- Winter 2024

- Bullfry and the Zeitgeist

O tempora, o mores? Or was tempora mutantur et nos mutamur in illis more seasonable to the modern ear?

The first quotation is the lamentation of a petulant old man whom Time has surprised; the second, a timely adjuration to keep up-to-date, to master the complexities of Dropbox, to read with attention the latest exquisite offering of the Corporations List Judge on the meaning of a ‘redeemable preference share’, to get used to cross-examining via AVL, to walk at least once around Hyde Park after a salad lunch, to stop at one negroni before dinner – the list of resolutions to keep abreast of the times is never-ending.

Yes, Postumus, the years are flying by. But hadn’t Australia’s greatest jurist summed up the correct approach to change: ‘I am not one of those who subscribe to the view that the older you get the better you get … I believe in young everything’?

Bullfry had enjoyed both the speeches at the recent evening ‘memorial’ for the begetter of the Commercial List, sadly and suddenly departed, and the Supreme Court’s proverbially generous hospitality at its end – he had tucked into the sandwiches and canapes, chased by an ample red, with his usual gusto. (He had chanced to chat to the deceased honorand less than a month before his demise at their local hostelry – the latter had been withdrawing a wad of ‘avocadoes’ from the gaming room’s ATM – ‘That’s a lot of money for a senior citizen to be carrying, Andrew,’ Bullfry had admonished. ‘A man never knows when he might need cash,’ his addressee had responded, in his inimitable, Central European accent, with his usual smile and twinkle in his eye!)

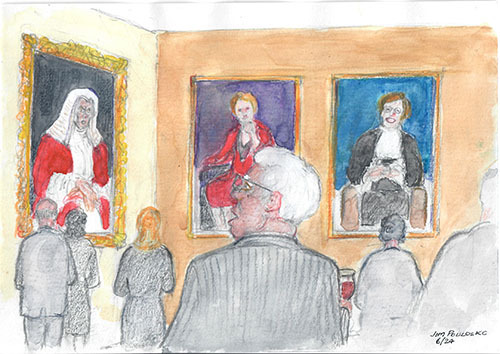

On the evening of that commemoration, he had roamed the vestibule of the Banco Court, wine in hand, absorbing the detailed historical display and the Zeitgeist as it had changed over two centuries since the court’s foundation.

The earlier portraiture displayed a uniform mundanity – oil painting after oil painting, all of mice peeping out of oakum. Then, thankfully, a change to a more relaxed sartorial style and a less stereotypical portraiture, rounded out by renderings of retired senior female jurists at the corridor’s end.

And then, a week or two later, a celebration of the court’s bicentenary. Perched high up (close to the soloist), Bullfry had enjoyed a panoptic view of proceedings. All was conducted superbly.

As he listened to the mournful drone of the didgeridoo and the following ‘song’, entirely appropriate as a prodrome to the sombre institutional memories sometimes evoked by speakers, two conflicting quotations flashed into Bullfry’s mind that captured the essence of the proceedings.

‘The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there’ and ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’ Hartley and Faulkner – could both statements be true? Indeed, they could.

Looking back showed both how much things had changed, and how much abided. An early complaint (circa 1828) mentioned by one speaker, that the new court infrastructure lacked a ‘dungeon’ for the remand prisoners, had brought a laugh from the audience. Yet, the current judges were still clothed (and bewigged) in 18th-century garb – the orotund Proclamation, magnificently delivered, as always, by the dignified Canadian usher had signalled the commencement of proceedings but had not changed in two centuries. (Although for Bullfry a Law French welcome – ‘Oyez, oyez etc’ – would still have resonated).

But an important point, highlighted by the speakers and differing completely from the Mother Country, demonstrated the vigour of the new Colony and its determination to break from the structures and strictures of the past. From the very beginning, over protestations from the would-be monopolists who would have profited most from its imposition, the court had not restricted the right of advocacy to a limited class of counsel, instead permitting every practitioner admitted to it to address it and conduct litigation before it. So it was that we have avoided the ‘distinctions’ which still bedevil practice in England (and Hong Kong) where those called to the Bar alone may exercise a right of audience. This was all in keeping with the egalitarianism of the Colony, and no doubt because of a need to accommodate ‘ticket-of-leave’ men and the like.

