- Autumn 2023

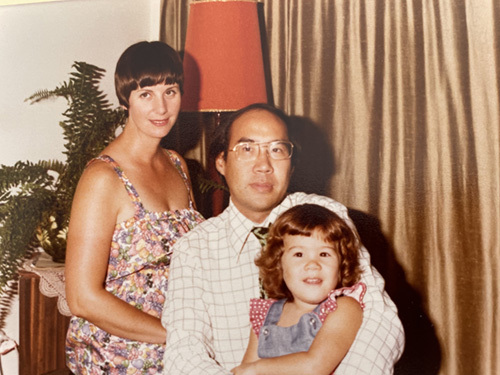

- A classic mixture of multicultural Australia

Tiffany Wong SC joined the Bar in 2003 and was appointed silk in 2019. She has built up a broad public law, commercial and regulatory practice and is regularly briefed to appear in complex trials and appeals. She spoke with Eugene Chan, barrister at New Chambers and member of the NSW Bar’s Diversity and Equality Committee.

Eugene Chan (EC): Tiffany, tell us a bit about yourself and your cultural background.

Tiffany Wong SC (TW): Well, I consider myself to be a classic mixture of multicultural Australia. My mother is a fifth-generation Australian of English, Scottish and Northern Irish ancestry. She grew up in country New South Wales in towns such as Wagga Wagga, Narrabri and Nowra, and she completed her schooling in Newcastle. My father, on the other hand, is of Chinese ethnic descent. His mother was from Guangzhou and his father was of Hainanese ancestry. My father was born in a basement in Singapore during the Japanese occupation in World War II. He did most of his schooling in Singapore but, like many children who were born to the upper middle class in southeast Asia, he was sent overseas to further his education. So he arrived in Sydney at the age of 16 and he did his leaving certificate at Enmore Boys High. He then swept floors at a Coca Cola factory and put himself through medical school at Sydney University. He met my mother who was training to be a nurse in a hospital in Newcastle.

My cultural background can be described as ‘Asian Australian’. However, because I have one parent of Asian ancestry and another of European, I could be described as ‘Eurasian’, but I don’t hear many people use that description these days.

EC: Growing up, did you ever feel like an outsider or that you were different from other kids because of your cultural background?

TW: Well, from time to time, I got an awkward question in the schoolyard like ‘Where do you come from?’. I had a standard answer that I would always give, which was ‘From Australia’ – full stop – and then the poor child who asked me would say, ‘No, no, I didn’t mean that’. They would then reframe the question, and say ‘I meant, where do you really come from?’ or ‘Where do your parents come from?’. And then I’d give them the answer which I knew that they were actually looking for, which was to explain where my father came from. I would also tell them that my mother was Australian. But, aside from this, at the schools that I went to, there were lots of kids of migrants. They were from a range of different countries and that was the ‘cultural mixing-pot’ that Sydney, or at least the part of Sydney that I grew up in, had become by the 1980s and 1990s.

I was also exposed to a range of different cultures through my parents. They owned a pathology lab in the Inner West for much of my youth and they were equal opportunity employers. They employed people from literally all over the world as pathologists, lab assistants, couriers and clerks. Some of them could only speak a few words of English when they started the job, and my father could make small talk in at least 10 different languages – some of these were European. My parents had friends and business associates from many different migrant communities – the Greeks, Italians, Jewish, Vietnamese – and, of course, there were the very strong ties that my father had with the Chinese-Australian community and the many cousins who had come to Australia from Singapore just like him. My parents also did business with a lot of Aussies in regional Australia and elsewhere.

So, as a child, I had quintessential Australian experiences like holidaying at the beach and 40-degree Christmases in the bush with my mother’s family, as well as Chinese family gatherings with hundreds of sticks of satay and attending bar and bat mitzvahs. My favourite events were the combination Chinese and European weddings, when one of the kids of my Dad’s cousins married someone who wasn’t Chinese. So I never really questioned the fact that I was literally straddling these different cultures. It was just how it was when I was growing up. Some kids brought cakes to schools for their birthdays; I brought prawn crackers, and everybody loved them.

