- Winter 2022

- Avarice of the ambidexter and other infelicities of the rogue advocate – a truncated history of the medieval origins of barristers’ ethical obligations. A long tradition of a peculiar position

Avarice of the ambidexter and other infelicities of the rogue advocate – a truncated history of the medieval origins of barristers’ ethical obligations. A long tradition of a peculiar position

In Ziems v The Prothonotary of the Supreme Court of New South Wales,1 Kitto J spoke of the ‘peculiar position’ and functions of a barrister as part of ‘a long tradition’ of a relationship of ‘intimate collaboration’ with the bench and other members of the bar in the endeavour of making successful the service of the law to the community. Throughout English history, the formal articulation of legal ethical standards distinguished between the various species of lawyer.2 At least two broad distinctions in that regard may be noted. First, between the ecclesiastical lawyers and lawyers practising in the English lay courts and, second, between pleaders (or countors), serjeants, and barristers, on the one hand, and attorneys and subsequently solicitors, on the other.3 Andrews notes that although many individual standards purported to address the conduct of only a specific type of lawyer, the basic ethical standards, when taken as a whole, did not vary substantially between the various categories of English lawyers.4

Many of the ethical obligations imposed upon advocates and lawyers were largely reactionary. Rose, for example, observes that by the end of the thirteenth century, there was dissatisfaction with the justice system and, in particular, its officials such as judges, sheriffs, and clerks.5 In 1289, a commission of inquiry into judicial corruption resulted in the removal of all the King’s Bench justices and all but one of the Court of Common Pleas.6 This negative popular sentiment was not restricted to court officials but also extended to the legal profession. Political songs ridiculed and satirised lawyers and judges alike. A fourteenth century poem7 sums up the negative sentiment:

And counters [pleaders] on the Bench that stand by the bar,

They will beguile you in your hand unless you beware

He will take 40 pence to take down his hood8

And speak for you a word or two and do you little good

I warrant.

Attorneys in country, they get silver for naught

They make men begin what they never had thought;

And when they come to the ring, they hop if they can.

All they can get that away, they think all is won for them

With skill

No man should trust them, so false they are in the bile.9

A general belief existed that there were an excessive number of lawyers generating an excessive amount of litigation causing unnecessary harm.10 Attorneys and pleaders alike ‘came under the lash of public scorn and indignation’ with ‘a monotonous outcry’ against their misconduct.11 It was such public sentiment that created a climate conducive to regulation.12

Origins of a ‘peculiar position’

The precise origins of the professional bar in the English-speaking world are, surprisingly, obscure and can only be traced imperfectly.13 Cohen traces the bar’s roots to ancient Rome drawing a distinction between the advocati (advocates) and the patroni (pleaders).14 At least by Cicero’s time, the bar in Rome had become a profession whose practitioners were susceptible to discipline by the praetor (ruling governor).15 Cohen observes that ‘it seems’ there is no trace of the professional lawyer in ‘Anglo-Saxon’ England prior to the Norman conquest – postulating instead that the causidici were likely the first known English lawyers. By the thirteenth century, the English common law courts usually permitted the appearance of professional pleaders or ‘narrators’ who conducted the oral pleadings and argued questions of law on behalf of clients.16 The narrators were distinguished from the attorneys, who represented clients in both litigious and non-litigious matters. Interestingly, the pleaders were not regarded as officers of the court and, indeed, modern-day barristers in England are not so regarded.17 Even so, the relationship between bench and bar was nevertheless an intimate one. Members of the bench were invariably appointed from the ranks of serjeants-at-law and considered themselves as belonging to an order – addressing each other as ‘brother.’18 Appointment to the bench did not mean any cessation of membership of the order; on the contrary, because it was regarded as essential that a member of the bench be appointed from this order, it became common in later days to appoint a barrister as a serjeant-at- law merely as a precursor to an immediate appointment to the bench and is why until recent times judges commonly addressed each other as ‘brother.’19

During the reign of Edward I (1272– 1307), a species of elite pleaders emerged known as the ‘serjeants-at-law’20 or ‘serjeants of the coif’21 – the coif being a reference to the distinctive close-fitting hood marking the station of serjeant.22 The expression ‘serjeant’ derived from its Latin appellation *‘Servientes ad legem.’*23 Chaucer described the serjeant- at-law in the prologue to the Canterbury Tales, where the serjeant is addressed as the ‘Sire Man of Lawe’ in flattering terms:

A serjeant of the law, ware and wise, That often had been at the parvis24, There was also full rich excellence, Discreet he was and of great reverence,

He seemed swiche; his words were so wise justice he was ful often at assize,

By patent, and by pleine commission, For his science, and for his high renown,

Of fees and robes had he many on.