And in the court’s procedures, much remained that would not have surprised a practitioner from the time of its creation. Certainly, there were no trumpeters or javelin men to welcome an Assize in Albury. But the court still ‘toured’ to make sure that the large conurbations enjoyed its presence. A barrister opening a case to a jury would still follow the same processes.

And in keeping with modern times, the court now facilitated many methods of dispute resolution. Whether this could be done and still retain the dignity (majesty?) of the judicial process was a difficult question to answer. The press of modern business in a contemporary courtroom before a judge (let alone the telephone queue in truncated hearings before a registrar) meant that many old solemnities had to go. The steady advance of ADR in all its manifestations was an indirect threat to the continued existence of an independent Bar, and advocacy generally, notwithstanding its undoubted economic efficiency.

And not all innovation is beneficent, efficient though it may be. Bullfry had noted with some concern the introduction of a new ‘filtering’ system for appeals to our federal Supreme Tribunal. In the United States, counsel may address the Supreme Court for half an hour! In the United Kingdom, at most a day for each side. In Australia, in the 1930s, distinguished counsel might say to the High Court when questioned on timing: ‘I intend to address that point next Thursday’. Those days were long gone – quick, efficient, and just – with Aon omnipresent.

We have not reached the stage of circumscribed time limits – yet. But the introduction of something along the lines of a ‘cert. pool’ into the process of appeal threatens the same future. In the United States, ‘law clerks’ (sic) do most of the preliminary ‘winnowing’ of applications for certiorari to permit a full hearing by the Supreme Court. Such applications are decided ‘on the papers’ without the benefit of oral argument and (without reasons) their curt refusal – ‘Cert. denied’).

The severe restriction on oral Special Leave applications under a new dispensation is a step away from the orality that has always been the hallmark of our entire appellate system. Sure, it is that the court as a whole will examine the merits of a potential appeal by means of an internal, judicially prepared Memorandum. There will be no direct delegation to assistants, however well qualified. But that seems to be an administratively burdensome exercise.

As well, a viva voce examination of the merits of an application for Special Leave performs a number of important functions: it helps narrow the precise area of dispute; it illuminates at an early stage the way in which a court might approach the problem; it assists counsel in determining how the matter might be better conducted. And it can provide a portent of legal development – who will forget the celebrated case, now decades old, in which a distinguished silk had been found liable for negligence at first instance in failing to advise in conference that the grant of Special Leave some days before might presage an important change in company law?

Bullfry recalled appearing with another well-distinguished silk, many years before, to seek leave in a complicated federal case – the application was listed for hearing immediately after lunch, and in the morning hearings, only two judges had been disposing of business.

As the matter was called, his leader leant across and grabbed Bullfry by the arm with the whispered, urgent observation, ‘Three are coming on!’ Bullfry was nonplussed – but, of course, his leader realised instantly that we were in with a fighting chance, since a tie-breaker might be required to determine the delicate question.

If an associate with a PhD and parachute training is now to be deployed to prepare a Memorandum on the ‘merits’ of a prospective appeal, these then to be briefly examined in conclave by those exercising judicial power, an important and indefinable element will be lost to the system. As Owen Dixon noted long ago, the most important person for whom a judge is writing is the party who is going to lose. Merely receiving a curt, written, ‘template’ refusal should not suffice.

Orta recens quam pura nites? The past is never past. Was it time to consider more fundamental changes to those vestiges of the first foundation and all it had brought with it, for good and ill? The motto’s cheery Latinity concealed a large number of very dark, unpleasant events, but these had been fully acknowledged at the court’s bicentenary – and the Zeitgeist seemed ever so slowly to be accommodating them.