- Winter 2024

- An interview with Keith Mason and Larissa Reid

Keith Mason AC KC and Larissa Reid spoke to Bar News about the drafting and publishing process behind Constant Guardian, Changing Times – The Supreme Court of New South Wales 1824–2024, their illustrated history of the Supreme Court of New South Wales in celebration of its bicentenary.

Bar News (BN): When did the concept of the book arise?

Keith Mason AC KC (KM): Five years ago, not long before Tom Bathurst ended his term as chief justice. I jumped at the idea of ‘writing’ a history of the court. I had just finished the Jordan biography. A 2024 bicentenary deadline then seemed a long time away. I would soon learn that the exercise needed to become a highly collaborative one because it was going to be thematic, with some specialist contributors. I would also quickly discover how much research remained to be done, especially covering the last 50 years since John Bennett’s History that had been written for the sesquicentenary.

When it was realised that there should also be lots of pictures, I was already well out of my comfort zone, really out of my depth.

BN: Keith, what were the interactions between you, the chief justice and Larissa in putting the chapters together?

Keith Mason AC KC (KM): After Andrew Bell became chief justice in early 2022, he and I decided to attack the project with a small committee (of two) in lieu of the original consultative committee of about seven judges. Larissa, who manages the research team at the Law Courts Library, was by then coordinating and assisting with my growing number of research queries. At the CJ’s request, she also assumed the role of investigating what pictures and newspaper clippings might be ‘out there’.

It soon became apparent that Larissa and I were assuming editorial roles in addition to our particular tasks of writing, researching and (in Larissa’s case) assembling pictures. For example, draft chapters sometimes overlapped. They all needed detailed fact-checking. Stylistic bumps had to be ironed out. Decisions were being constantly made, choosing consultants to read drafts and responding to their suggestions. Material was sometimes moved from one chapter to another. The contributing authors very generously gave us a free hand to make changes as the character of the book emerged.

In some cases, a smallish draft chapter by one person would be expanded by contributions from others.

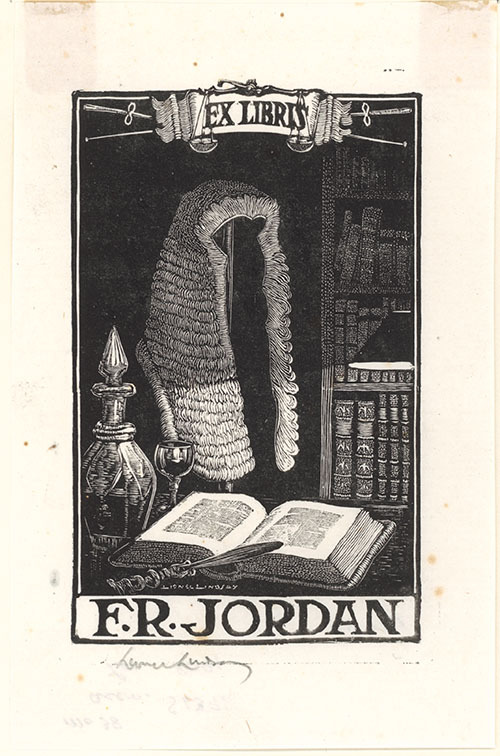

Larissa Reid (LR): The art chapter is a good example of this – Justice Sackar wrote a lovely piece about the portraits held by the court, interactions with the Archibald Prize, artworks around the court and [he] touched on the topic of court artists. The Chief Justice added a section on paintings of the court (including one depicting a cricket match in Hyde Park with the court in the background, see p 334–335) and Lee Aitken and Jim Poulos’ collaboration on the Bullfry pieces for Bar News. Keith expanded the section on the Archibald Prize cases and investigated other cases involving art; we also found a great account by Justice Sheller of the re-enactment of the Dobell trial for the 175th anniversary. I added a section on sculpture, vignettes about the friendship between Sir Frederick Jordan and Sir Lionel Lindsay (inspired by the beautiful woodcut bookplate that Lindsay made for Jordan, see pp 347) and Roddy Meagher’s Portraits on Yellow Paper and expanded the section on court artists. Sophie Howard, the court’s Bicentenary Project Officer, gave us an art history perspective to put it all into context.

KM: Chief Justice Bell took a very active role throughout the project. He read every draft chapter several times and made material contributions from the outset. He and I co-wrote the final chapter, entitled ‘Open Justice’. There are reflections upon the changing role of the modern chief justice in chapter 2.

LR: The Chief Justice also wrote several vignettes about his predecessors and added personal touches to many other chapters. There is such a warmth and generosity in the way he talks about judges and practitioners, and you can hear this in every speech he has given.

