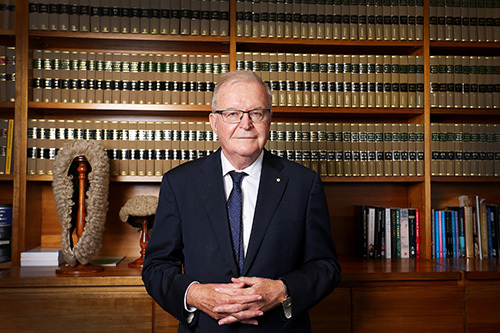

On 4 February 2022, Naomi Wootton of Bar News spoke in chambers with the Honourable Tom Bathurst AC, chief justice of New South Wales, who retired from judicial office on 5 March 2022.

The chief justice reflected on the eleven years he has spent as the state’s seventeenth chief justice.

Bar News (BN): Good afternoon, chief justice. Thank you for humouring us one last time. It has been eleven years. Was it different to what you expected when you took the job?

The Hon TF Bathurst AC (HTB): Yes. I did not realise the amount of administration which was involved. I rather thought that I could spend about one third of my time on the administration and two thirds on judging. That was just impossible: it ended up being about fifty-fifty.

BN: You have also been lieutenant-governor of the State of New South Wales for the past 11 years. What was that like?

HTB: It was fun. Seeing how the Executive Council works is interesting. While I could never do the job all the time (I’m not pleasant enough) it frequently gave me the opportunity to meet a broad cross-section of the community, and that I did enjoy.

BN: What has been the biggest change you have seen in your time: in the court, or in practice more generally?

HTB: The biggest change has been forced on us by the pandemic, and it is the wholesale adoption of technology in the court. Both judges and the profession are now used to the idea that you don’t have to come to court to get things done. The pandemic also encouraged the state government to spend money on upgrades, which they are continuing to do. We have just completed a large-scale technological upgrade of the Banco Court – great for my successor, not for me. It has better screens, sound, video facilities. And the little things have been fixed. It used to be the case you could only see one judge on the bench clearly, now you can see all three with much clearer focus. One of the complaints that came from the Bar was that they couldn’t work out what the other two judges were thinking …

The ideal advocacy combines the written and oral aspects well.

BN: Bret Walker SC was quoted recently in the AFR saying that he wants to be back in the (physical) courtroom. Do you agree or disagree with that sentiment?

HTB: I think the hybrid models are going to be with us forever. But there are some cases which are plainly better with a live hearing. For example, when there are difficulties with interpreters and difficulties where people do not have sophisticated web connections or technological facilities themselves. I understand what Bret was saying, both sides of the Bar table miss the interaction between the Bench and Bar. You experience this at the appellate level as much as at first instance. But there is also no reason for someone to come from outer western Sydney or beyond to send up consent orders, and limited contested hearings can and should be done online.

BN: What have you found the most challenging?

HTB: There were different challenges at different times. When I first came in, I was dealing with judges I didn’t know, and fields of the law I knew nothing about. The first time I sat on the Court of Criminal Appeal, everyone started talking about Rule 4. I had no clue what they were talking about. It was certainly awkward, as presiding judge. The upheavals over the past few years have been challenging — we had the flood, and the pandemic — which came with organisational challenges. The judges have been terrific throughout it all.

BN: … and the most enjoyable?

HTB: The intellectual challenge in dealing with a wide range of areas is enjoyable. Parts of the administration are enjoyable. Some of it is frustrating but not all of it, particularly when you see some progress. What I really have enjoyed is the collegiality of the court. You don’t really know what happens on this side of the court building until you get here. I was apprehensive but I was pleasantly surprised.

BN: Before you came to the bench you had not done a lot of crime. You have now sat on some of the most important cases that have been through the Court of Criminal Appeal in the last ten years. How did you find that?

HTB: Well, I dabbled in criminal law in my first few years at the Bar. I won’t say how long ago, people can work that out. It was a steep learning curve, on three levels. First, familiarising yourself with the underlying legal principles, some of which are complex. Secondly, understanding the procedural rules both governing trials because you need to know them for appeals, and governing appeals. Thirdly, the most difficult thing, as far as the Court of Criminal Appeal is concerned, was appreciating what was or was not an appropriate sentence, when you have not done one for many years.

BN: Do you harbour any regret that you were never a trial judge?

HTB: I don’t regret that I was never a trial judge only doing trials. I do regret not sitting on trials from time to time. One thing I have been pleased about is that judges of appeal are commonly doing that now. Because administrative matters can crop up on fairly short notice in this job, it was impractical for me to do a trial of any length.