By the fourteenth century, ‘apprentices’ emerged as a group of pleaders who were entitled to appear in courts, other than in the Common Bench, on their own and to plead on behalf of clients.25 Also by around this time, organised legal education for apprentices existed which led to the formation of the Inns of Court.26

Thus, the ‘apprentices-at-law’ were, generally, the precursor to modern-day junior counsel, while the serjeants could be said to be the equivalent of today’s senior counsel. For most of the middle ages, these apprentices essentially formed what we now refer to as the junior bar, the actual word ‘barrister’ not being found in use prior to the fifteenth century.27 According to Baker, the title ‘barrister’ originated to denote the position occupied at moots, and had no direct connection with the bar.28 In the seventeenth century, the term ‘barrister’ came into general use in place of the older ‘apprentice at law’ where it is first heard of in connection with utter (or outer) barristers.29

Oaths in English ecclesiastical courts

The ecclesiastical courts of England were likely the first medieval courts to formally set standards of conduct for legal advocates doing so through the use of oaths.30 Use of oaths as a form of regulation is an ancient tradition.31 Advocates in ancient Rome, for example, were required to take an oath, which included obligations ‘to avoid artifice and circumlocution’ to ‘only speak that which he believed to be true’ and to not use ‘injurious language or malicious declamations against his adversary’ or ‘any trick to prolong the cause.’32

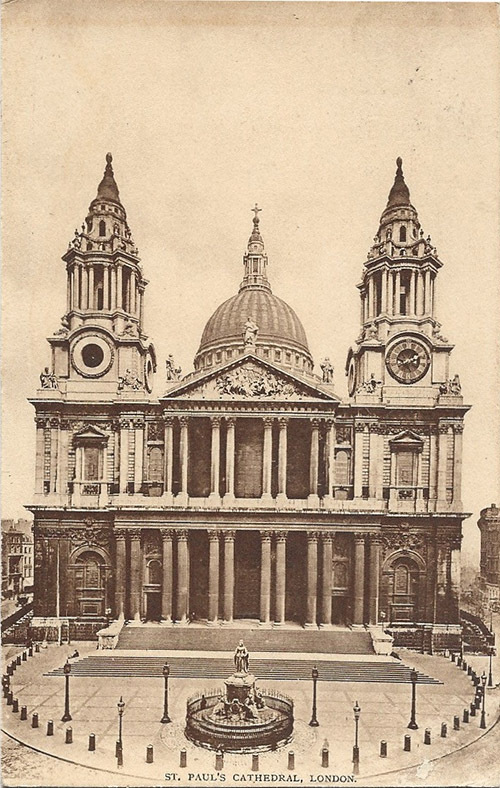

The ecclesiastical courts revived the ancient practice of the advocate’s oath in the early thirteenth century in respect of professional lawyers with the introduction of the St Paul’s advocate oath. In 1237, the council in St Paul’s, London, decreed an oath for ecclesiastical advocates that addressed their litigation conduct.33 The oath required an advocate to swear that he ‘will plead faithfully, not to delay justice or to deprive the other party of it, but to defend his client both according to law and reason’ and also provided that advocates who ‘suborn witnesses, or instruct the parties to give false evidence, or to suppress the truth’ would be suspended from office and subjected to additional punishment for repeated violations.34 The St Paul’s advocate oath was amended throughout the thirteenth century, although certain core principles remained largely intact.35 Most notably, in 1273, Archbishop Kilwardy introduced a detailed oath for advocates in the Court of Arches in London which retained litigation fairness as its central theme by requiring advocates to reject unjust causes, to not seek unjust delays, and to not knowingly infringe on ecclesiastical liberties.36 The oath also added duties owed to the client by requiring advocates to swear that they would diligently and faithfully serve their clients, not charge excessive fees, and not take a stake in the litigation.37 By the fourteenth century, lawyers in the ecclesiastical courts of England were subjected to a broad range of professional standards including litigation fairness and candour, diligence, reasonable fees and service to the poor. 38