BN: Larissa, were there other significant individuals who assisted in the production of this work?

LR: One of the best things about this project has been its collaborative nature and the enthusiasm of all involved. The staff of the Law Courts Library provided exceptional research and moral support (and a steady supply of snacks). Sophie Howard has a terrific artistic eye and helped shape the visual style of the book. She also designed the chapter motifs, which are based on decorative elements from the King Street Courts. Philippa Breaden and Kate Lumley from the Judicial Commission did the copyediting and made many helpful suggestions along the way. Chris Winslow, the court’s media manager, calmly managed all the logistics of production and ensured we met the deadline. He was also one of our best ‘readers’ – I remember one time he plucked a paragraph out of the middle of a chapter and said, ‘That’s your lead’, and he was absolutely right.

We wanted the book to be accessible and engaging and were extremely fortunate to have so many judges, barristers, academics, court staff and family members willing to read draft chapters and provide feedback. For example, Associate Professor Heather Roberts (who has pioneered the study of swearing-in ceremonies) made detailed comments on several chapters and spent hours talking about different directions for the book. Andrew Smith’s thoughtful comments on the Indigenous peoples chapter really deepened my understanding of the subject matter and I was delighted that he was invited to deliver the Acknowledgement of Country at the ceremonial sitting for the bicentenary.

BN: How were the images collected and captioned?

LR: When Chief Justice Bell asked me to start looking for pictures, he said that he wanted the book to be visually interesting, with a mix of photos, paintings, sculptures, documents and artefacts. The idea was that there would be something interesting on every page. We wanted to capture different time periods, to illustrate the humanity of the court and to show how the institution responded to changes in society and crises.

This was a pretty wide brief, and so I looked everywhere I could think of, starting with the court and Law Courts Library collections, then moving on to other libraries, galleries, archives and museums, and commercial suppliers such as Fairfax and Newspix. I pored over biographies and books about famous cases and histories of the court and legal profession and ran countless internet searches. Sophie was also looking for images for the History Wall and the gallery (both installed on level 13 outside the Banco Court) and so we combined our efforts. The court commissioned photos of the King Street courthouse, historical artefacts and several portraits. Some of the authors had included picture suggestions too, so there was a lot to choose from.

Once the text of a particular chapter was finalised, Sophie, Keith and I would sit down with the images we’d gathered and choose the ones for inclusion in the book. For example, there is a section on judicial dynasties in the ‘Lives of the Judges’ chapter and we wanted to include the Street family. There were several options, including the trio of magisterial oil paintings and some lovely black and white photos, but there was also a most surprising inclusion in Sir Laurence Street’s biographical file in the library. It was a copy of Woman’s Day from 1974 with the most fantastic double-page spread entitled ‘Chief Justice Street – now that sounds familiar … ’ For us, this was the obvious choice – it just captured the moment perfectly. Sophie took charge of obtaining the high-resolution versions with the requisite copyright and cultural permissions (a huge job in itself).

The captions were another collaborative effort, but there were a few which Keith particularly wanted to write – one of my favourites is the photo of Laurence Street CJ (p 298) in the ‘Judicial Commission’ chapter. It was taken on the day of the judges’ meeting about the controversial Judicial Officers Bill, and he has a prominent bandage on his hand. On the facing page is a cartoon featuring a judge with a gavel, looking down sternly at Terry Sheahan, whose hand is clearly smarting. The proximity of these images amused Keith greatly, and his caption says, ‘It is not suggested that retaliation by the Attorney for the injury depicted in the cartoon opposite had any connection with the Chief Justice’s hand injury.’

KM: This also covered our back against a defamation writ from my friend Terry.

BN: Are there any fascinating facts that you learnt about the Supreme Court that you didn’t know before researching the book?

LR: My favourite discovery was the installation of a temporary post office in the King Street Court House as part of the sesquicentenary celebrations. A commemorative stamp had been issued, and for one week in May 1974, you could go along to the court to post a letter and it would be stamped with a special Supreme Court postmark. I was determined to track down the stamps and first-day covers so that we could include a picture of them in the book and could hardly believe it when they turned up on eBay!

KM: One of mine was the prolonged saga of Hocking v Bell (see p 150). From time to time, particular decisions in this mega-litigation were cited in the Court of Appeal on matters such as the ‘scintilla principle’ and the tests for overturning a civil jury verdict. I never knew of the human drama lying behind the litigation. The length of the various hearings is breathtaking (12 days in the High Court, 17 in the Privy Council). The Medical Defence Union was almost bankrupted.

