- Winter 2024

- Interview with the Hon Chief Justice Debra Mortimer

Bar News (BN): Belated congratulations on your Honour’s appointment as chief justice of the Federal Court of Australia [in 2023]. As we are doing this interview remotely, I’d like to start by asking you to describe what I would see on your walls if I were there in your chambers in person.

Mortimer CJ: Right behind me you would see a wall of media images and clippings from cases I was involved in. These include M611, M702, the Palm Island Case3and the Brown Mountain Potoroo Case4 that I did with Richard Niall (now Niall JA).

One of the framed cuttings is from a fairly mainstream New Zealand news and current affairs publication called The New Zealand Listener. It says (referring to the Palm Island Case), ‘A Kiwi judge has exposed a racist police service and found justice for a wronged Aboriginal man’. It’s a parochial piece saying, in effect, that it took a New Zealander to do this.

The artwork is mostly from the Torres Strait, including carvings, and from Aotearoa New Zealand.

BN: In a 2010 interview, you told the Sydney Morning Herald that you were a New Zealand citizen and you were going to remain a New Zealander (and thus would be liable to deportation should the situation arise).5 Is that still the case?

Mortimer CJ: I am now a dual citizen and have been since shortly after I took the first appointment to the court. The process of obtaining Australian citizenship wasn’t any quicker for me than it was for anyone else. I do maintain close ties with Aotearoa New Zealand: what’s left of my extended family is in Aotearoa New Zealand, and I have a house there and spend quite a few weeks a year there. Keeping a connection with my Kiwi roots is very important to me.

BN: You have previously referred to a difference between New Zealand and Australia in the way the two countries acknowledge or engage with their First Nations histories. Do you still consider that to be the case?

Mortimer CJ: Yes. Although many Pākehā and Māori would say there is still a long way to go in that country, I think they are further ahead on the track of recognising their post-colonisation history and acknowledging the terrible parts of it. I believe Aotearoa New Zealand as a nation has a community life that is more inclusive, at all levels, of Māori and Pasifika cultures. They showcase to the world that if you are from Aotearoa New Zealand, then the Indigenous heritage, language and culture of that country is part of who you are. It is not ‘other’, in that sense.

Now I see that in a different way when we engage with judges from Aotearoa New Zealand. All the judges I have met can speak some Māori, and it’s expected that if they are giving any kind of public address they start with a mihi, which is an introduction of who they are, who their family is and where they are from. The Chief Justice of New Zealand speaks in Māori for considerable periods of time at the start of her speeches. Judges will go to a marae for traditional welcomes and speeches, and rituals, as part of conferences. There is a lot of engagement with Māori culture in ceremonies in New Zealand courts. New Zealand Supreme Court Justice Joe Williams, who was in Melbourne earlier this year, talked about that in some of the public speeches he gave here, specifically some of the rituals before an event commences.6 He also referred to singing, though I can’t imagine much singing happening in Australian courts for a while. We have a lot to learn about engaging with First Nations people and about how to substantially incorporate their views of the world, their Country and their culture into the life of our community as a whole and our lives as individuals.

BN: In your practice at the Bar and in your work as a judge, you have been involved in Indigenous legal issues, such as dealing with the Palm Island matter and land rights cases in the Northern Territory. Native title, which falls within the jurisdiction of the Federal Court, often involves going on Country when undertaking hearings or making consent orders; can you say something about the importance of being on Country?

Mortimer CJ: The first thing I would say would be to acknowledge [former Federal Court Chief Justice] Michael Black and some other[s] of the early judges who embraced alternative ways to hold hearings and take evidence. They were prepared to modify court processes to accommodate First Nations cultural protocols and practices and to try to ensure the court received the best evidence from witnesses where they were most comfortable talking about matters going to native title, which is generally on their Country. Those early judges carved out and created what is a unique feature of our court: on-Country hearings.

BN: When you were appointed chief justice in 2023,7 you had been a judge of the court for some 10 years.8How have you found the transition to the more managerial and policy-oriented aspects of the new role?

Mortimer CJ: One of the biggest challenges is fitting in court work, given the huge amount of administration and the number of reforms and initiatives we have underway about how the court does its work. To ensure I do some court work, I am doing at least one appeal per sittings and I’m doing some native title case management, interlocutory hearings and determinations in Cape York and the Torres Strait matters, as well as some appellate interlocutory work.

BN: Focusing for the moment on administration, are there any ideas or plans you have for how the work of the court might change or develop?

Mortimer CJ: My predecessor, Chief Justice James Allsop, had put a lot of energy into the court and its structures through the National Court Framework and the national practice area model, and I am committed to maintaining that. I also consider it important that the work of the court is evenly and fairly spread across all judges, so that judges in each practice area get to do both the challenging work and the more ordinary work and have a chance to develop and improve their skills and knowledge and their court craft. That includes dealing with high profile cases. I am also very committed to engaging closely and continuously with each individual judge on issues such as professional development and workload. That includes encouraging and supporting judges to be involved in internal and external facing activities outside their court work, such as presenting seminars and CPDs, engaging in international cooperation work with other courts in the Asia–Pacific region, and engag[ing] in court committees and project groups. This is so that our judges feel they are involved in driving reforms and initiatives within the court, where they affect how judges do their work.

