- Winter 2023

- Bullfry and the Swan Hill Swagman

Bullfry, Negroni in hand, reread the offending passage in Citta v Hobart City Council1 with renewed concern. Ever since he had enjoyed a practice for the federal Department of Health (‘passive smoking’; ‘robot pills’ and the like) the complexities in the attempted exercise of federal jurisdiction had entranced him.

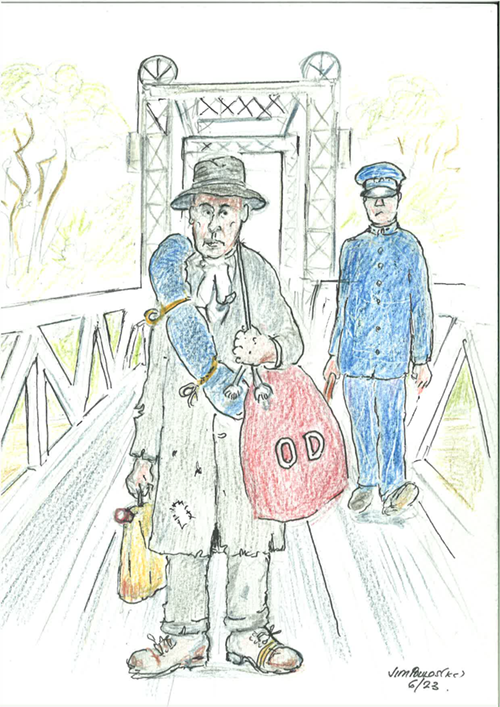

It was unheard of for the High Court to ‘diss’ even an extra-curial statement of Sir Owen Dixon – but there it was, Homer had nodded, and Sir Owen himself had uttered words now stigmatised by the High Court as ‘constitutional nonsense’! Dixon KC’s suggestion that a tramp (‘swagman’) crossing the bridge at Swan Hill and arrested for vagrancy might invoke section 922 of the Constitution and immediately attract federal jurisdiction was completely wrong.

‘…(T)he federal jurisdiction of this court under s 76(i) or s 76 (ii) or of another court under s 77(i) or s 77(iii) of the Constitution is not engaged, by the assertion of a claim or defence that amounts to ‘constitutional nonsense’ or any other form of legal nonsense. But examination of what the prospects of success of a legally coherent claim or defence might be, were that claim or defence to be judicially determined on its merits, forms no part of the requisite assessment.’3

That ‘test’ struck Bullfry as a little strained, particularly since there was strong authority to the effect that whether any federal claim at all arose might be discerned from preliminary correspondence inter partes.

And an abiding, fundamental, problem as noted without irony by the Full Federal Court in Tucker v McKee4 was that ‘The question of the breadth of the controversy is not straightforward’. So it was that a ‘matter’ with disparate parts, some depending on contract, some on Equity, and some on the federal Noxious Weeds legislation might all be gathered together into one ‘matter’ and heard in the Federal Court. And once attracted, that jurisdiction would not be lost, even if the obviously ‘federal’ part of it was dismissed brevi manu.

Indeed, to take an extreme example, by various jurisdictional twisting and turning, even a claim for defamation might come before a judge of the Federal Court of Australia sitting without a jury. And that might occur if there was a mere ‘assertion’ in a submission that the alleged defamation might have been read in the Australian Capital Territory!5

At least the ‘ambit’ argument, so it appeared, that any case at all which involved a corporation fell within the jurisdiction of the Federal Court had received its quietus6 – had it not, the Supreme Courts of the States could have been entirely denuded of commercial jurisdiction.

But why is there a Federal Court at all? – although it was far too late now to do anything about it. This question had long perplexed Bullfry. Prior to its establishment almost fifty years ago, the Supreme Courts of the States had successfully exercised a plenitude of federal jurisdiction (save only in bankruptcy which was, after all, only Equity writ large). Otherwise, the State Supreme Courts severally administered justice in every type of case with the keystone of the federal arch available as a general court of appeal.7

The establishment of a bifurcated system had led to large jurisprudential and practical difficulties. A ‘matter’ might be commenced in the ‘wrong’ court and even the Cross-Vesting legislation could not save it8; a State tribunal might be deprived of jurisdiction (and thus a cheap, efficient and just resolution of some minor dispute between the parties) because of the interposition of some federal element.

In his youth in New York, Bullfry had sat (literally) at the feet of Professor Herbert Wechsler, lecturing to a full house in the ninety-first (and last) year of his life. What a masterclass! So popular was it that many late-coming students (including Bullfry) were forced to sit in the aisles. The sage would speak in a broad Brooklyn accent for more than an hour without notes on every aspect of the federal jurisdiction of the United States, drawing constantly on his magnum opus on the topic which ran to some 1200 pages; to keep him on track he deployed a graduate assistant, a Mr Birnbaum (presumably on the Columbia boxing team), whom Bullfry often observed skipping rope in his spare time up and down the steps of the Loeb Library. From time to time as he discoursed:

‘Mr Birnbaum, Mr Birnbaum – I am at page 872, 872’ –

‘Try page 885, Professor’ –

‘Thank you, Mr Birnbaum, thank you’.

But how was it that the American model had fettled the imaginative fires of the Founding Fathers and led to the autochthonous expedient? In the United States, the need for a federal judicial system which stood outside that of the several States of the Union was obvious – at the time of its foundation, and especially after its great internal cataclysm, the need for an overarching system of federal tribunals beholden to the central, not a peripheral, polity to administer disinterested justice was vital.

