- Summer 2023

- Bully for Bullfry

‘There is `bullying’ and then there is bullying,’ mused Jack Bullfry, as he looked at the day’s transcript, and sipped his Negroni. He had not raised his voice but had he, perhaps, displayed too much invective in his cross-examination? Things were certainly more robust years ago when he had started but the profession had changed for the better – litigation was not the blood sport it had been; the dishonourable art of ‘sledging’ had all but disappeared.

Thankfully, long gone are the days of the Irish Bar when Serjeant Armstrong used his most potent weapon, ‘ridicule.’ ‘His great weapon was ridicule. He laughed at the witness and made everyone else laugh. The witness got confused and lost his temper, and then Armstrong pounded him like a champion in the ring.’1

What to do when attacked by a judicial ‘bully’? First, remember when confronted by a fractious tribunal to keep Proverbs 15 front and centre: ‘A soft answer turneth away wrath: but grievous words stir up anger. The tongue of the wise useth knowledge aright: but the mouth of fools poureth out foolishness.’

That, of course, is a talent in the repertoire of every good advocate – that ability to disarm a judicial onslaught with guile, or charm, and make the worse appear the better case. And such onslaughts may, by definition, occur in even the best conducted matters.

In such a storm it is the bounden duty of counsel (although there was no Bar Rule about it) to confront the problem as best one can. Most importantly, on no account and on no occasion should the advocate point to those instructing him as the source of all the difficulty! And yet Bullfry had seen that sad, deflecting ‘excuse’ raised by weaker counsel on many occasions.

The only reason counsel is deployed in a matter is because the instructing solicitor puts his or her faith in counsel to do two things: first, make sure by advice and otherwise that the matter is ready for judicial determination, and secondly, stand up in court and take the forensic fire as it descends. Every solicitor is entitled to appear in any court in the Commonwealth – it is only a certain inner fecklessness (best left unexamined in almost every case) in the cadet branch of the profession which provides the separate Bar with its daily bread, and any work at all. If every solicitor was prepared to stand fire for putting difficult propositions to the court the Bar would cease to exist.

Bullfry recalled a fraught matter in which, before he was deployed, various judgment debtors had failed to abide by the relevant orders of the Court requiring them to account to certain ex-partners and obey certain directions. They had been misinformed that there was no need to do so on the most tendentious of technical bases. The matter came back for the fifth time on a contempt application and Bullfry said simply to the forbidding Equity Division judge: ‘Your Honour, I have explained the position to my clients and they now offer a full and open apology to the Court for their previous behaviour.’ The judge said, ‘That is the first time in five hearings, Mr Bullfry, that a proper explanation and apology for otherwise contumelious behaviour has been given to the Court’.

There are, of course, many legendary sharp exchanges between Bench and Bar. SEK Hulme fleshes out the famous retort of Hayden Starke to the High Court as told to him by Sir Garfield Barwick.2

No one announced an appearance for the respondent. The dreadful silence was broken by a very nervous solicitor telling the court that Mr Hayden Starke had been briefed, but he did not appear to be present. The court adjourned while Mr Starke was sent for. Mr Starke came up from Selborne Chambers, the case was called again, Mr Starke announced his appearance for the appellant, and sat down.

The Chief Justice, the vastly august Sir Samuel Griffith, intervened.

‘Mr Starke, the court is waiting.’

Mr Starke got to his feet, announced his appearance in a considerably louder voice, and sat down.

‘You do not take my point, Mr Starke. The court has been kept waiting, and the court expects an apology.’

That was not what the court got.

What it got was ‘This court is paid to wait. I am not.’

What intrigued Barwick was what in the ultimate the court could do. Was it contempt of court, to keep the High Court waiting? If not, was it contempt not to apologise for having done so? Was it all merely rude?

The questions remain open. He had always advised young barristers that those who lack the formidable forensic power, which Dixon saw in Starke, would do well not to learn the answers. They will do well to stay on hand. If something does go wrong, they will find it more comfortable, and possibly safer, to apologise.

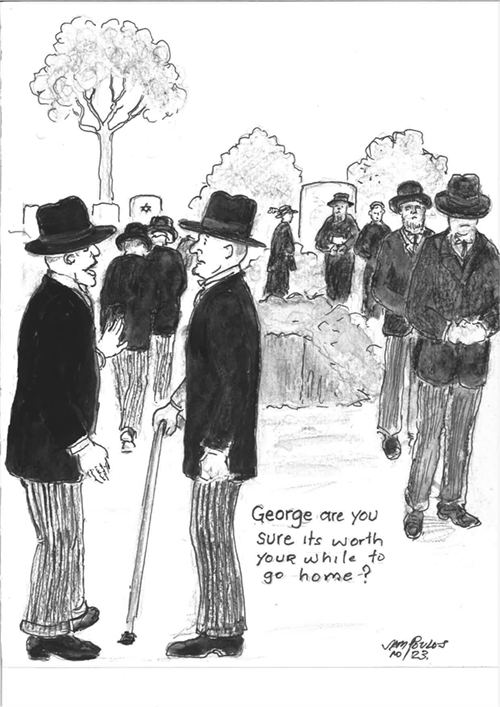

(This anecdote was all of a piece with Starke’s ‘pitiless’ demeanour (Dixon CJ’s epithet). At the funeral of Sir Isaac Isaacs, Sir Garfield Barwick recalled an open grave ceremony held on one of the hottest days that Melbourne could record. As his erstwhile brothers filed past the open grave, Starke leant forward to his colleague and octogenarian, Sir George Rich, and asked ‘George, are you sure it’s worth your while to go home?’)