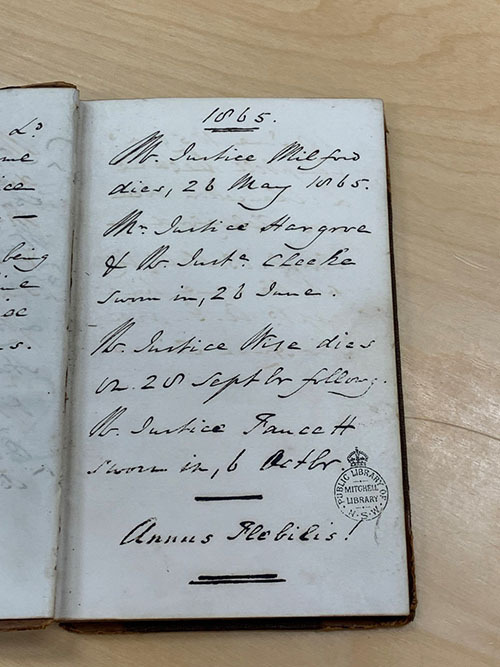

Another was the discovery of a note by Sir Alfred Stephen in his copy of the 1865 Law Almanac. He listed the death of Milford J on 26 May, the swearing in of Hargrave and Cheeke JJ on 26 June, the death of Wise J on 20 September, and the swearing in of Faucett J on 6 October. Annus flebilis [a year to be wept over].

The chapter on the brawling over the creation of the Judicial Commission was also a lot of fun to research and write as we got into the details.

BN: Did you find any extraordinary original documents?

LR: I had been working closely with the staff of the Museums of History NSW in preparation for a trip to the State Archives at Kingswood. When I arrived, they had set up a room for me, and there was a giant three-tier trolley full of documents for me to pore over. The first one I looked at was the original New South Wales roll of barristers and solicitors from 1824. It is quite a large document – more than a metre wide – and there was something really special about seeing these familiar names entered neatly on the roll; the first four were Saxe Bannister, John Stephen, Dr Robert Wardell and William Charles Wentworth.

KM: The New South Wales Bar will learn from the book what colourful characters these men all were. Saxe Bannister was thought by Forbes CJ to be deranged (p 145); Wardell and Wentworth published the colony’s first independent newspaper; Wardell was shot by an escaped convict (p 348); by modern standards, Wentworth would probably have been struck off for his conduct in a particular case (see p 203).

LR: I looked through boxes and boxes of material about the famous ‘Shark Arm’ case. I was amused to see a note attached to the front of the first file that said, ‘Please file in the compactus and let me know where you file it as I have had to produce these papers to the Department on a number of occasions … DO NOT send to Shea’s Creek’ [emphasis in original]. As a librarian who often finds the same questions popping up over time, I could really relate to this. On another document, someone had drawn a cheerful little shark. It was fascinating to read eyewitness accounts of the shark disgorging the arm at the Coogee Aquarium. There was also a tantalising list of exhibits, one of which was ‘photo of arm’, but the photo itself was nowhere to be seen (the wonderful staff later tracked down a copy of it at the Police and Justice Museum) (see p 127).

I had been thinking about the best way to illustrate the account of the Myall Creek Massacre trials, and I had several references to archival documents to investigate, thanks to Professor Bruce Kercher’s work on colonial cases. In the second trial, the foreman of the jury originally said ‘not guilty’, but this was a mistake [and] Justice Burton simply crossed out the ‘not’ in his notes. Seeing it on the page like that was an incredible moment for me. The photo I took that day was used in the book (see p 122).

Keith and I also had a terrific day at the State Library, looking at all sorts of documents, photos, artefacts and so on. Among other things, I had requested a collection of oaths, as I was hoping that at least one of them would have beautiful calligraphy and thus could be used to illustrate the oaths section of the ‘Ceremonies, Robes and Symbols’ chapter. I remember Keith opening them up and whispering excitedly to me, ‘Look at this!’. They were extraordinary – Justice Dowling’s declaration against the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation (p 358), Justice Willis’s oath abjuring the royal title of the Jacobite pretenders to the throne (p 357).

BN: What are your favourite pictures in the book?

KM: For me, the photos of Virginia Bell (p 227), Jim Wood (p 176) and Peter Young (p 78).

LR: So many! I particularly like the photos of Margaret Beazley as junior counsel and Justice Simpson in the women chapter (p 223 and 224); Harold Cazneaux’s atmospheric portrait of Chief Justice Cullen (p 257); the contemplative photo of Justice Chen just before his swearing-in ceremony (p 354); the dashing young Laurence Street QC outside the Voyager Royal Commission (p 270); the moody shot of Andrew Ettingshausen in the locker room (p 146; note that this is not the photo that was found to be defamatory); the 1970s glory of the original foyer of the Law Courts building (p 324–5); Jordan CJ and his colleagues in breeches and buckled shoes (p 368); and of course the ‘shark arm’ (p 127). I’m also quite fond of the yellow paint splash in the section on contempt (p 113).