Even now a federal jury could sentence you to death, though a murder in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts was not so punishable in the State Supreme Court – and partiality in the enforcement of civil rights was a constant danger: ‘Don’t trust yourself to no backwoods Southern lawyer’!

Happily, in our own polity, no prejudiced difference in procedure, substance or choice of presiding officer affected or distinguished the workings of a criminal jury in Cairns, Launceston, or Newcastle. The commercial statutes inherited from England, and the principles of Equity there developed over centuries, applied consistently throughout the Commonwealth.

And it could not be claimed with any sincerity that the Federal Court represented a repository of specific federal expertise (save perhaps in deciding whether a benighted immigrant had delayed too long in filing some application for review). It was quite clear among all cognoscenti that the specialised divisions of the Supreme Court (staffed as they usually were nowadays by expert solicitor-appointees who had devoted a lifetime to, say, corporate arcana) were more than the equal of any federal counterpart.

Sure it was, thought a cynical Bullfry, that the existence of the Federal Court had given the Commonwealth Attorney access to his own appanage to mirror that of the States; but look how that exercise had worked out at the lower level of the federal tribunal devoted to administrative review! ‘Appanage’ had so overwhelmed that system that it had had to be abolished.

And did not the exercise of such ‘appanage’ conceal a lurking and latent danger? The Federal Court was, in essence, the old Court of Exchequer Chamber before which the Commonwealth was a constant plaintiff or defendant. How was the appearance of bias to be deflected when a court’s judicial officers might look to a constant litigant before it for judicial advancement? A ‘panel’ informed the choice of appointment initially, but ultimate ‘promotion’ depended upon one politician alone, no matter how ‘widely’ she (advising Cabinet) had consulted.

Furthermore, there was no permanent Federal Court of Appeal (and one might leave to one side for the moment whether section 77 of the Constitution would permit its creation). More than one-eighty-years ago, Gilchrist Alexander opined that ‘No Court of Appeal which is constituted of judges of concurrent jurisdiction can ever be so good as a court whose judges are appeal judges only’.9 Part of the reason is that on such a court ‘constant exchange of views with the best brains of the country in the tribunal, must have an extraordinarily stimulating and educative effect on even the most distinguished men’.10 Members of a full court inevitably included the odd halt or lame jurist who was a burden to his comrades, not least because a failure over many months to produce a judgment brought the whole ‘team’ into disrepute.

It is way too late now to transfer the judges and the jurisdiction of the Federal Court back to their rightful home in the State Supreme Courts. The autochthonous expedient cannot be dismantled. The complications of federal jurisdiction will only grow more severe as lower courts try to apply the subtle distinctions and amorphous ‘tests’ contained in the leading judgments, and determine the constituent disparate elements of the relevant ‘matter’.

Sir Zelman Cowen’s pious hope, expressed in the Introduction to his first edition of his famous treatise, that issues of federal jurisdiction should be confined ultimately to the pages of legal history, was foredoomed to failure. Advocates, unaware, will go on ventilating federal questions (like M Jourdain speaking prose) without being aware of the jurisdictional snares and toils lurking silently in even the most innocuous facts to the horror of litigants who bear the costs of them, and appellate judges who need to disentangle them. BN

ENDNOTES

1 [2022] HCA 16.

2 ‘So, if a tramp about to cross the bridge at Swan Hill is arrested for vagrancy and is intelligent enough to object that he is engaged in interstate commerce and cannot be obstructed, a matter arises under the Constitution. His objection may be constitutional nonsense, but his case is at once one of Federal jurisdiction. In all three instances, even if it had happened that a police magistrate alone had dealt with them, an appeal would lie from his order to the High Court’: Mr Dixon KC giving evidence to the Constitutional Royal Commission in 1927 at p 788.

3 [2022] HCA at [37].

4 [2022] FCAFC 98 at [86].

5 Malecki v Macko [2022] FCA 766 at [20] – [27].

6 Thurin v Krongold Constructions (Aust} Pty Ltd [2022] VSCA at [65] – [120]; Allianz Australia Insurance Ltd v Probuild Construction (Aust) Pty Ltd [2023] NSWCA 56 at [13] per Leeming JA.

7 The position is fully explained by Edelman J in A-G (Cth) v Huynh [2023] HCA 13 at [207] – [209] in relation to the period both before the enactment of the federal Judiciary Act 1903, and subsequently to it when section 39 of the Judiciary Act operated.

8 Consider the forensic catastrophe of Page v Sydney Seaplanes. A seaplane crashes on take-off killing all aboard it; proceedings are commenced in the Federal Court notwithstanding there is no intrastate element to the flight so the Federal statute cannot apply; the application is dismissed for want of jurisdiction: Page v Sydney Seaplanes [2020] FCA 537 (Griffiths J); the Cross-Vesting legislation is invoked: Page v Sydney Seaplanes [2020] NSWSC 1502 (Adamson J); but on appeal despite the apparent express words of the statute is found not to apply so that the matter may not now be maintained in the Supreme Court since it was statute-barred: Sydney Seaplanes v Page [2020] NSWCA 204; an application for Special Leave is dismissed by consent: [2022] HCAT 154!

9 Gilchrist Alexander, The Temple of the Nineties (1938) p 171.

10 Id. P 173.