- Autumn 2023

- Experienced Barristers Evening

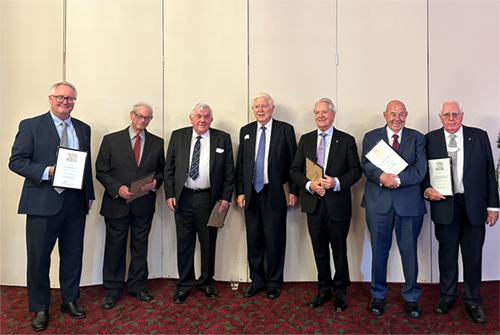

The following is an edited version of the speech delivered by The Hon Arthur Emmett AO KC at the NSW Bar Association Experienced Barristers Evening on the 17 February 2023 celebrating those who had practised as barristers in NSW for over 50 years.

The Bar and Roman antiquity have some interesting connections and I propose to mention some of these connections. First, might I advert to the enactment that first recognised the possibility of locally educated lawyers being admitted to the Bar.

Until 1848, only English and Irish barristers and Scottish advocates could be admitted to practice in New South Wales. However, by the Barristers Admission Act 1848, the Barristers Admission Board was established, consisting of all of the judges of the Supreme Court plus two practising barristers. The function of the Board was to oversee the admission of persons with appropriate local qualifications as barristers by the Supreme Court of New South Wales. Candidates who were not Barristers of England or Ireland or Advocates of Scotland were to be examined by the Board, not only in Law, but also in Greek and Latin, Mathematics, and any other branch of knowledge deemed appropriate by the Board.

After February 1888, solicitors of five years’ standing, on first having their names struck off the Roll of Solicitors, could be admitted to the Bar. I expect that many of you, as I was, were first admitted as an attorney, solicitor and proctor of the Supreme Court before being subsequently admitted to the Bar of NSW. The period between having your name removed from the Roll and being admitted to the Bar was somewhat nerve-wracking. The 1898 Act was replaced by the Legal Profession Act 1987, which abolished separate admission as a barrister or as a solicitor and substituted admission as a legal practitioner. Under the Legal Profession Uniform Law (NSW) 2014 you would now be admitted to the Australian legal profession as an Australian lawyer.

After you were called to the Bar, you came in contact with another connection with Roman antiquity. That is to say, you began reading with a junior barrister, who was your tutor, and you were his or her pupil, or pupillus. That terminology harks back to the institution of tutela, or tutorship, in Roman Law. The Latin word pupillus meant, literally, an orphan. The Latin word tutor meant, literally, a defender or protector, and came to have a technical meaning in relation to the estate of a child who was an orphan. Of course, the words mean something different in today’s English. However, there are some analogies. Thus, in Roman law, an infant subject to tutorship could not enter into any transaction without the auctoritas, or approval, of his or her tutor.

Similarly, a pupil at the Bar was not permitted to accept a brief without the approval of his or her tutor and a barrister’s obligation, as tutor, was to provide guidance and advice to the pupil. Of course, today, the terminology is now ‘Master’ and ‘Reader’, losing the somewhat romantic connection with Roman antiquity.

Instruction and examination of readers by the Bar Association was somewhat looser when you came to the Bar than it is these days. As you will recall, in the early 1980s, the Bar’s Reading and Education Committee provided a ‘course of practical instruction’ consisting of 12 lectures delivered on Monday afternoons, which covered such topics as the history and traditions of the bar in England and New South Wales, professional conduct and etiquette, the privileges and responsibilities of an advocate, the technique of using a law library and legal research and the practice and law relating to matters in the Court of Petty Sessions. Your tutor was also expected to instruct you in the rules of etiquette. For example, when robed on the way to court, senior counsel was not to carry anything other than an umbrella or a cigar, the latter being a concession to Roddy Meagher. Juniors, on the other hand, were not to be seen robed in public unless carrying something. That rule was abandoned when Michael McHugh, as president of the Bar Association, was observed striding to court empty-handed followed by his junior, Annabelle Bennett, some 18 inches shorter and much slighter than Michael, struggling under piles of folders. That was before the days of the trolley. You will recall the disdain with which Victorian silks were regarded by their Sydney brethren when observed setting off to court trundling an undignified wheelie bag behind them containing their briefs. Only silks could put their red bags on the bar table and no blue bag was ever to be seen on a Bar table. In the Supreme Court and the District Court, whose judges were invariably appointed from the Bar, the convention was that you did not need to give your name when announcing your appearance, since all of the judges were presumed to know all members of the bar from which they had appointed. In the early days, that was probably the case. However, it was not necessarily so by the early 1970s and, to avoid embarrassing a judge who should remember your name but forgot, it was doubly important to fill in an appearance slip.

The Bar Association published approved routes for walking from chambers to court while robed, to ensure that there was no undue advertising by members of the Bar. You will all recall the very senior junior barrister who was castigated by the Bar Council for eating a meat pie in Macquarie Street while fully robed. Such conduct was regarded as quite inconsistent with the dignity of the NSW Bar.

