilling effect on the applicant and other persons taking part in protest actions’.18

Where disruption caused by protest is the intended aim and not a side-effect of a protest held in a public place, conscientious motives will not insulate a person from the sanction of imprisonment.19 However, courts should still be reluctant to impose immediate custodial sentences for peaceful protest,20 even where the action is deliberately disruptive. The acts remain to be properly characterised as acts of civil disobedience, from which three things flow:21

1. Assuming the protester eschews violence and shows some measure of moderation in the level of harm intended, the protester establishes a moral difference between themselves and ordinary lawbreakers.

2. By reason of that difference, the protester is generally a law-abiding citizen, such that less severe punishment is necessary to deter them from further law-breaking.

3. Part of the purpose of imposing sanctions is to engage in a dialogue with the defendant so that he or she appreciates the reasons why in a democratic society it is the duty of responsible citizens to obey the law and respect the rights of others, even where the law or other people’s lawful activities are contrary to the protester’s own moral convictions. Such a dialogue is more likely to be effective where authorities (including judicial authorities) show restraint in anticipation that the defendant will respond by desisting from further breaches.

The sentencing of offenders charged with offences arising out of protest activities has received relatively limited judicial attention in Australia. However, consistent with the approach taken in the UK, it has been accepted that:

Acknowledging that there is a legitimate right conferred on all Australian citizens to protest enshrined under Australian law, there inevitably needs to be a careful balancing of sentencing considerations including deterrence and denunciation on the one hand, with the right of all citizens to engage in legitimate protest actions on the other, when sentencing offenders for offences committed in the course of protest actions.22

And further that:

[W]hilst offending committed in the course of a peaceful protest would not generally impute a high level of culpability, and while the conscientious motives of protesters are to be taken into account, whether the protesters have behaved with a sense of proportion by not causing excessive loss, damage or inconvenience by their protest actions will be an important consideration in assessing the objective seriousness of the offending and the culpability of the offenders involved.23

In these ways, ‘the value of the right to freedom of expression finds its voice in the approach to sentencing’.24

On 15 March 2023, Ms Coco’s appeal against the severity of sentence was heard by his Honour Judge M Williams SC together with an appeal against the severity of sentence brought by Mr Glover.

His Honour found that the video footage of the event tendered by the Crown on the appeal showed vehicles moving in other lanes both north- and south-bound in a way not dissimilar to conventional peak-hour traffic. His Honour acknowledged the restraint by the protesters in only blocking one lane of the bridge. His Honour rejected the Crown’s submissions that the offenders or their actions could be characterised as dangerous to the community. His Honour accepted that the protesters had compelling subjective cases.

His Honour set aside the orders of the Magistrates in both cases and sentenced Mr Glover to a conditional release order for 12 months without conviction; and notwithstanding her history of offending during protest activities in NSW, the ACT and Victoria, his Honour sentenced Ms Coco to a conditional release order for 12 months with conviction. As Mr Glover said in unchallenged evidence:

I did not want to take this action and cause disruption to the Sydney community however, given the lack of climate action by successive governments and by corporations, I felt I had no other choice. I felt desperate. My motivation for participating in a public protest to temporarily block a lane of the Sydney Harbour Bridge was to draw the community’s attention to, and raise awareness about, the climate crisis and to bring about some action – some immediate action by the government in relation to our specific demands. I chose the Harbour Bridge because of its high visibility and symbolic significance to the community, and because we knew we could block one lane and allow traffic to move around us using the other five lanes available at the time.

Many successful social movements throughout history have used ‘non-violent disruptive actions to draw attention to their cause; actions that at the time were decried by the majority as extreme and counterproductive, but through the filter of history are now seen as necessary and worthy’.25 If protesters continue to adhere to their side of the bargain, the challenge for courts is to strike the right balance on sentence in the face of a growing sense of desperation and urgency among the citizenry about the climate and other injustices. BN

ENDNOTES

* Felicity Graham is a barrister at Black Chambers. She appeared for Alan Glover in the proceedings in the Local and District Courts referred to in this article.

1 Canberra: National Library of Australia Publishing, 2016 at vii.

2 At [43].

3 Commissioner of Police v Gray [2020] NSWSC 867 per Adamson J, as her Honour was then, at [59].

4 Gray at [59].

5 Watson v Trenerry (1998) 122 NTR 1 per Angel J at 7.

6 EH v QPS; GS v QPS [2020] QDC 205 at [71].

7 Carlson v Hayward (Unreported, Supreme Court of the Northern Territory, Kearney J, 26 April 1996).

8 Watson v Trenerry at 7-8.

9 Cuadrilla Bowland Ltd & Ors v Lawrie & Ors [2020] EWCA Civ 9 at [40].

10 Cuadrilla Bowland at [87].

11 R v Roberts [2018] EWCA Crim 2739 at [32].

12 Roberts at [38].

13 Roberts at [39].

14 At [87].

15 At [93].

16 At [94].

17 At [95].

18 At [95]-[97].

19 Cuadrilla Bowland at [94]-[95].

20 Roberts at [43].

21 Cuadrilla Bowland at [96]-[98].

22 Avery & Ors v Queensland Police Service [2019] QDC

21 at [78]-[79], referring to the decision of Olsson J in Brock v SA Police; Forrester v SA Police (Unreported, Supreme Court of South Australia – Magistrates Appeal, 18 August 1993); EH at [71].

23 Avery at [81]; EH at [72].

24 Roberts at [34].

25 Lancet Journal of Planetary Health, Editorial, ‘A role for provocative protest,’ Vol 6, Issue 11, November 2022.