BN: Any particular difficulties or setbacks?

KM: The Department of Communities and Justice refused access to some of the inflammatory letters written by judges during their campaign against the creation of the Judicial Commission – despite this being as far back as 1986. My review application to the Privacy Commissioner under the Government Information (Public Access) Act was successful (see GIPA reference no IPC23/R00071). Alas, not all of the juicy letters as remembered by Terry Sheahan have yet come to light, but some of them are mentioned in the book.

BN: What were some of the biggest changes in practice at the Bar that are documented?

KM: Chapter 5, ‘Lawyers and Litigants’, includes some interesting material about the relationship between the court and the profession over the years. We discovered that the 1838 admission rules mandated proficiency in Latin and Greek ‘together with a competent knowledge of Arithmetic, and of the first Six books of Euclid’. For a time, barristers had to be first admitted in the United Kingdom. The book also documents the decline of civil juries and the move from exclusively oral to ‘largely’ written submissions. Shifts in the culture of admission ceremonies are also recorded. Naturally, there is material about the contested arrival of women into the profession and the incredible diversity that has emerged in recent decades.

BN: There are some amazing titbits in the book that feel as if they have been told and retold on an informal basis. Can you describe the process by which you collected stories like these?

LR: One thing I wanted to do was to capture as many voices as possible, so that the book felt like a reflection of the community of the court. I’ve always liked attending swearing-in and farewell ceremonies, and you hear a lot of great stories at those. As soon as Justice Beech-Jones made a quip about remaining ‘pen friends’ with the Court of Appeal at his farewell ceremony (on the eve of his appointment to the High Court), we knew that had to go in. I also read speeches, interviews and biographies and many back issues of Bar News, looking for personal stories. The court is an institution, but it is an institution of people.

The vignettes were another way of letting individual voices and personalities shine through. There are a few pieces ‘as remembered’ by various judges, such as Justice Bryson’s recollections of ‘Funnelweb’ Freddie Myers (p 91) and long-term tipstaff Captain Adams (p 268) and Justice Barrett’s memories of his associate, Margaret Newby (p 94). We also included extracts from historical letters and journals to give a flavour of the court at different times, for example Justice Dowling’s account of the opening of the first circuit court in Maitland in 1829 (p 26) and Chief Justice Stephen’s astonishingly frank letter about his colleagues, Justice Hargrave and Justice Cheeke (p 280).

BN: Anything left out or discovered later?

LR: There was an absolutely marvellous photo of Justice Dhanji on stage at an Elastique Mindbladder gig, which had been posted on the band’s Facebook page. We tried to get it for the book, but it had been taken on someone’s phone and the resolution just wasn’t high enough.

KM: The litigation in Egan v Willis (1996) is discussed in the chapter on civil jurisdiction. The Supreme Court was able to address a very important constitutional point about the relationship between the two Houses of Parliament because there had been an ‘assault’ by the Usher of the Black Rod upon a Minister who ‘resisted’ his removal from the Upper House (see the picture at p 155). As counsel for the losing side, I cannot deny that there had been some advance preparation to guarantee the commission of a tort. Very recently I came across a 1999 note that I would have loved to have included as a footnote. A ‘Sydney barrister’ stated that ‘[i]t was, of course, a put-up job. He had been escorted by a prior arrangement. Nevertheless, that was the pleading’ (AIAL Forum No 22, p 39). Since that junior barrister is now the chief justice of the High Court, it would have been fun to have included this as a footnote. I think that the prospects of me (and possibly my opponent, Bret Walker [SC]) being disciplined for participating in an abuse of the processes of the court are now pretty remote.

BN: Any new projects for each of you?

LR: I am working on a project involving English manuscript law reports with Sir John Baker. It is amazing how many cases have never been printed and this project will make it easier for researchers to know what is available.

As a point of comparison, Sir James Dowling, our second chief justice, had been a law reporter in England, and he continued to keep notes of cases when he came to New South Wales. He had intended to publish them, but they remained in manuscript form in the State Archives for more than 160 years. Tim Castle and Bruce Kercher edited the reports, and they were published by the Forbes Society in 2005, and as a result we have been able to learn so much about the early history of the New South Wales Supreme Court and the colony.

KM: Tony Cunneen and I have embarked upon a book about Sir William Cullen who was chief justice between 1919 and 1925.