Early standards for advocates in non-ecclesiastical courts – the first Statute of Westminster of 1275

The first statute to regulate the conduct of advocates took the form of Chapter 29 of the first Statute of Westminster in 1275 during the reign of Edward I.39 Chapter 29, entitled ‘Deceits by Pleaders’ was a response to reported abuses by lawyers for their lack of candour and provided for imprisonment of ‘any serjeant-countor or other’ who was guilty of ‘any manner of deceit or collusion’ in the king’s courts. 40 The courts interpreted the prohibition on ‘deceit and collusion’ broadly, including applying the prohibition to conflicts of interest or ‘ambidexterity’41 as it was known during the middle-ages. Rose explains that ambidexterity was a common form of medieval lawyer misconduct and was sufficiently ubiquitous to prompt significant adverse public reaction.42 Serjeants, in particular, were often accused of ‘taking fees from both sides’43 and accordingly being an ‘ambidexter.’ In implementing the loyalty duties, the cases also reveal the sensitivity of medieval conflict of interest norms to the need to protect client confidential information.44 Rose gives an example from 1282 of the clients of William of Wells, a serjeant, that, although they had retained and paid William, he failed to assist them. Moreover, in deception of them, after he understood their counsel (‘consilium’), he attached himself to the opposite side without their leave.45

In addition to statutory prohibitions, the serjeants also took a general oath of office. According to Coke, serjeants took the following oath:

That he shall well and truly serve the king’s people as one of the serjeants of the law. That he shall truly counsel them, that he shall be retained with after his cunning. That he shall not defer, tract, or delay their causes willingly, for covetousness of money, or other thing that they may tend to his profit. That he shall give due attendance accordingly.46

A similarly framed oath persisted until the Victorian era, when the order of serjeants itself ceased to exist. 47

The London Ordinance of 1280 and the Ordinance of Edward I of 1292

The London Ordinance was a ‘long, detailed enactment’ regulating both admissions to practice and lawyer conduct in the City of London courts.48 Most relevantly for present purposes, the second section of the Ordinance set ethical ‘duties’ of countors (serjeants). The primary duty of countors was expressed as follows:

… standing, to plead and to count counts, and to make proffers at the bar, without baseness, and without reproach and foul words, and without slandering any man, so long as the court lasts. Nor shall serjeants or attorneys go further in front beyond the bar or the seat where their sitting is; nor shall any one be assessor, or sit near the bailiff, for delivering pleas or judgments, unless it so be that the principal bailiff who is holding the court shall call him unto him; and in such case he shall make oath that he will support neither side.

A duty to prevent conflicts of interest and champerty were also expressly prohibited:

… No countor is to undertake a suit to be partner in such suit, or to take pay from both parties in any action; but well and lawfully he shall exercise his profession.

A subsequent Ordinance of Edward I of 1292 dealt solely with the admission of attorneys and apprentices to the Common Bench.49 The 1292 Ordinance expressly recognised apprentices as a distinct part of the profession and, in so doing, was likely the initial development leading to the Inns of Court and present-day barristers.50

Of significance is the implementation of a quota on the number of apprentices entitled to practise in the Common Bench, in an attempt to restrict the then perceived excessive number of lawyers. The Ordinance specifically empowered the Lord Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas and the rest of his fellow justices

according to their discretions, should provide and ordain, from every county, certain attorneys and lawyers, of the best and most apt for their learning and skill, who might do service to his court and people; and that those so chosen only and no other, should follow his court and transact the affairs therein ….5

