- Winter 2022

- Electoral Law outlawing the duplication of words between political party names found constitutional

Electoral Law outlawing the duplication of words between political party names found constitutional

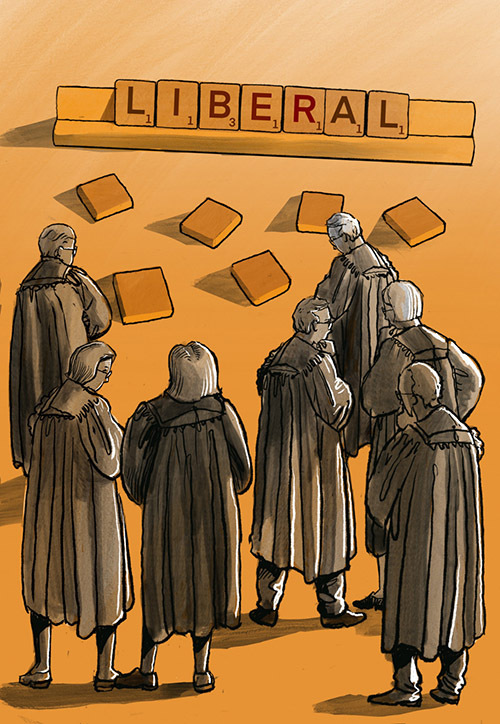

By a slim majority that saw its three most senior judges in dissent, the High Court has confirmed the constitutionality of amendments to the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) (Electoral Act) which require deregistration of a political party whose name shares a word with a party that was registered before it.

Background

This proceeding, which was a special case in the original jurisdiction of the High Court, concerned the constitutionality of a set of 2021 amendments to the Electoral Act. The provisions prevented the registration of a political party whose name shared a common word with the name of another party that had already registered with the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), without that original party’s consent. The amendments also provided for the deregistration of a political party whose name had a word in common with another party, on the objection of the earlier registered party. The purpose of the amendments was said to be to avoid voter confusion at the ballot box.

John Ruddick, the lead Senate candidate for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in NSW at the 2022 election, brought the special case, arguing that the provisions were contrary to the requirements in ss 7 and 24 of the Constitution that candidates for election be ‘directly chosen by the people’ and that they also contravened the implied freedom of political communication.

Since its name included the word ‘Liberal’ and the party was registered in 2008, later than the Liberal Party of Australia, the LDP faced deregistration under the impugned provisions. The name of the LDP was part of the impetus for the amendments’ introduction. At the 2013 federal election, to its own surprise, the LDP received 9.5 per cent of votes in the Senate election for NSW, leading to the election of the party’s first senator, David Leyonhjelm. The random ballot draw had resulted in the LDP being listed in the first column of the large Senate ballot paper, while the Liberal and National parties, grouped together, were placed in the 25th column. Soon after the election, Senator-elect Leyonhjelm speculated in a radio interview that up to 75 per cent of people who voted for his party in NSW may have confused it with other parties, including the Liberal Party. The plaintiff’s pleading conceded that some voters in the 2013 election unintentionally voted for the LDP because they were confused as to the party affiliation of LDP candidates.

The majority

In a joint judgment, Gordon, Edelman and Gleeson JJ found that both limbs of the plaintiff’s argument failed at the threshold. There was no factual material in the special case demonstrating that the amendments burdened the quality of electoral choice by the people or the freedom of political communication (at [111]). Instead, the amendments would likely improve the clarity and quality of electoral choice and political communication (at [162]). There was no factual basis to conclude that any advantage would accrue to a prior registered party, other than winning votes of people who would otherwise have been confused (at [159]). If it were deregistered, the LDP could still conduct political advertising and communicate its political philosophy under that name (at [166]).

Their Honours also noted that while the name ‘Liberal Democratic Party’ could not be printed alongside its candidates’ names on a ballot paper, which may be considered a small constraint upon political communication and the quality of electoral choice, parties in the LDP’s position could hand out ‘how to vote’ cards explaining that they would have an alternative name on the ballot paper, including any derivative word from ‘Liberal’ (at [170]). The net effect would be the enhancement of the interests protected by ss 7 and 24 of the Constitution and, in particular, confusion would be reduced (at [166]).

In a brief judgment, Steward J concurred with those reasons. He found that the ‘heavy-handed’ provisions, conferring enduring monopolies over the words ‘liberal’ and ‘labor’ to the major parties, may be unappealing but that the court should only intervene in the case of more extreme laws which offend the ‘most essential of democratic values and systems’ (at [174]).

The minority

Writing together, Kiefel CJ and Keane J found the amendments prevented voters from being presented with the party affiliation of candidates on ballot papers (at [3]). There was no substantial reason or justification for the considerable burden on the informed choice of electors and on political communication. In particular, other provisions of the Electoral Act already allowed the AEC to deregister a party whose name resembled another’s or suggested a connection that did not exist (at [3]). In their Honours’ view, the special case showed that the position of a party on a ballot might affect votes, but the facts did not prove the confusion arose from the use of a word like ‘liberal’ alone ([15]).

Justice Gageler would also have found the provisions unconstitutional. He reasoned that they created a legal impediment to the receipt of information – a candidate’s party affiliation – which bears on the making of an informed choice (at [31]). The amendments did not satisfy the two conditions of their constitutionality – that their purpose, and that the manner the purpose was pursued, be compatible with constitutionally prescribed system of government ([28]- [30]). As the amendments discriminated in favour of incumbency (and would not lead to the deregistration of any political parties represented in the House of Representatives or Senate after the 2019 election), a strict necessity standard should be applied (at [83]). The amendments had no compelling justification. In particular, the material failed to demonstrate that there was a meaningful risk of voter confusion based solely on the fact that a political party’s name contained a word in the name of another party (at [104]). BN