Those were the positive aspects of my multicultural upbringing. As for the negatives – well there is no doubt at all that many migrants, children of migrants and other cultural minorities within Australia experience terrible racism. For me, I think I was just lucky. I blended into the mainstream when I was a child, and I don’t think I was held back that much growing up by my cultural background. Then again, I did experience bullying in the legal workplace, not so much at school. At the time, I didn’t attribute that particularly to any cultural difference that might have existed. I just thought it was a very worrying side-effect of the hierarchical nature of the Australian legal profession. When I read the newspaper now, I see a range of different types of racism still occurring in Australia towards cultural minorities, which is very troubling. A couple of recent examples are the treatment of the Australian cricket commentators, Bharat Sundaresan and Andrew Wu.

When I started to look around, I saw change. There were a lot more barristers from many different cultures.

EC: Your dad has a medical background. What made you choose to join the legal profession and why specifically come to the Bar?

TW: Traditionally, of course, the only acceptable profession of children of Chinese migrants was to be a doctor. But somehow my father knew that I was never going to be a doctor and he didn’t place that particular pressure on me. I don’t know what book it was that I read or movie that I saw but from a very young age, I wanted to be a lawyer. And I actually wrote an autobiography at the age of 11 where I said on the last page that I wanted to be a lawyer when I grew up. I was also encouraged to come to the Bar when I worked as a tipstaff to the Hon Keith Mason AC KC, who was at that time the President of the Court of Appeal. He was a real inspiration. While listening to the cases in the Court of Appeal, I came to realise that standing on my feet in court was what I ultimately wanted to do.

EC: When you came to the Bar, do you remember thinking about its complexion and whether there were others who looked like you?

TW: Initially, I was just really happy that Seven Wentworth had agreed to take me on as a reader in 2003. I knew that it was a floor that had many highly regarded barristers, very senior barristers at that time including David Jackson QC and Robert Stitt QC, and some up-and-coming luminaries, like Justin Gleeson SC and Richard White SC, and so I didn’t think too much about diversity. I took it as a given that I was going to be surrounded by white Australian males. My expectations were, at least on a diversity level, fairly low, but tempered by the fact that I was going to be around so many people who were so talented, experienced and knowledgeable in the area that I wanted to practise in.

A few years later, I did start to wonder whether there were any other Asians at the Bar. I looked online on the ‘Find a Barrister’ website and there seemed to be two others with a similar last name to myself. As a matter of personal observation, I knew that there were not that many Asian barristers. This was in the mid to late 2000s.

EC: Do you still think about, or have you reflected upon the complexion of the Bar, now?

TW: After I did that initial survey I didn’t think about it again for some time. I seemed to be making some headway at the Bar. I was just really glad that people were briefing me. Senior barristers seemed to think that I had something to offer in terms of the work I could do for them. There were some barristers who really helped me in my early career at the Bar who didn’t seem to be concerned at all about what my cultural background or gender might be. Justin Gleeson SC was a fantastic mentor and involved me in many of his interesting cases and, in fact, there were a lot of senior barristers from Seven Wentworth and Banco Chambers who made it a priority to work with junior barristers regardless of having any connection with them or not. It was part of the culture that existed back then, that they would try to give work to every single reader on the floor, in order to give them a kickstart to their career. About five or six years ago, I did begin to notice that people were starting to talk more about diversity. There was the NSW Diversity Survey in 2018, as well as the famous Bar News diversity issue in 2019 which summarised the results of the survey and had the much talked about cover that showed a number of the diverse members of the NSW Bar. In 2019, I also joined the ABA’s Diversity & Inclusion Committee, chaired by Kate Eastman AM SC who has done much wonderful work in this area.

When I started to look around, I saw change. There were a lot more barristers from many different cultures. There were at least a few Indigenous barristers, certainly not enough having regard to the Census results which I want to talk about later. From when I commenced at the Bar, there had always been barristers who identified as LGBTQI+ but I could see that the proportion of people who identified as such had increased as well, which was very promising. Far more frequently, I would walk into a mediation or courtroom, and I would not be the only woman or Asian Australian in the room. But still improvements need to be made.

EC: You’ve mentioned already a few types of diversity – Asian Australians, gender and LGBTQI+ – what does racial and cultural diversity mean?