The role of the Inns of Court

The serjeants-at-law also constituted the governors of each of the Inns of Court, the so called ‘Benchers’ of the respective Inns, who possessed disciplinary power over members of their respective Inns.52 That power was delegated from the judges of the High Court of Justice, and appeals from disciplinary decisions of the Benchers of an Inn were to the High Court judges sitting as ‘visitors’ and not as a court of law (and remain so to this day).53 Over time, the judges eventually accepted the work of the Inns as machinery enabling the judges to be satisfied as to the fitness of a person to have right of audience in the courts.54 The work of the Inns gave rise to a duty on their part to admit to the bar only fit and proper persons and to suspend or prohibit from practice any member of the Inns who after call to the Bar of the Inn ceased to be a fit and proper person to have right of audience.55 With respect to discipline, the barrister was directly under the control of the respective inn which had called him to the bar. He could be disbarred either by the benchers of his inn or by the judges. Judges, however, seldom acted and parliament made no attempt to displace or supplement the control of barristers by the Inns of Court. In contrast, the attorneys were strictly regulated both by parliament and by the judges.56

Mirror Des Justices

An enigmatic contemporaneous publication believed to have been written about 1285,57 known as the Mirror Des Justices or Mirror of Justices, is also believed to set out the ethical standards of sergeants. Scholars dispute the appropriate characterisation of this work, some calling it a treatise and others calling it a critique or parody of lawyers.58 Even so, the Mirror sets out the duties of a pleader which are corroborated with other contemporaneous materials, such as the 1275 statute and 1280 London Ordinance.59 Andrews explains that the Mirror explained four essentials of the business of a pleader or serjeant.60 The first dealt with qualifications for practice which were largely framed in a negative fashion:

… no heretic, nor excommunicate, nor criminal, nor man of religion, nor woman, nor ordained clerk above the order of subdeacon, nor beneficed clerk with the cure of souls, nor infant under twenty-one years of age, nor judge in the same cause, nor open leper, nor man attained of falsification against the laws of his office.61

The second was the oath of general candour sworn by a serjeant that he ‘will not knowingly maintain or defend wrong or falsehood, but will abandon his client immediately that he perceives his wrongdoing.’62

The third essential elaborated upon the serjeant’s duties of fairness and candour in litigation as well as duties of competence and loyalty

–that he will never have recourse to false delays or false witnesses, and never allege, proffer, or consent to any corruption, deceit, lie, or falsified law, but loyally will maintain the right of his client, so that he may not fail through his folly, or negligence, nor by default of him, nor by default of any argument that he could urge; and that he will not by blow contumely, browl, threat, noise, or villain conduct disturb any judge, party, serjeant, or other in court, nor impede the hearing or the course of justice.63

The fourth essential expounded the duty of the serjeant to set reasonable fees, including the criteria that he should consider in setting his fees – ‘the amount of the matter in dispute, the labour of the serjeant, his value as a pleader in respect of this (learning), eloquence, and repute, and lastly the usage of the court.’64 Likewise, the broader ethical standards of serjeants were presented in speeches given to and by serjeants. Indeed, such academic discourse likely was the most common method by which serjeants passed on the ‘received wisdom’ of proper conduct.65 These speeches, among other things, implored serjeants to abide by ethical obligations such as truth in litigation, exploring settlement alternatives before filing suit, and serving the poor.66

Final comments

Readers will no doubt immediately recognise parallels between current ethical obligations imposed on advocates and those obligations emanating from medieval England. No doubt also recognisable is the public’s mistrust of the legal profession, which unfortunately persists to this day in England67 and Australia68, among other countries. This article will hopefully remind readers of the importance of ethical obligations and their role in seeking to maintain and, ideally improve, the public’s confidence in the administration of justice and the legal profession generally. BN

ENDNOTES

1 Ziems v The Prothonotary of the Supreme Court of New South Wales (1957) 97 CLR 279 at 298 per Kitto J.

2 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1389.

3 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1389.

4 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1389.

5 Jonathan Rose, ‘Medieval Attitudes toward the Legal Profession: The Past as Prologue’ (1998) 28 Stetson Law Review 345, 348.

6 Jonathan Rose, ‘Medieval Attitudes toward the Legal Profession: The Past as Prologue’ (1998) 28 Stetson Law Review 345, 348.

7 Poem on the Evil Times of Edward II as reproduced in Thomas Wright, Thomas Wright’s Political Songs of England (Cambridge University Press, 1st ed, 1996) 323.