Secondly, don’t run before you can walk – if you have a criminal practice, start after a stint at Legal Aid or the Crown Prosecutor gaining experience in smaller matters in the criminal calendar – don’t let your first matter involve your client’s wife’s head in a refrigerator.

A distinguished commentator3 has said that:

‘… employers of legal practitioners have a responsibility to make sure that young lawyers are ready to go to court. That obligation requires that new lawyers are given sufficient training and support to appear in court with confidence and with mechanisms to overcome their natural anxiety. They should only be given court appearances commensurate with their experience and skill’.

You must learn from your earliest days to resist any overbearing from the Court – but without ‘crossing the line’. Fully forty five years ago, Bullfry had been a callow prosecutor. The chief magistrate, impatient to move matters forward, had told the police witness under examination-in-chief to hand over his notebook to speed up judicial note-taking. Foolishly, Bullfry acceded to the request. Almost immediately disaster struck when inadmissible material in the notebook came to light.

‘Mr Bullfry, I shall have to recuse myself now. This entire waste of time is down to your ineptitude.’

Bullfry returned, chastened to the office, where the Colonel simply grunted and said: ‘A lesson to be learnt, lad, a lesson to be learnt.’ Some weeks later the scene began to repeat itself. But this time Bullfry said simply, ‘Your Worship, we both came unstuck following that course recently, and it is not happening again!’

Good humour always has a part to play. Audley Gillespie-Jones4 recalled an incident before Sir John Barry who was out of temper with the conduct of the proceeding before him. Towards the end of the second day Trevor Rapke made a funny remark.

‘Everyone laughed except the judge who said: `I am sick and tired of those stupid remarks from the Bar table and the next person who makes one I shall fine for contempt of court and the fine shall be ten guineas.’

All the other counsel looked like zombies but Gill said, ‘I am not going to let him get away with that’ and stood up. Rapke said, ‘Don’t be a bloody fool’ and kept a tight grip on Gill’s gown.

Sir John Barry said, ‘What do you want?’

‘If I am unlucky enough to incur your Honour’s displeasure, may I have time to pay?’

Sir John brought up his clenched fist, then half-smiled and said:

‘That was funny. You were lucky.’

‘If I have done anything to dispel the horrible gloom caused by your Honour, it has served its purpose, and will you now ask Mr Rapke to let go of my gown!’

Counsel may, of course, be guilty of bullying behaviour – and this should not occur. It is never appropriate to lose one’s temper with the court, or to invite a judge to ‘do as you please,’ rather than to persuade the judge as the client’s interest properly demands and supports. As Kirby P noted5 in Escobar v Spindaleri:

‘Courage and resolution on the part of counsel does not stop at an assertion of the right to conduct the case as counsel thinks best. Courage is not exhibited by inviting a trial judge to do as he pleases. It is the duty of counsel to represent his client. In that representation, it is his obligation to ensure his client’s case is presented and argued to the best of his skill and ability. In these circumstances it is not the counsel who invites the judge to do as he pleases. It is a duty of counsel to endeavour to persuade the judge to do as his client’s interests necessitate, to the extent to which those interests might lawfully be pressed.

‘As has been said, in the atmosphere of the courtroom, emotions sometimes run high. But when they are indulged at the expense of the protection of the client’s interest, they ill-become counsel whose duty is to represent those interests.’ (Emphasis supplied.)

All this is, perhaps, a counsel of perfection. Some judges are naturally atrabilious, lack a judicial temperament, and have been worn down by the daily grind of obtuse, and unhelpful, submissions. Judging is a lonely post; it is easy to become ‘hoity toity’ when one’s behaviour is on daily public display – but ‘God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb.’ BN

ENDNOTES

1 FL Wellman The Art of Cross-examination (1931 Macmillan) page 54 quoted by Ryan SC in ‘Propriety and impropriety in cross-examination’ Bar Association CPD Seminar 17 June 2008 at [31]. The entire paper repays the closest reading.

2 Victorian Bar News Autumn 2003 SEK Hulme, ‘Characters of Bench and Bar’ (a speech delivered 4 June 2002) pages 28 – 29.

3 Mr J Phillips SC, ‘Judicial Bullying’ delivered 4 August 2017 ((2018) 8 WWR 138).

4 AS Gillespie-Jones, The lawyer who laughed (1978) pages 25 – 26. Audley Sinclair Gillespie-Jones (1914 – 2000) was a celebrated VFL footballer (Melbourne and Fitzroy) and practised latterly in the ACT. For his obituary, see Victorian Bar News Spring 2000, page 20. Bullfry appeared against him many times in the late seventies; by that stage he was almost blind but indomitable.

5 (1986) 7 NSWLR 51 at 54 – 55.