- Winter 2024

- Editor's Note

This issue of Bar News is dedicated to the celebration of the bicentenary of the Supreme Court of New South Wales. The various ceremonies and works that formed the Bicentennial Project were appropriately steeped in history, and we cover each in this issue.

What resonates when one considers the history of the Court are the stories that are embedded in it. Some stories are foundational, an interweaving of constitutional and political problems that found their solutions in the establishment of the Court and its work. We cover some of those stories in this issue (see p 44 and p 46).

A detailed treatment of the history of the Court is recorded in Mason and Reid’s Constant Guardian, Changing Times: The Supreme Court of New South Wales 1824–2024, the launch of which is covered here together with an interview with the editors (p 28 and p 30). The book is a painstaking examination of the important features of the Court but what marks it as a brilliant and engaging read is the stories it collects together.

The Supreme Court is the sum of many parts – at once an institution; an organ of government; a collection of buildings; a function of its legislation, rules, procedures and conventions; a venue for the settlement of certain disputes. Functionally, it is the sum of the people who make it up, be they judges, officers and staff, lawyers, litigants and observers.1

Many of the stories captured in Constant Guardian, Changing Times concern the people who come before the Court. Their stories are told in the evidence led in Court and recorded in its judgments. Many of the stories are mundane, but not to the parties. Some are celebrated or salacious, in modern times the subject of nationwide coverage and (judge permitting) hundreds, or even thousands, of views on a live stream.

The book records the stories behind many important cases, including major criminal trials2 and the often tragic, occasionally triumphant, cases concerning the Indigenous people of New South Wales and beyond. The Chief Justice’s speech at the bicentenary celebrations (p 24) contains acknowledgement of the generous contributions of the Waridjuri, Kalkadunga and Wirdi men who participated in the ceremonial sitting.

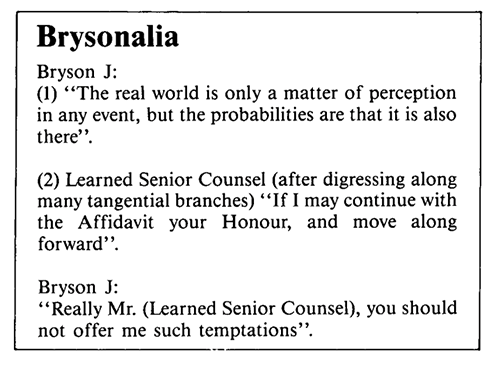

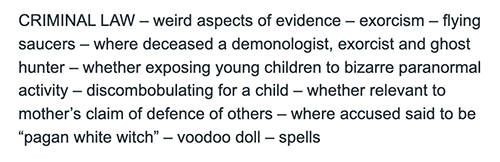

Presiding over the people are the judges of the Court. Constant Guardian, Changing Times contains a chapter that captures the judges ‘as people’. It opens with a vignette about Justice John Bryson, including that he was a regular contributor to Bar News and that his wittier lines from judgments and argument were recorded as ‘Brysonalia’ – an example of which is set out here. A current version might be entitled ‘Catchword corner’ and feature the fine work of Justice Hamill (sample provided).3

This edition contains a number of features on judicial appointments and retirements, including an interview with Justice Mortimer of the Federal Court (p 68) and pieces on a number of new and retiring judges, each written by someone who knows them well. This approach achieves varying levels of formality but I hope captures the judges ‘as people’ beyond their impressive professional histories.4

Constant Guardian, Changing Times also contains a chapter on the officers and staff of the Court. It is an excellent historical and personal account of the people who keep the Court running. Any barrister worthy of the name maintains an interest in the Court’s staff, from the particular case management philosophy of each of the registrars to the formidable and efficient judges’ associates whom one would do well to remember by name and treat with due deference. Those who understand and respect the work done by the Court staff will always have an easier time in the Court than those who don’t.

For this issue Penny Thew spoke to some of the registrars and prothonotary of the Court about their work, many of whom our members will know from their earliest appearances on coming to the Bar (p 40). It is a disappointment that, due to timing, we missed the opportunity to speak with some of the longest standing but recently retired registrars, including the brilliant Principal Registrar Chris D’Aeth; the endlessly patient and steadfast Court of Appeal Registrar Jerry Riznyczok, who shepherded countless litigants in person through the necessary procedural steps to have their appeals ready for the court; and Common Law Registrar Chris Bradford, an oasis of calm in a very busy list.

Constant Guardian, Changing Times dedicates one chapter to lawyers and litigants, though they are featured throughout the book. Reflecting on the relationship between the profession and the Court, there is more than it being the point of entry for newly admitted lawyers or the ultimate source of professional discipline. For those who practice regularly in the Supreme or any other court, there is a sense of familiarity and belonging within it – a sense of home.

That slightly pathological sentiment can be justified by the choice we in the profession have made to participate in the administration of justice by arguing cases in court. It is explicable by the time we spend in the Court, year on year, familiarising ourselves with the workings of the place and its people. It is exemplified when we use that familiarity to assist new lawyers, litigants and witnesses to negotiate their way through the formalities and procedures of the Court.

I first became conscious of the Court as a place of belonging after COVID when in-person hearings recommenced. The relief of not having to argue trials and appeals before the frozen face of one of the judges (or a tipstaff if the AV link failed early enough) was great, but what struck me was the feeling of happiness of being back in the Court building: greeting the court officers and associates, searching in vain for the water, trying not to get the gown caught in the chair, saying to your opponent “it’s just nice to be back in here”.

Constant Guardian, Changing Times devotes some pages to the buildings of the Court and their contents, including their art. Each of the Sydney buildings that house the Court have their own sense of grandeur (depending on your attitude to brutalism) and of grudging familiarity to their occupants, be it peril of great flood in the Queens Square building, or the vagaries of running a major criminal trial in the ancient setup of the St James Road Court, or the dilemma of slow lift vs endless stairs in the Hospital Road Court. Part of the Bicentennial Project has been the development of the History Wall and the gallery walls on level 13 of the Queens Square Court, which collect together within the building itself some of its history and its people. We spoke to the curator, Sophie Howard, about the process she undertook in putting together the collection (p 34).

A tremendous amount of work went into the Bicentennial Project, and the result is a record of one of the great institutions of the state and the people and stories that make it so. This issue attempts to record the event and the elements that make it up as an accompaniment to the celebrations, and as a tribute to the people who worked so hard to memorialise the Court.

ENDNOTES

1 Page 380 of Constant Guardian, Changing Times contains a fitting tribute to two dedicated ‘court watchers’ and friends, Robin Gandevia and Denis Sullivan, who were as much a part of the Court as anyone who worked there.

2 For further reading, see former Bar News editor Jeremy Stoljar SC’s 2011 book The Australian Book of Great Trials: The cases that shaped a nation.

3 It should be noted that this idea came independently of the editors of Constant Guardian, Changing Times, see p 384.

4 The first recorded judge in the Table of Judges of the Supreme Court in Constant Guardian, Changing Times is Sir Francis Forbes. The last recorded judge as at the date of publication is James Hmelnitsky, who I’m pleased to say is profiled in this issue, as is the judge before him in the list, Ian Pike.