8 Referring to the distinctive hoods or coifs worn by serjeants-at-law: see endnote 18 below.

9 Poem translated by Dr. Robert Bjork, who believes that ‘bile’ may mean ‘bille’ or legal document, which would be more plausible than ‘beak’ as a metaphor for ‘face.’ It may also mean ‘bile,’ as in yellow or black bile, although this may be too complicated an allusion. Thus, Bjork believes it is a misspelling of ‘bille.’

10 Jonathan Rose, ‘Medieval Attitudes toward the Legal Profession: The Past as Prologue’ (1998) 28 Stetson Law Review 345, 350.

11 Jonathan Rose, ‘Medieval Attitudes toward the Legal Profession: The Past as Prologue’ (1998) 28 Stetson Law Review 345, 350 citing G.O. Sayles, Select Cases in the Court of King’s Bench under Edward I (Selden Society, 1936).

12 Jonathan Rose, ‘Medieval Attitudes toward the Legal Profession: The Past as Prologue’ (1998) 28 Stetson Law Review 345, 349–350.

13 KMB v Legal Practitioners Admissions Board (Queensland) [2017] QCA 146 at [4] per Sofronoff P.

14 Herman Cohen, ‘Origins of the English Bar’ (1914) 30(4) Law Quarterly Review 464, 464.

15 Herman Cohen, ‘Origins of the English Bar’ (1914) 30(4) Law Quarterly Review 464, 464 citing Abel Hendy Jones Greenidge, The Legal Procedure in Cicero’s Time (Clarendon Press, 1901) 148.

16 KMB v Legal Practitioners Admissions Board (Queensland) [2017] QCA 146 at [5] per Sofronoff P citing Richard Clive Teece, The Law and Conduct of the Legal Profession in New South Wales (Law Book Co. of Australasia, 1963) 1.

17 KMB v Legal Practitioners Admissions Board (Queensland) [2017] QCA 146 at [5] per Sofronoff P citing Richard Clive Teece, The Law and Conduct of the Legal Profession in New South Wales (Law Book Co. of Australasia, 1963) 2.

18 KMB v Legal Practitioners Admissions Board (Queensland) [2017] QCA 146 at [8] per Sofronoff P.

19 KMB v Legal Practitioners Admissions Board (Queensland) [2017] QCA 146 at [8] per Sofronoff P.

20 Jonathan Rose, ‘Legal Profession in Medieval England: A History of Regulation’ (1998) 48 Syracuse Law Review 1, 7.

21 Jonathan Rose, ‘Legal Profession in Medieval England: A History of Regulation’ (1998) 48 Syracuse Law Review 1, 7.

22 J.H. Baker, The Legal Profession and the Common Law: Historical Essays (Hambledon Continuum, 1986) 78.

23 E Douglas Armour, ‘Law and Lawyers in Literature’ (1927) 5(4) Canadian Bar Review 265.

24 It is said that both at Westminster Abbey and St. Paul’s there was a parvis at which the serjeants took their walks and saw their clients. Similarly, it was the custom of the Roman Bar to walk the Forum to give advice: The Office of Serjeant-at-Law, 3 FORUM 16 (1875).

25 Theodore F.T. Plucknett, The Place of the Legal Profession in the History of English Law, 48 Law Quarterly Review 328, 336.

26 Jonathan Rose, ‘Legal Profession in Medieval England: A History of Regulation’ (1998) 48 Syracuse Law Review 1, 33.

27 W. Boulton, ‘The Legal Profession in England: Its Organization, History and Problems’ (1957) 43 American Bar Association Journal 507, 508.

28 J.H. Baker, ‘Counsellors and Barristers. An Historical Study’ (1969) 27(2) The Cambridge Law Journal 205, 214–215.

29 Roscoe Pound, ‘Legal Profession in England from the End of the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century’ (1944) 19(4) Notre Dame Law Review 315, 318.

30 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1392.

31 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1393.

32 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1393.

33 Josiah Henry Benton, The Lawyer’s Official Oath and Office (The Boston Book Company, 1909) 14–15.

34 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1393.

35 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1393.

36 Paul Brand, The Origins of the English Legal Profession (Oxford University Press, 1992) 147.

37 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1393.