You will also remember the memo from Captain Cook, the Registrar of the Bar, after a Supreme Court judge was scandalised by the attire of a barrister who appeared before him in chambers in a safari suit with short sleeves, no less. The Bar Association agreed that that mode of dress was inappropriate, and members were urged to wear dark clothes when robed and to wear suit and tie when appearing on chamber applications. Women barristers were asked to avoid wearing clothes of a colour or type that would clash with robes and, when appearing on chamber applications, to dress as for ‘business occasions’.

When you joined the Bar, the two-counsel rule still applied, and senior counsel could not be briefed without a junior. That was an advantage for new members of the Bar who had a greater opportunity of a junior brief. Perhaps more advantageous for new barristers was the rule that the junior was entitled to charge two thirds of the fee charged by his or her leader. There are various views as to whether the rules were against the public interest.

Another rule that was in force when you were first called to the Bar was the requirement that, apart from dock briefs, a barrister could only be briefed by a solicitor and not directly by a client. On the other hand, the solicitor had no legally enforceable liability for the barrister’s fees. Fees were a matter of honour only. The sanction developed by the Bar was the Black List, a list circulated of solicitors who had defaulted in the payment of fees and whose default had been reported to the Bar Association by a barrister. It was a breach of etiquette for a barrister to accept a brief from a solicitor on the Black List unless payment of the fees was made with the delivery of the brief.

Ancient Rome is said to be the origin of the rule that barristers’ fees were a debt of honour and not a legally recoverable debt. The Romans distinguished between jurists and advocates, jurisprudentes and advocati. The jurists rather looked down upon the advocates. Most people have heard of Cicero, the famous Roman advocate. A jurist friend of Cicero’s, Aquilius Gallus, used to say, when anyone presented him with a problem that involved a question of fact ‘This is not law, this is a job for Cicero’. Cicero, on the other hand, asserted that knowledge of the law was neither more nor less necessary for a great advocate than other sorts of general knowledge, such as history, geography or philosophy. The advocate consulted the jurist when he needed detailed legal advice. Jurists and advocates were members of the Roman upper class, for whom public and political office was merely an incident of a life of leisure. A jurist or advocate who gave an opinion or appeared in court was expected to do so voluntarily without charge. To contract for the payment of a fee would have been regarded as infra dignitatem. Nevertheless, there developed an expectation on the part of advocates that, although they were not entitled to be paid any remuneration, they expected an honorarium, namely, a gift from a grateful client.

The relationship into which advocates entered was regarded as one between patronus or patron, on the one hand, and cliens, or client, on the other hand, usually between a person of higher social rank and a person of lower social rank. The patron was the protector, sponsor, and benefactor of the client. However, after the devastation of the Second Punic War with Carthage, it appears that patrons were motivated to extract considerable gifts from clients and, in 204 BC, the tribune, Marcus Cincius Alimentus, proposed the enactment of a statute that contained an absolute prohibition on gifts to advocates for the pleading of cases.

In ancient Rome, a statute was named after the magistrate who proposed it and the statute is therefore known as the Lex Cincia. The Lex Cincia probably served an expressive function more than anything else, since it made no provision for voiding gifts or imposing sanctions for breach. According to one of the great Roman classical jurists of the early 3rd Century, Domitius Ulpianus, or Ulpian, the Lex Cincia was a lex imperfecta, as distinct from a lex perfecta and a lex minus quam perfecta. A lex perfecta prohibited particular conduct and if contravening conduct took place invalidated the contravening conduct and imposed a penalty for the contravention. A lex minus quam perfecta prohibited particular conduct and imposed a penalty for its contravention but did not invalidate the prohibited conduct. A lex imperfecta prohibited conduct but neither invalidated the contravening conduct nor imposed a penalty for contravention.

In his introductory essay for the Bar Association Centenary Essays, Murray Gleeson said that among the greatest insults a barrister can be offered is to be described as a mouthpiece for a client, who will obey any instructions from the client, put up any argument, fight any case, and do whatever is necessary to win.

Might I finish by recounting one of my favourite stories from Roman jurisprudence, showing the analogy between ancient Rome and modern NSW. The story involves the great Roman jurist, Aemilius Papinianus, or Papinian, who was regarded as the greatest of the ancient jurists. Papinian was chief legal advisor to the Roman emperor, Septimius Severus. That is to say, he was the ancient equivalent of the Solicitor-General. In AD 211, Septimius died and was succeeded by his two sons, Caracalla and Geta, as joint rulers.

However, Caracalla resented sharing power with his brother and murdered Geta in the arms of their mother. Under Roman law, that constituted the heinous crime of parricide, which carried the bizarre punishment of being tied up in a sack with a monkey, a cock, a dog and a snake and being hurled into the nearest ocean or deep river. Since Caracalla was not anxious to suffer such a fate, he called on Papinian, as his chief legal advisor, to compose a legal justification for the killing of Geta. The noble reply of Papinian was that it is easier to commit parricide than to justify it. He refused to compromise his principles and undermine the rule of law by composing a false justification for an unlawful act. For that, Caracalla had Papinian put to death. While a barrister should not necessarily sacrifice her or his life in the service of the law, I am confident that, in the 50 years since your admission to the Bar of NSW, you have all abided by the sentiment expressed by Murray Gleeson, and that you have only given the advice that you believe to be correct, and not simply advice that you think your clients wanted to hear. May I congratulate each of you on your marvellous achievement. BN