BN: As well as a jurist you are in many ways a manager, but of a very unique kind. You ‘manage’ some 50 or so other independent judicial officers vested with independent judicial power. How is that role?

HTB: It is important to try and lead by example. Obviously, you do not interfere with any other judge’s exercise of judicial power. You would never suggest to a judge that they should decide a case in a particular way. You also lead by encouragement. If the judge respects, you then I think that can go a long way.

If they don’t, I don’t know (I hope they respected me). One thing I think is very important is that it is a collegiate role. It is most important to talk to other judges, to see what their concerns are. Throughout the pandemic we had a series of judges meeting on a regular basis, via AVL.

BN: What did you learn from being a judge that you wish you had known as a barrister?

HTB: The benefit of good written submissions.

BN: What will you miss the least?

HTB: Submissions which refer to every case on the topic when one High Court case has conclusively dealt with things.

BN: How important do you think oral advocacy is? How often does it really make a difference?

HTB: Quite often. Particularly in difficult cases. There have been a number of occasions where having read the written subs carefully you form a preliminary view and that is changed. Other cases you form an uncertain preliminary view, which firms up as a result of oral advocacy. The ideal advocacy combines the written and oral aspects well.

BN: What was the most irritating thing that counsel did?

HTB: Counsel who had ten points, one of which was excellent, nine of which were hopeless, and then they spent their whole time arguing the nine hopeless ones and saying nothing about the tenth.

BN: Did you have any tricks to control getting irritated at counsel?

HTB: I’m told that when I was irritated, I used to hit my hand against my knee from time to time. But I tried not to get irritated. I don’t say I always succeeded.

BN: Were you rolled by the High Court often?

HTB: No.

(Laughter).

BN: When it did happen, did you feel annoyed?

HTB: No. Law is not a science. Different people have different views.

BN: Is there a case you are the most proud of? Or a case that is particularly memorable?

HTB: No, I don’t think so. The real challenge was to get judgments out in a timely fashion. I can remember some cases where I thought the advocacy was absolutely outstanding, and they are memorable for that reason. Some cases were memorable for the human tragedy which lay behind them. Other cases had particular scientific challenges. Just like the Bar, I came across a huge variety of different areas.

BN: What would you describe as the defining moment of your judicial career?

HTB: There was no defining moment in a strict sense. In a job like this you go through stages. The first is a learning curve. You do that for a considerable period of time. Then you get to the stage where you feel you are on top of it and feel you can implement some ideas and policies. Then, I think you get to a stage where – as with any chief executive – fresh ideas become necessary and desirable. And that is one of the reasons I am leaving now, and not in twelve months’ time.

BN:** Did you have much self-doubt? Or were you always confident in what you decided?

HTB: I always had self-doubt. When you don’t have it is when you get yourself into trouble.

BN: Is there anything you wish you had more time to do?

HTB: There are always ways you can improve a place. There is no radical reform that I would have liked to have done but haven’t.

There is a satisfaction in resolving disputes.

**BN: **Do you think the job changed you? As a person or lawyer?

HTB: It didn’t change me as a person, or as a lawyer, but I certainly acquired or tried to acquire some new legal skills. I think it reopened my eyes a little bit to problems in the community. When I was at the Bar, particularly in the last few years, I was practising in a fairly narrow area with a fairly limited group of people.

Doing this job exposed me to a whole lot of different problems, which members of the Bar, judges and most importantly litigants experience. It improved my appreciation of the stressors that some lawyers – particularly younger practitioners – are going through. We have direct contact with the tipstaves who you see on a day- to-day basis and then you keep in touch afterwards as they enter the profession.

Doing this job exposed me to a whole lot of different problems, which members of the Bar, judges and most importantly litigants experience.

BN: What is your fondest memory of your time on the court?

HTB: There is a satisfaction in resolving disputes. I thought I would never become a judge. When I was offered this role, I thought holistically, it would be a great challenge, which I wanted to take on. What surprised me is how much I came to enjoy the day-to-day function of judging over the years.

BN: What are you looking forward to the most about retirement?

HTB: Going back to a life where things aren’t quite as certain.

BN: What is your hope for the future of the court?

HTB: I not only hope, but know, that all of the judges and court staff will strive to improve the quality of the work done. I know there will be challenges in the future, what I don’t know is what they are. But I know that the morale and collegiality in the court will overcome them. My real hope is that whatever happens in the future, the court will remain the collegiate institution that it is and will work cooperatively to resolve difficulties that emerge from time to time. BN