38 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4)SMU Law Review 1385, 1394.

39 Statute of Westminster the First 1275 (3 Edw I) ch 29.

40 Edward Coke, The Second Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England (W. Rawlins, 1681) 212–213. See also Jonathan Rose, ‘The Legal Profession in Medieval England: A History of Regulation’ (1998) 48 Syracuse Law Review 1.

41 Jonathan Rose, ‘The Ambidextrous Lawyer: Conflict of Interest and the Medieval and Early Modern Legal Profession’ (2000) 7 University of Chicago Law School Roundtable 137, 145–146.

42 Jonathan Rose, ‘The Ambidextrous Lawyer: Conflict of Interest and the Medieval and Early Modern Legal Profession’ (2000) 7 University of Chicago Law School Roundtable 137,139.

43 Jonathan Rose, ‘The Ambidextrous Lawyer: Conflict of Interest and the Medieval and Early Modern Legal Profession’ (2000) 7 University of Chicago Law School Roundtable 137,139.

44 Jonathan Rose, ‘The Ambidextrous Lawyer: Conflict of Interest and the Medieval and Early Modern Legal Profession’ (2000) 7 University of Chicago Law School Roundtable 137, 154.

45 Jonathan Rose, ‘The Ambidextrous Lawyer: Conflict of Interest and the Medieval and Early Modern Legal Profession’ (2000) 7 University of Chicago Law School Roundtable 137, 154.

46 Edward Coke, The Second Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England (W. Rawlins, 1681) 212–213.

47 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1397.

48 Jonathan Rose, ‘The Ambidextrous Lawyer: Conflict of Interest and the Medieval and Early Modern Legal Profession’ (2000) 7 University of Chicago Law School Roundtable 137, 146.

49 Jonathan Rose, ‘Legal Profession in Medieval England: A History of Regulation’ (1998) 48 Syracuse Law Review 1 at 80ff.

50 Jonathan Rose, ‘Legal Profession in Medieval England: A History of Regulation’ (1998) 48 Syracuse Law Review 1, 79.

51 SKMB v Legal Practitioners Admissions Board (Queensland) [2017] QCA 146 at [12] per Sofronoff P.

52 KMB v Legal Practitioners Admissions Board (Queensland) [2017] QCA 146 at [9] per Sofronoff P.

53 KMB v Legal Practitioners Admissions Board (Queensland) [2017] QCA 146 at [10]–[11] per Sofronoff P. See also Re S (a barrister) [1969] 1 All ER 949 at 951; [1970] 1 QB 160 at 166; Re S (a barrister) [1981] 2 All ER 952 at 953; [1981] QB 683 at 685.

54 Re S (a barrister) [1970] 1 QB 160 at 174–175. See also Frederick Pollock, ‘The Origins of the Inns of Court’ (1932) 48 Law Quarterly Review 163.

55 Re S (a barrister) [1970] 1 QB 160 at 174–175.

56 Roscoe Pound, ‘Legal Profession in England from the End of the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century’ (1944) 19(4) Notre Dame Law Review 315 at 317.

57 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1398.

58 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1398.

59 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4)SMU Law Review 1385, 1398.

60 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4)SMU Law Review 1385, 1398.

61 The Mirror of Justices (Selden Society, 1893) 46.

62 The Mirror of Justices (Selden Society, 1893) 48.

63 The Mirror of Justices (Selden Society, 1893) 48.

64 The Mirror of Justices (Selden Society, 1893) 48.

65 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1398–1399.

66 Carol Rice Andrews, ‘Standards of Conduct for Lawyers: An 800-Year Evolution’ (2004) 57(4) SMU Law Review 1385, 1398–1399.

67 Jonathan Goldsmith, ‘Beware the growing mistrust in lawyers’, The Law Society Gazette (online, 22 May 2018) <https://www. lawgazette.co.uk/commentary-and-opinion/beware-the-growing- mistrust-in-lawyers/5066215.article>.

68 Felicity Nelson, ‘Public continues to distrust lawyers’, Lawyers Weekly (online, 29 April 2015) <https://www.lawyersweekly.com.au/ news/16450-public-continues-to-distrust-lawyers>.