There are 49 full-time judges – 50 including me – and something I implemented last year is annual registry visits, where I go around the entire country and have a session with every single judge, going through issues such as how they are managing their workload and practice areas, their ambitions or aspirations for how they can develop as judges, and what areas they’d like to work more in, as well as discussing the kinds of non-proceeding-related work I have described. The feedback I am getting is that it is very much appreciated. While it is time consuming and takes a lot of energy, it is a great way to get to know all of my colleagues. Those registry visits also provide an opportunity to engage with the local profession and with the registrars and court staff, particularly in the registries where we don’t have a permanent judge.

I am also very committed to international external-facing engagement with courts in the Asia–Pacific region and beyond. As a national court, our court is well placed to provide cooperation and assistance to other courts that are less well resourced than we are, and I intend to try to ensure that all the judges who want to be involved can do so and that we increase the work we do internationally. Encouraging and supporting judicial independence and the rule of law in this kind of work is important, but it is also important to use our experience in particular practice areas to assist regional courts to develop practice and procedures, mediation, and transformative practices such as digital court environments and records. Australian courts are fortunate, and we have much we can share with our judicial neighbours.

BN: During your time at the Bar and also in your time as a puisne judge of the court, you forged and maintained close links to the legal academy, teaching at both Monash and Melbourne law schools. Is that something you still do?

Mortimer CJ: I am co-teaching this year with [Laureate Professor Emeritus] Cheryl Saunders in the Masters program at Melbourne Law School in a course we are developing about comparative administrative law. I have found it harder to fit in teaching, but I am very much looking forward to getting back to it this year.

BN: In a paper published in the Melbourne University Law Review about judgment writing, you say that judges can do better and make written reasons for decision more accessible, shorter and more straightforward. 9 Is that something to which you continue to aspire?

Mortimer CJ: This is something that needs a collective approach, and our court is well suited to being an innovator as we do both trial and appellate work. Of course, developing a more efficient and effective approach to judgment writing – one that recognises the increasing demands on courts to get through their work and give parties outcomes – also depends upon at least some support from courts further up the appellate hierarchy. Judgments can tend to be defensive against appeals, which can be unhelpful to clear thinking and reasoning (and also to accessibility). I would certainly like to see much greater movement towards the function of reasons being to give explanations in accessible language about the orders made by the court rather than judges feeling they need to produce a scholarly piece.

Of course, I count myself as someone who has fallen into those traps. We are here to resolve disputes. There are some occasions where the law needs to be developed, clarified or reconciled in the reasons we write. However, I consider we can do better at recognising and permitting different categories of reasons for judgment, depending on the complexities of the issues of fact and law that are involved.

BN: Changing direction, a theme that emerges both from media reports and from the speeches at your welcome as Chief Justice is your history of caring for vulnerable people, particularly children. In her speech, the Vice President of the Victorian Bar Association, Elizabeth Bennett SC, said:10

Over the decades you have been a judge, you have been committed to the care of many children whose parents, for whatever reason, have not been able to care for them at the time and those children have brought you considerable joy and chaos.

Professor Saunders recalls one occasion when you were teaching law students about the importance of statutory construction while carrying a sleeping three-month-old.

And the media reports frequently refer to the two young boys from Kenya you were representing, who needed a guardian and a place to live; you took them home with you and then had to find them alternative representation.11 Is that something that you continue to do since you have taken on your current role?

Mortimer CJ: I have been a registered foster carer for more than a decade. I had always done a lot of either volunteering or pro bono work, though I have never been associated with any political party or been involved in any public campaigns of any kind. When you take an appointment, there are a whole lot of things you can’t do. But one thing I could do was to become a foster carer, in the state [Victorian] system. It takes some time to get qualified, and then I started doing respite care, although I ended up having full-time care of a baby who became a toddler. Since then, I’ve had a number of kids for respite.

As for the two Kenyan boys, that was a consequence of some litigation I was involved in as counsel. The narrative can be found in reported cases. When they were returned to Australia after being removed before their appeals had been dealt with, they were detained again and would have had to stay there if we couldn’t find them somewhere to go. Let’s just say getting them out of detention into a place the department would approve was a challenge. So I volunteered. I then, of course, stopped acting for them. They were around 15, and that was quite a commitment; they stayed with me for around a year while my children were primary school age, until we found them other places to live. It wasn’t just me on my own – there were a number of other lawyers and refugee advocates, including the Brigidine nuns in Melbourne, who were involved in their care once we got them out of detention.

BN: The swearing-in and welcome speeches refer to you in terms such as ‘legal rockstar’. It’s reported that you decided you wanted to be a lawyer when you were 14, and it’s well known that you had stellar academic success, an associateship with Justice Gerard Brennan on the High Court, and an enviable practice. Had you ever aspired to being a judge, or indeed, chief justice of the Federal Court?