TW: I think it is useful to have some background in terms of what the 2021 Census conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics tells us about cultural and racial diversity in Australia. However, I don’t think statistical analysis is the only way to understand how well our institutions or workplaces are doing in terms of diversity.

The 2021 Census data shows that:

• Over 7 million people in Australia were born overseas, representing 27.6% of the population. This means that more than one in four people you meet in Australia will not have been born here. Of that

27.6%, more than a quarter were born in Asia, the four most common countries of Asian birth being India, China, the Philippines and Vietnam.

• The number of people who were either born overseas, or have a parent born overseas, is greater than half – 51.5%. And in some parts of Sydney, such as Auburn, Fairfield and Parramatta, more than 50% of people were born overseas. Most people will not realise this.

• Overall, there were 320 different ancestries reported and 429 different languages spoken.

• 3.2% of Australia’s population in 2021 were First Nations people, speaking 183 different Australian Indigenous languages.

So it is true to say that Australia is one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse places on the planet. You can obviously measure our institutions and workplaces against this Census data in terms of, for example, how many barristers fit certain criteria in comparison with the Census data. That is one way of measuring cultural diversity, but it doesn’t answer other important questions such as:

• What approach are our workplaces and institutions taking towards diversity and inclusiveness?

• Are we being respectful and open minded towards cultural and other differences?

• How are we making sure that we are valuing the skills and expertise that people of different cultures can bring to our workplaces and institutions?

• What steps are we taking to ensure that people have access to our justice system and where needed, interpreters, having regard to the statistics about the number of different languages spoken in Australia and that many people have English as a second language or don’t speak English well?

• Are we merely tolerating the differences that exist among people of different cultures or are we celebrating them?

Those are some of the matters that we need to consider when talking about cultural diversity.

EC: It’s clear what you’re saying is that all those matters about cultural diversity do have a place at the Bar and on the Bench.

TW: Absolutely. There is momentum towards improving diversity in the broader Australian community. Work done by various NGOs has exposed, for example, the lack of cultural diversity and inclusion of Indigenous Australians on the boards of Australian companies, as well as in terms of authorship of published Australian literature and the number of presenters on Australian news and current affairs programs. There is a broader push, a broader acceptance of the need to have representation of our migrant and Indigenous communities in these institutions that are so important to Australian life. This is also reflected in the approaches taken by the governing bodies of the legal profession. The ABA and the NSW Bar Association have both adopted diversity and inclusion principles, as well as many other State Bar Associations. I do think there is broad support for promoting and strengthening the diversity of our legal profession.

There’s also a push for diversity within our judiciary coming from both inside and outside our courts. From my perspective, one of the most important reasons to have a diverse bench is to enhance the legitimacy of our courts – there is a very good speech written by Justice Dhanji1 where he explained that increasing the diversity of our judicial officers reduces the gap between those being judged and those doing the judging. It is also the case that a diverse bench may bring about a reduction in unconscious bias. I like the terminology used by the academic, Brian Opeskin,2 that greater diversity will ‘replace one dominant norm with a plurality of cross-cutting affiliations’ that will help to reduce systemic bias overall. We strengthen our democracy by having a diverse judiciary and I think very good steps have been taken in recent times to try and achieve that goal, such as the recent appointments of Justices Dhanji, Yehia and Chen to the NSW Supreme Court.

Barristers are often employers. This is an opportunity to think broadly about your hiring options, to think outside the square, and consider what skills a diverse candidate might add to your barrister’s practice.

EC: You referred earlier in this discussion to the NSW Diversity Survey in 2018, which was published in the 2019 Autumn Bar News edition. As part of that survey, there were data collected about the ancestries of barristers which suggested that, as at 30 June 2018, there was a ‘significantly increased diversity among…young barristers’.3 That is, barristers born in 1978 or later. Have you witnessed such a change?

TW: Yes, the extent of increased cultural diversity has been most noticeable in the junior barristers. I think that it started to change around 10 years ago. We are now starting to see those junior barristers become more senior and shortly they’ll be able to apply for silk and contribute to the leadership of our profession. I’m expecting that, in another 10 years’ time, there will not only be a large number of diverse junior barristers but also diverse senior barristers such that the Bar as a whole will start to reflect the proportions in the Census data.

EC: In terms of where the Bar is at now, do you think there are still any barriers to entry or other structural or issues that may discourage people wanting to join the Bar or, once at the Bar, staying at the Bar?

TW: As I understand it, to get onto a good floor now, you frequently have to apply more than 18 months in advance. Often, you need to speak to people who have either gone through the experience themselves recently or talk to people who are on, for example, the readership committees to find out how to apply. If you’re from a family that has no connections to the legal profession, and that’s more likely to be the case if you’re from a cultural minority, that may present itself as a barrier to coming to the Bar. There can also be disadvantaged groups in the community who are from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds and simply don’t have good access to healthcare, social services and education. So, perhaps, from an even earlier starting point, those people might need access to programs to improve their ability to undertake tertiary education such that they can even be on a stepping-stone towards becoming a barrister.

In terms of people leaving the Bar, people leave the Bar for so many different reasons. There needs to be further studies to try and understand whether there are particular factors contributing to people leaving the Bar that result from their cultural background, and what can be done to try and assist them.

EC: Institutionally, there are various bodies that have made recommendations to address racial inequality at the Bar, such as the UK Bar Council in its November 2021 report, ‘Race at the Bar: A Snapshot Report’,4 and its November 2022 report, ‘Race at the Bar: Progress Report’.5 There are some interesting recommendations in those reports concerning access to the Bar, retention of barristers with an ethnic minority background, the progression of such barristers, and the culture of the Bar. That’s at an institutional level. What can each of us do to foster an inclusive and diverse legal profession?

TW: I think there are many things that we can all do individually and collectively to improve the inclusiveness and diversity of the profession. I’m a glass half-full type of person. I think that many people in the profession have already taken a number of steps that explain the improvements that we are seeing in the diversity of the junior Bar. Obviously, there is still work to be done, particularly in improving opportunities for Indigenous law students and colleagues.

So what can be done? Well, barristers are often employers. This is an opportunity to think broadly about your hiring options, to think outside the square, and consider what skills a diverse candidate might add to your barrister’s practice. Barristers also can have influence over briefing decisions – whether it is a colleague you are recommending who is more junior or senior to you. These are opportunities to support diversity. The same also applies to choosing new members, licensees or readers for your particular barrister’s floor.

There are also the decisions that we make on a day-to-day basis about how we are going to engage with our solicitors and clients, as well as our opponents. We need to be open-minded about the cultural differences that those we deal with on a day-to-day basis might have in comparison to ourselves, and have an awareness of our own unconscious biases. This can improve our exchanges with diverse individuals to ensure that they feel welcome in our legal community. There is a great CPD on unconscious bias that is available on the NSW Bar Association’s online portal.

I’ve also participated in diversity focussed mentoring programs. I have personally mentored a number of students, solicitors and junior barristers, encouraging them with their career goals and providing them with whatever support I can. Mentors and mentees can get a lot of value from formal and informal mentoring programs. The connections that you make can expand your reach into the legal community in ways that can be beneficial to yourself and others, and can often be unanticipated.

As a final thought, I also seek out opportunities to expose myself to the wealth of experiences that our Indigenous and migrant cultures offer to others in the community, whether by enjoying their meals, reading their books, or engaging with their stories as told through film, art or music. For me, this has been the entry point to a deeper, more nuanced and multi-faceted understanding of those who are different to myself that I have found to be of tremendous value in my professional as well as personal journey. BN

ENDNOTES

1 The Honourable Justice Hament Dhanji, ‘Cultural Diversity in the Law: it is not Revolution – but we are going to Occupy the Buildings’ (27 September 2022, Speech, The Law Society of New South Wales – Cultural Diversity Networking Event).

2 Brian Opeskin, ‘Dismantling the Diversity Deficit: Towards a More Inclusive Australian Judiciary’ in Gabrielle Appleby and Andrew Lynch (eds), The Judge, the Judiciary and the Court: Individual, Collegial and Institutional Judicial Dynamics in Australia (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

3 Ingmar Taylor SC and Chris Winslow, ‘Data on Diversity: the 2018 Survey’ (2019) Bar News (Autumn) 39, 39.

4 The UK Bar Council, ‘Race at the Bar: A Snapshot Report’ (November 2021).

5 The UK Bar Council, ‘Race at the Bar: A Progress Report’ (November 2022).