Mortimer CJ: Becoming a judge had never been a lifelong ambition of mine. I loved the Bar; it was being a barrister that was my lifelong ambition. I was appointed a puisne judge after I’d been a silk for 10 years, at which time my children had finished school. I was ready to think about being a judge after 10 years as a silk. Being chief justice was not on my radar. These things occur through a combination of circumstances. You can’t really aim for a position like this. If it happens, it happens.

Being chief justice is administrative and managerial in many ways that aren’t visible as a puisne judge. I was quite surprised by the depth and breadth of the role, including the degree of external-facing commitments. I do want to be available to the legal and wider community, but if I said yes to every invitation, that would give me no time for other aspects of my role. There are probably an increased number of such invitations because I am the first female chief justice.

BN: On that, you are seen as a role model for women in the profession; do you see yourself as an advocate for women?

Mortimer CJ: I would see myself as advocating by example and by providing support and visibility, rather than by direct advocacy. It seems to me my appointment might be a signpost for not just women but people from a range of diverse backgrounds. Focusing on women, things are really different from when I signed the Bar Roll in 1989, but there are still persistent disparities in, for example, statistics about appearances and speaking roles in courts like ours. In considering these disparities, I believe you can’t ignore societal issues about how we structure our personal and family lives. Those issues are not necessarily capable of being solved within the profession. I still think there is work to do to break down some of those more traditional established networks as sources of how people get work in the profession. While there is a clear focus on gender, we don’t emphasise socioeconomic diversity enough in the legal profession and in the courts.

BN: We have referred to the Sydney Morning Herald piece headed ‘Rebel with a cause’; is that a label that you see as still fitting now that you are chief justice? And if so, what are your current cause(s) for the court?

Mortimer CJ: The ‘rebel’ label is probably quite true in some ways, as I am not a very good fit with a lot of the previous judicial leaders, but I have been fortunate enough to have a really good career, irrespective of my background.

As for causes: first, I continue to think we can do better in terms of the quality of resources and equal access to quality representation for people who have cases with merit. The second thing is that this court has an impressive reputation built up by my predecessors across so many different practice areas, so it is important to ensure that we continue to be a leader across all those practice areas. Obviously, with my background I would single out public law, industrial and employment law and native title law. Some of the more high-profile practice areas might be commercial law, intellectual property law or defamation law, but we have to be a court that showcases our expertise across all the areas of our practice. That quest for expertise requires us to recruit the very best practitioners in those areas, and I am committed to trying to achieve that.

BN: Last question: Is there any truth to the rumour that there are now compulsory judicial yoga classes every day?

Mortimer CJ: (laughs) There are voluntary yoga classes twice a week in Melbourne and weekly in Sydney and, I think, also in Perth. I’m not sure about the other registries. I do want to encourage all my colleagues to stay active, and that includes other things like riding bicycles to work or doing some form of exercise during the working day.

BN: Thanks for taking the time out of your busy schedule to talk to Bar News

ENDNOTES

1 Plaintiff M61/2010E v Commonwealth (2010) 243 CLR 319.

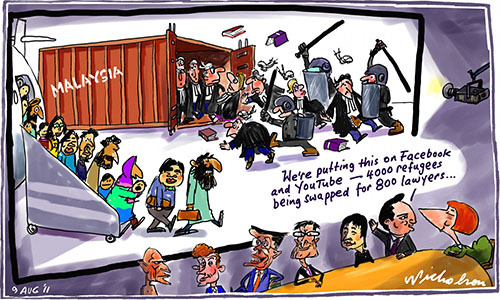

2 Plaintiff M70/2011 v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship (2011) 244 CLR 144.

3 Wotton v Queensland (No 5) (2016) 352 ALR 146.

4 Environment East Gippsland Inc v Vicforests [2010] VSC 335.

5 Michael Gordon, ‘Rebel with a cause’ Sydney Morning Herald (Web Page), 27 November 2010; <https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/celebrity/rebel-with-a-cause-20101126-18ar5.html >.

6 See ’In Conversation: From Treaty to Settlement, to Treaty Settlements: a conversation between Justice Joe Williams and Chief Justice Mortimer’ (YouTube, 4 April 2024) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5S4rPDcVWv4 >.

7 See Federal Court of Australia, ’Ceremonial Sitting of the Full Court to welcome the Honourable Chief Justice Mortimer‘, Federal Court of Australia (Web Page, 17 April 2023) <https://www.fedcourt.gov.au/digital-law-library/judges-speeches/justice-mortimer/mortimer-cj-20230417>.

8 See Federal Court of Australia, ’Ceremonial Sitting for the Swearing in and Welcome of the Honourable Justice Mortimer’, Federal Court of Australia (Web Page, 12 July 2013) <https://www.fedcourt.gov.au/digital-law-library/judges-speeches/justice-mortimer/mortimer-j-20130712>.

9 Debbie Mortimer, ‘Some Thoughts on Writing Judgments in, and for, Contemporary Australia’ (2018) 42 Melbourne University Law Review 274. (A version of this lecture was originally presented by the author as Melbourne University Law Review Annual Lecture, Melbourne Law School, 27 March 2018.)

10 Federal Court of Australia (n).

11 See Gordon (n 5).